At year-end 2012, Kyiv saw numerous billboards advertising a mysterious newspaper that nobody could find. It continues to be published in a strange shadowy regime. This was symbolic: non-existent media is promoted on a massive scale while that which exists is totally ignored, as if it does not exist. A double phantom as the perfect image of the state of the Ukrainian press.

There is no mystery behind the phantom newspaper: a media holding is currently being established. It will soon own a daily tabloid with a Sunday supplement, a business daily, a website, a TV channel, and probably something else, all of them in Russian. Sources inside the potentially powerful entity claim that the funding is linked to First Vice Premier, Serhiy Arbuzov. This is hardly surprising: as the future (sooner or later – the first option seeming more likely) premier and promoter of the Family’s interests ascends to power, he thinks that he needs a mouthpiece of his own. The question is what it will be: the symbolic trappings of power and arrogance; a zoo or a slave theatre, or a potential tool of media influence? No matter what, it will definitely not be a business as a source of income, let alone something that serves either society or the press, as has been the case for hundreds of years west of the homeland of the Soviet Truth (Pravda) newspaper.

READ ALSO: Bad Manners

PHYSICIAN, HEAL THYSELF

“Why is the career of a journalist so short in Ukraine?” is the question – and observation –recently discussed on the net. Today, there are very few star journalists around who were the faces of the press and television 10-15 years ago. The rest switched to politics or business, or became discouraged and turned inward, as if this is some kind of hazardous industry. This is not the case in other countries: It takes Western journalists years to gain a name, reputation and circle of loyal consumers and fans which they don’t lose, unless it’s to a scandal. Being a reporter, columnist or political TV show host are all long-term careers. The online discussion led to a somewhat accurate explanation. The more professional a journalist is in Ukraine, the more internal pressure he/she faces as the practical effect of his/her publications are close to zero. They do not stop abuse and corruption, criminals are not punished, problems are not solved, and society does not become aware of them. Instead, it often accuses journalists of being paid by someone to say what the latter wants. Yet, deep inside, even the most cynical journalists still need some firm principles they can believe in to stay in good professional shape. Once these principles are threatened, they are followed by burnout.

“Why is the career of a journalist so short in Ukraine?” is the question – and observation –recently discussed on the net. Today, there are very few star journalists around who were the faces of the press and television 10-15 years ago. The rest switched to politics or business, or became discouraged and turned inward, as if this is some kind of hazardous industry. This is not the case in other countries: It takes Western journalists years to gain a name, reputation and circle of loyal consumers and fans which they don’t lose, unless it’s to a scandal. Being a reporter, columnist or political TV show host are all long-term careers. The online discussion led to a somewhat accurate explanation. The more professional a journalist is in Ukraine, the more internal pressure he/she faces as the practical effect of his/her publications are close to zero. They do not stop abuse and corruption, criminals are not punished, problems are not solved, and society does not become aware of them. Instead, it often accuses journalists of being paid by someone to say what the latter wants. Yet, deep inside, even the most cynical journalists still need some firm principles they can believe in to stay in good professional shape. Once these principles are threatened, they are followed by burnout.

READ ALSO: How Information Society Can Drive Democratic Change in Ukraine

In addition to all the flaws that Ukrainian society has failed to overcome in the two decades of independence, it is also to blame for the inefficiency of the press as a platform for the discussion of urgent issues. It has little trust and social capital, and is stuck in obsolete mythology – be it patriotic or Soviet. The government does not provide efficient communication and feedback because it is busy with completely different tasks: servicing those in power. Meanwhile, the media are equally unprepared to fulfill their actual functions, among other things, because of their burdensome legacy.

The work of Ukrainian media is not based on either business competition, news or ideas. This comes partly from Ukraine’s economy, in which monopolists have total control over the market and wipe out what is supposed to be a competitive environment. For this, they often use external resources coming from the media owners’ other businesses in the best-case scenario, or else from abroad, and spread the necessary materials that play into the hands of those who support them. Thus, they turn into propaganda tools.

