When Viktor Yushchenko was president, the acquisition of media assets was a kind of sport for the oligarchs, who viewed the mass media as convenient political leverage. However, the 2008 economic crisis shifted priorities and media projects turned into something like a suitcase without a handle for business conglomerates. First and foremost, this was true for print publications. In 2009, the first ones to face change were KP Media with the American publisher, Jed Sunden, as its main shareholder; and Glavred-Media controlled by tycoon Ihor Kolomoyskyi.

Sunden had closed down Novynar, a Ukrainian-language magazine that had survived just one year, back in summer 2008. In 2009, he sold Kyiv Post, an English-language weekly published since 1995, to the Pakistani-born steel tycoon, Mohammad Zahoor. In subsequent months, he got rid of a number of glossy magazines.

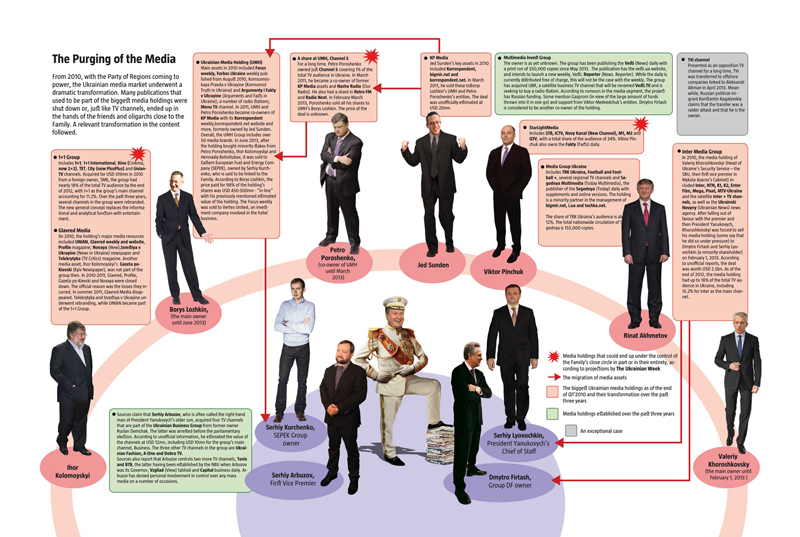

In spring 2011, the time came to sell the entire holding whose triune face was the Korrespondent weekly, as well as the bigmir.net and korrespondent.net websites. Petro Poroshenko and his Ukrainian Media Holding (UMH), run by media mogul Borys Lozhkin, became the new owners of KP Media. Poroshenko joined the deal as a minority shareholder of UMH.

READ ALSO: The Hidden is Becoming More Evident

Salary arrears began at Kolomoyskyi’s holding in 2009, even causing a strike at Glavred. But real changes came after Viktor Yanukovych became president. By the end of 2010, the holding stopped publishing the magazine and the Novaya (New) daily, as well as the print version of the Telekrytyka media publication. Summer 2011 saw the closure of Gazeta po-Kyivsky (Kyiv Newspaper), the brand under which a number of regional publications were produced, following a notorious scandal after the chief editor left what was one of the most popular dailies. Profile, another business magazine, went out of business. The online version of Telekrytyka and the Izvestiya v Ukrayine (News in Ukraine) newspaper left the holding and underwent rebranding. This was, in effect, the end of the holding.

Meanwhile, Kolomoyskyi maintained control of the UNIAN news agency. In early 2010, he bought a group of TV channels, including 1+1, TET, Kino (Films) and City.

Many saw a political motive behind this, particularly since most of Kolomoyskyi’s publications’ teams were critical of the Yanukovych regime. However, it turned out that the government hadn’t even started the media purge at that time. The fully-fledged campaign kicked off in 2013.

Inter Media Group with Inter, one of Ukraine’s most popular TV channels as its main channel, was the first to go. On February 1, news surfaced of the sale of Inter Media Group to gas and chemical tycoon Dmytro Firtash. Until then, Valeriy Khoroshkovskyi who was first vice premier in February-December 2012, owned the controlling stake. “I am unable to ensure the Group’s development under current circumstances, and these circumstances are my main motivation for the sale,” Khoroshkovskyi stated immediately after selling his company.

READ ALSO: The Press as a Mirror of National Consciousness

The leaked price of the deal left experts shocked: the holding supposedly cost the buyer an incredible USD 2.5bn. However, rumours in political circles have it, that it wasn’t the price that made Khoroshkovskyi accept the offer. The fact that Inter’s former owner has been abroad ever since and shows no intent of returning to Ukraine indirectly confirms this.

In April, it was the turn of TVi. The journalists of the cable TV channel, owned by a number of offshore companies, criticized the government so harshly, that many operators refused to broadcast TVi before the 2012 parliamentary election. In April, it suddenly changed hands: control went from the offshore companies controlled by Russian political migrant Konstantin Kagalovskiy to those ostensibly founded by an Odesa-born American businessman Alexander Altman. However, the public couldn’t help but notice the obscure role of Mykola Kniazhytskyi, an opposition MP and TVi’s former CEO, who backed the change, or the shady ownership structure of the “fair channel” (the authorized capital of the ultimate offshore company that owned TVi turned out to be a mere USD 1,000). Most journalists left the channel, while its reputation among the narrow but loyal audience suffered a devastating blow. Speculation as to who really stands behind the new owner still varies, but it is the Family that is mentioned most often.

The deal to sell UMH, a huge media holding, to the golden boy, 27-year old multimillionaire Serhiy Kurchenko, was relatively transparent. UMH is mostly comprised of various print publications, including the Korrespondent and Forbes-Ukraine business weeklies, the Komsomolskaya Pravda v Ukrayine (Komsomol Truth in Ukraine) daily newspaper, tabloids, as well as sports and cooking magazines. The holding also includes a number of radio stations and the most popular online portals.

