Every year, thousands of Ukrainians travel abroad as migrant workers in search of better jobs. Often, the families they leave behind are tested to destruction. Many families have been ruined for the chance to buy an apartment with euros, dollars or rubles earned abroad, and children often pay the highest price for their parents’ high-class gifts: being left all alone during the critical stages of childhood.

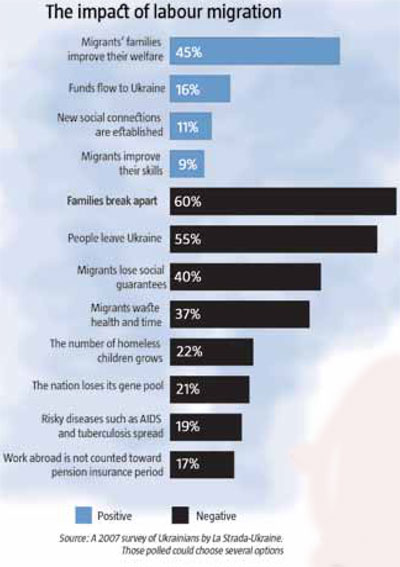

According to La Strada Ukraine, an international centre for women’s rights, labour migration leads to family break-up in 60% of all cases throughout Ukraine, with 73% in Western Ukraine, and 58% and 59% in Eastern and Central Ukraine respectively.

WORLDS APART

“Her way is to the Warsaw suburbs, his is to the concrete of Moscow. Very soon, their love on the phone is bound to die,” sings BoomBox, a popular Ukrainian indie funk band. Odesa-born Halyna, 28, admits that she cannot hold back her tears whenever she hears the song. She is divorcing her husband who has been working in St. Petersburg for several years now. “Dmytro got sacked when the crisis broke out in 2008,” she recalls. “I still had my job but how can a family of two live on an average monthly salary? We spent it all on the rent and food.” Dmytro could not find a decent job as a software developer in Odesa for a year and his occasional freelance paychecks hardly helped. “I began to shout at him,” Halyna admits. “Once I called him a loser. It was difficult to forget what I was used to and realize that I couldn’t buy make up or grab a cab a few times a month. And it was scary to see how my husband was losing his confidence and realize that I no longer believed in him, too.”

When Dmytro’s friends offered him a job in Russia, he did not hesitate. “I supported his decision,” Halyna says. “He rented a small room in St. Petersburg to save more money.” Halyna refused to leave the city where her friends and elderly parents lived. “Who needed me there, yet another designer? What would I do there – clean floors in a museum?” she wonders.

Initially, Halyna and Dmytro visited each other at least once a month – plane tickets were expensive and a train ride took 24 hours. Eventually, they saw each other only “once in a while” and chatted less online. “I noticed that one woman from St. Petersburg was posting a lot of songs and messages on his social network page,” Halyna recalls. “Jokingly, I asked him, ‘Are you sleeping with her?’ After a long pause, he said ‘Yes.’”

Dmytro apologized many times but his wife no longer trusts him. There is no sense in saving the relationship, she says. “I don’t see any prospects for us. He is making a career there and is not planning to return ‘so far.’ I have my life here, at home.” The couple does not have children—often a deciding factor in keeping parents together despite such conflicts.

Many Ukrainian women who work abroad also find new husbands there. “When the post-soviet migration surge began, it was mostly men who went to work abroad,” notes Alisa Tolstokorova, an expert in gender issues and problems of migration in transnational families. “Lately, however, more and more women go abroad leaving their husbands and children at home.” Adjusting to a new environment and lifestyle and getting used to a different social status – usually one that is lower than back home – is difficult regardless of gender. Yet, women, accounting for 33% of all Ukrainian migrant workers, are much more vulnerable to the stress caused by these changes, reports International Organization for Migration (IOM).

ABANDONED CHILDREN

“Isolation from one’s family can have a serious psychological impact because it makes one feel unstable, abandoned, sad, lonely and emotionally detached all the time. This aggravates the culture shock that female migrants experience,” Alisa Tolstokorova notes.

A survey of Ukrainian labour migrants conducted by the Oleksandr Yaremenko Institute for Sociological Research shows that, whenever one or both parents leave to work abroad, 44% of children stay home with their mothers, 35% stay with grandmothers, 14% stay with their fathers, 14% and 12% stay with older sisters and brothers respectively, while 10% and 5% stay with their grandfathers and aunts or uncles respectively. Many children, however, are left without any care from their parents or the state.

“My friend’s wife went to Italy,” Kyiv-born Olya says. “She left two children with him. One day, he posed for a picture with a TV anchor. His younger son saw the picture and asked him ‘Is this my mom?’” Eventually, the family broke apart. The parents divorced but the children stayed with the husband. Often, female migrant workers lose their status of both wife and mother.

“Female migrants are often forced to accept a situation where their children are more attached to strangers despite their frequent trips home, phone calls, letters and videos of their life abroad,” Alisa Tolstokorova explains. “Sometimes, kids left with someone who takes care of them start treating them as their real mothers and forget their biological ones.” They have a hard time understanding their parents’ financial difficulties and motivation for leaving, and they feel betrayed, abandoned and sometimes even refuse to stay in touch with them. When children do not see their fathers and mothers for long periods of time, it has a negative effect on their worldview.

When parents move abroad, the child’s surroundings, habits and values change, sociologist Inna Shvab writes in her analytical report titled “The Problems of Labour Migrants’ Children.” Before parents migrate, children care more about their place in society, the town or city the family lives in, education in a good school and good grades. After migration, they switch to clothes, a glamorous lifestyle and traveling abroad. Good grades often plummet immediately as a result of the lack of parental supervision.

Of course, not all people leave the country alone. Some couples move together, especially to work as housekeepers and gardeners. Labour migrants say that this is virtually the only way to save the family. However, this sort of employment does not offer the opportunity to take children along, so most parents leave them with relatives or neighbours, while teenagers often end up alone, with no supervision from adults. Some parents, especially those who work in construction, take their young children. They live with their parents and do not go to school, which does not bother the parents. “We will buy their school diploma when we come back, and our children will also work abroad just like we do when they grow up, so why do they need an education?” a migrant from Transcarpathia says.

According to the IOM, 56% of Ukrainians go abroad for better salaries and quality of life rather than because of unemployment. Yet most fail to foresee the devastating effect that their absence can have on their families and children.

Sociologists say that labour migration has been one the factors that affected the way Ukrainians treat their families over the past few years. Every fifth baby is now born out of wedlock, almost twice as high as in the early years of Ukraine’s independence. Also, women are willing to have babies at an older age now and more and more families have just one child.