THE CARNAVAL GOES ON…

This vicious circle will remain unbroken as long as the press is treated as a promoter of ideas or opinions that are convenient for the government or media owners. Most Ukrainian journalists today qualify professionally as the descendants of those working on Soviet newspapers, magazines, radio and TV. They were called “the party soldiers”. Indeed, all press in the USSR, without exception, reported to the “agitation and propaganda department” of a relevant party authority and fulfilled its instructions. The entire collective experience of the party press is a relentless mockery of sound reason, dignity and truth. A comparison of academic programs at journalism faculties in universities today with those from 25 years ago shows how mentally similar they are. The same thing applies to those who call the tune: the smart suits of Ukraine’s current elites still often hide the uniforms of one-time party and Komsomol directors. They see the mass media as a tool of influence and nothing more.

Propaganda, or its softer version, PR, is the key word to define the objectives of the TV channels, radio stations, newspapers and online resources controlled by oligarchs, the government and to a lesser extent, the opposition. Some may pretend to sabotage instructions, continue with creative endeavours, simulate the style and approaches of the real mass media, demonstrate a balance of opinions, and sometimes even fool the owners as they publish hidden advertisements, yet they are ultimately forced to fulfill the strategic tasks they are paid for. The few independent media in Ukraine are a minority and do not establish the rules.

The other side of the barricades, i.e. consumers, are largely inert and skeptical. The level of Ukrainians’ trust in the press is plummeting, as proved by sociological surveys. Part of the audience just accepts the tabloids without any analysis. Those who process information critically, always doubt the media, wondering who needs and orders the material they contain. This is true for everyone, from those in power to the opposition, intellectuals, representatives of liberal professions and students. Any forum discussing new publications confirms this. Equipped with their pragmatic approach to the “freedom of speech”, politicians, media owners and journalists have entrenched the Soviet understanding of what mass media should do in society. Many Ukrainians also see the Fourth Estate as a pure form of propaganda or tabloids.

READ ALSO: Ukraine’s Last Independent Magazines Threatened

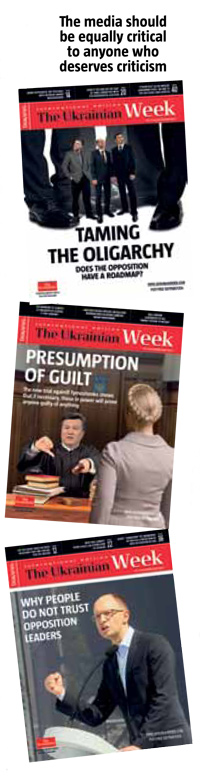

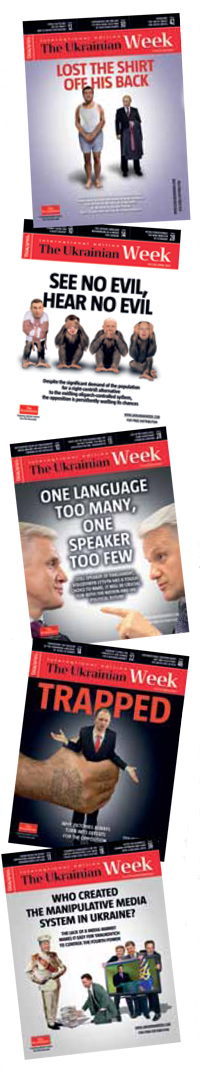

We have experienced this many times. Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week has always tried to be the Fourth Estate and called things by their names. We published critical materials on current developments and figures, covering Yushchenko and Tymoshenko when they were in power; representatives of the Yanukovych regime, current opposition leaders, oligarchs, and civil activists aspiring to be opinion leaders. Those criticized and their supporters have yet to look at the essence of the criticism, preferring to accuse the publication of malicious attacks against those it does not like.