If official data is to be believed, Kurchehnko acquired a slightly slimmed down holding: literally days before the deal was cut, UMH’s Borys Lozhkin sold the Focus weekly to investment group Vervex United controlled by Odesa businessmen Borys Kaufman and Oleksandr Hranovskyi, although they have never been involved in the media business before. There is logic behind this decision: when it was part of the holding, Focus was in the same niche as Korrespondent, and competition between them would develop more effectively if they had different owners.

In his comments shortly after the deal, Borys Lozhkin hinted that he had sold 98% of UMH for around USD 450mn. This is expensive, but the license for the Ukrainian version of the international Forbes, a vast distribution network and the advertisement market it dominates, may have swelled the price.

Lozhkin also made it clear that the deal was prepared hastily, in just a month, although he had previously denied rumours of the UMH sale on numerous occasions. Once more, the market started buzzing about an “offer he simply couldn’t refuse”.

Experts surveyed on our website assume that there will be no sudden changes in the editorial policy of Kurchenko’s publications, but gradual ones are inevitable. Some projects may close down. “Perhaps this was a kind of strategy, whereby Borys Lozhkin used mass publications like the Komsomol Truth to keep Focus and Korespondent intact,” says Oleksiy Mustafin, the Director General of the Mega TV Channel and one of the Inter Group’s top managers. “But it looks as though with time, it will become more and more difficult for them to stick to this strategy . It is quite possible that a demand (by Kurchenko – Ed.) to fold everything down prevailed here, or the magazine covers were simply irritating because far more people looked at them rather than the articles.”

So, some media moguls have already lost their resources. Meanwhile, new media empires are on the rise. One feature they all share is secret owners. This cannot but fuel suspicion of government support in the establishment of the new informal media groups. Experts unanimously claim that the Family is thus establishing its propaganda arsenal.

READ ALSO: Endurance Test

Unknown people have recently bought a number of TV channels and established several new newspapers. This is not easy to do at a time when most big businessmen are cash-strapped and do not expect investments. Someone bought Tonis, a TV channel that was on the brink of bankruptcy. Someone also bought four channels of the Business Group. There is an interesting story behind this: the group’s owner, Ruslan Demchak, was detained on charges of the misappropriation of state funds shortly before he was going to run against Hryhoriy Kaletnyk, a pro-government businessman and the father of the current First Vice Speaker of the VR, in the last parliamentary election. Demchak was released in February, and signed the deal to sell the channels shortly thereafter for an undisclosed sum.

Initially, the deal was attributed to Kaletnyk father and son. Later, the prevailing version was that the buyer was either Yanukovych’s older son Oleksandr or Serhiy Arbuzov. The latter is also rumoured to have launched the Vzgliad (View) tabloid, the Capital business daily, and BTB, a TV channel set up by the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) back when Arbuzov was its governor. Some sources claim that BTB has already invested up to UAH 300mn into development.

The Family is not the only rising media mogul. Ex-chief editor of Akhmetov’s Segodnya (Today) daily newspaper, Ihor Huzhva, recently headed a new media holding based on the Vesti (News) daily newspaper distributed for free in big cities (see The Purging of the Media for more details). The group’s sources of funding are a secret. According to Huzhva, it operates on “borrowed funds” and the free daily should start bringing profits within four years, mainly due to advertising. Media experts see a different purpose. “As a non-market but quality product, Huzhva’s Vesti may well oust Segodnya and Fakty from the market,” Natalia Lyhachova, chief editor of Telekrytyka, notes.

Rumour has it that Dmytro Firtash may be one of the new media group’s financial donors, while the media talk of Russia, more specifically Gazprom. “Nobody in Ukraine has a spare few million dollars a year today to support a newspaper distributed for free, but it’s not a problem for our neighbours,” an experienced PR expert shares his assumptions. “The Kremlin has probably not yet decided whom it will support in the 2015 presidential election but it is already preparing propaganda instruments.

READ ALSO: How Information Society Can Drive Democratic Change in Ukraine

The owners of media holdings who have so far managed to protect their assets from the appetites of Russia and the Family must feel very insecure in this situation. The biggest ones include Petro Poroshenko with his Channel 5, Ihor Kolomoyskyi with the 1+1 Group, Viktor Pinchuk whose group of STB, ICTV and Novy Kanal (New Channel) accounts for nearly 1/3 of the total viewing audience, and Rinat Akhmetov who owns Segodnya multimedia group and Ukraine TV Group, which recently merged into a single holding.

Naturally, the relatively weakest players will probably fall prey to the ambitions of the new “media moguls first”. “The less powerful the asset, the greater the doubt that it remains in the hands of the current owner,” Oleksiy Mustafin explains. “First, all the rubbish will be bought (fortunately, the buyers don’t know much about the Ukrainian media market), followed by small assets.”

However, the reality is more complex than this. Since last year, Kolomoyskyi’s group has been in a long-drawn-out war for the advertising market against the united front of Pinchuk, Akhmetov and Firtash, making it financially vulnerable. Meanwhile, Kolomoyskyi’s interests are backed by other businesses, primarily banking, and links to the establishment in Israel and the US. Similarly strong is Pinchuk’s position in the West. Akhmetov has enough authority within the country.

Still, everything comes to an end at some point. “I think many are frozen in anticipation to see the fate of UMH in the television segment,” Natalia Lyhachova concludes. “For now, Kolomoyskyi, Akhmetov and Pinchuk still have their holdings. Given the circumstances, the Family trusts none of them as much as it trusts itself. Everyone can thus draw their own conclusions… But the monopoly of one group poses the threat of the establishment of total media purge regime and a return to the times of “party hierarchy and party literature.”