Quite a few pocket media on the local underdeveloped market have made efforts and used resources for the creation of idols, who have played or will play a destructive role in Ukrainian politics. Some of the best-known media-promoted idols include the “most discreet politician”, Oleksandr Moroz; the “European-oriented entrepreneur” Petro Poroshenko; “Ukrainian patriot and great reformer” Viktor Yushchenko, to name but a few. Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week has tried more than once to dispel these myths to prevent Ukrainian society from making yet another mistake by relying on such people. Before the 2010 presidential election, one of our issues had a cartoon of Yushchenko on the cover with a slogan that said “The Killer of Faith”. At that time, some of his supporters, including many of our readers, accused us of cooperation with the Party of Regions; others speculated about our links to Tymoshenko. Some called on our readership not to purchase the publication calling it anti-Ukrainian. History soon put everything into perspective.

It appears that history is repeating itself. Just like those in power, opposition elites do not understand what the real press is supposed to do. They only seem to be interested in the media as a platform for paid advertising or free promotion in independent publications. During and after the parliamentary election, we criticized the current regime, also pointed out the mistakes of opposition leaders, including Arseniy Yatseniuk, Vitali Klitschko, Oleksandr Turchynov, Andriy Kozhemiakin and others, hoping that constructive criticism will push them to make adequate conclusions and decisions that will benefit the Ukrainian majority. Instead, they claimed that an article criticizing Yatseniuk was ordered by Klitschko, one criticizing Klitschko – by Yatseniuk, and on Tiahnybok – by either one or the other. When asked for an interview once (Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week has been trying to arrange this for some time now, without success), Yatseniuk refused point blank because “you (Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week – Ed.) are working for the Party of Regions”. Apparently, in the eyes of Yatseniuk, whoever dares to point out his shortcomings as a Batkivshchyna leader is almost certainly paid by the government. This view is also held by most other opposition politicians. “You don’t inspire us (the opposition – Ed.),” Batkivshchyna’s MP Lesia Orobets told our reporter during PACE’s January session in Strasbourg. Would we look more constructive in their eyes and invigorate the opposition to heroic acts if we wrote of “Yatseniuk as the father of Fatherland-Batkivshchyna” in every issue? Or forgot to mention that Orobets, along with her party colleague, Serhiy Sobolev, did not vote in favour of acknowledging Azerbaijani activists as political prisoners at the latest PACE session, even though a positive decision on it would have boosted Tymoshenko’s and Lutsenko’s chances of getting political prisoner status at the next PACE session in April.

It appears that history is repeating itself. Just like those in power, opposition elites do not understand what the real press is supposed to do. They only seem to be interested in the media as a platform for paid advertising or free promotion in independent publications. During and after the parliamentary election, we criticized the current regime, also pointed out the mistakes of opposition leaders, including Arseniy Yatseniuk, Vitali Klitschko, Oleksandr Turchynov, Andriy Kozhemiakin and others, hoping that constructive criticism will push them to make adequate conclusions and decisions that will benefit the Ukrainian majority. Instead, they claimed that an article criticizing Yatseniuk was ordered by Klitschko, one criticizing Klitschko – by Yatseniuk, and on Tiahnybok – by either one or the other. When asked for an interview once (Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week has been trying to arrange this for some time now, without success), Yatseniuk refused point blank because “you (Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week – Ed.) are working for the Party of Regions”. Apparently, in the eyes of Yatseniuk, whoever dares to point out his shortcomings as a Batkivshchyna leader is almost certainly paid by the government. This view is also held by most other opposition politicians. “You don’t inspire us (the opposition – Ed.),” Batkivshchyna’s MP Lesia Orobets told our reporter during PACE’s January session in Strasbourg. Would we look more constructive in their eyes and invigorate the opposition to heroic acts if we wrote of “Yatseniuk as the father of Fatherland-Batkivshchyna” in every issue? Or forgot to mention that Orobets, along with her party colleague, Serhiy Sobolev, did not vote in favour of acknowledging Azerbaijani activists as political prisoners at the latest PACE session, even though a positive decision on it would have boosted Tymoshenko’s and Lutsenko’s chances of getting political prisoner status at the next PACE session in April.

READ ALSO: Disgracing a Country

The task of the mass media as the Fourth Estate is to push politicians and officials to solving social problems and focus on issues that are vital to the state. It is then up to legislators, the executive branch and NGOs to take the necessary decisions. The problem, however, is that a large part of civil society views the function of the media in the traditional Soviet way. For instance, NGOs interpreted Ukrayinsky Tyzhden/The Ukrainian Week’s article on the decline of NGOs in Ukraine (see Issue 6(29) of April, 2012) as a paid one, although who could have ordered it? Who needs to ruin their reputation, given that none of them can really affect crucial decision-making, or prevent decisions that damage the nation’s interests? Ultimately, none of the NGOs we mentioned acknowledged that today’s NGOs have failed to grow into a fully-fledged basis for civil society – a critical factor that launched the renewal of post-communist countries in the early 1990s – those that are now EU member-states. Instead, the Institute of World Policy, the International Centre for Policy Studies and a number of other NGOs offered the number of events they organized as a counterargument to the criticism. However, what matters is the quality, not the quantity, while hardly any of the discussions, investigations or initiatives by Ukrainian NGOs have nudged the government or legislators to taking any specific decisions. The smoking ban in public places, lobbied by one NGO and eventually passed by parliament, is not really a good example: it ended with yet another corruption-spurring tax on cafes and restaurants, i.e. SMEs. While seeking the status of influential players, NGOs have still not noticed the real challenges that are right in front of them and the nation: an economy monopolized by oligarchic groups; increasing Russian influence; the ousting of independent Ukrainian-language media from the market by big media holdings, among others; the domination of Russian-language media and books on the market, and so on.

If society does not see the mass media as a Fourth Estate, why would the government? As a result, there has been no adequate reaction to journalists’ investigations of blatant scams for at least the last three years that would end in a prosecutor’s inquiry or the firing of a civil servant, which is common practice in civilized countries. Society, be it a viewer or reader, doesn’t even demand this, and where there is no demand, media owners do not feel obliged to invest in the costliest form of0 journalism; investigation, coverage by reporters or a proper analysis. Rewriting ready-made news from the Internet with pictures added here and there is a much cheaper option. Hence the conclusion: Ukrainian journalism is inevitably degrading, pulling down the entire media market.

READ ALSO: Keep Pushing for Change

… BUT THE DOGS SHOULD CONTINUE TO BARK

“Journalism is the watchdog of democracy” says a well-known slogan. Indeed, the press is supposed to ring alarm bells, make a noise, spoil moods and raise inconvenient issues. Otherwise, it is only pretending to be mass media. It has to keep barking, even if it risks sounding inadequate at times and has to pay for the risks.

So, what can a journalist, who is aware of this function, do when his efforts always prove insufficient or futile? The first priority is to raise his/her own professional standards and keep working on the knowledge and analysis of the issue he/she is covering. The more professional the publication, the more unquestionable and exclusive the facts it uses. The more qualified the experts and deeper the analysis, the harder it is for society to turn a blind eye. Eventually, good journalism will be entrenched in collective consciousness.

The second priority is to believe that society needs objective information and well-grounded assessments, while weariness and burnout means capitulation – a wasted chance to change the country and the life of future generations – to all intents and purposes, treason. The media still play their healing role even in underdeveloped democracies. They tell smart, socially proactive and responsible people that there is still an undistorted system of coordinates, help them to develop their own perception of what is going on, and contribute to uniting the existing fragmented civil society. And sometimes they succeed: talking into the audience directly is often more encouraging than sales figures or viewing statistics online. The best compliment for a journalist is someone saying “You helped me to express what’s on my mind.”