Odesa in the 1920s… In this bustling Ukrainian port city, the artistic scene is flourishing. The All-Ukrainian Photo-Cinema Administration (VUFKU) has emerged as a major film studio where numerous Ukrainian artists and intellectuals are bringing their cinematic dreams to life. Energised by contemporary ideas, they are crafting and realising their creative visions. This is where Ukrainian cinema began to take root.

Among these young artists was Oleksandr Dovzhenko, who would later become a renowned director known for iconic films like Zvenyhora, Arsenal, and Earth. He also wrote numerous screenplays, short stories, and dramas, earning his place in cinema history as a pioneer of poetic cinema. Today marks the 130th anniversary of his birth.

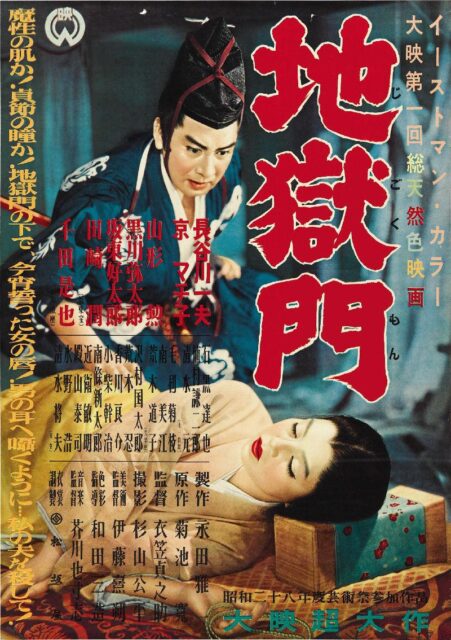

Dovzhenko’s work is studied in film academies around the world. Film critic and director Arthur Knight, in his book The Liveliest Art: A Panoramic History of the Movies, notes that Dovzhenko’s Earth inspired Japanese director Teinosuke Kinugasa to create Gate of Hell, which went on to win an award at the 7th Cannes Film Festival.

Photo: Teinosuke Kinugasa, “Gate of Hell”

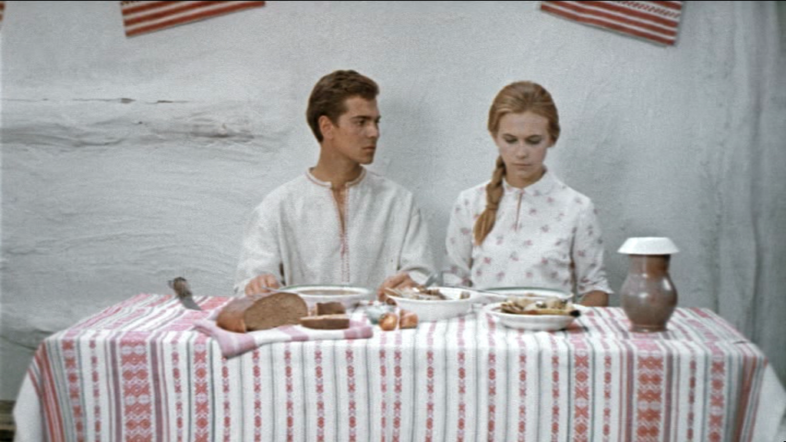

Dovzhenko’s work introduced the world to the poetry of cinema. But what does that really mean? His films are a manifesto of the interplay between nature and progress, the magic of existence, and a vivid celebration of nature’s beauty—like the apple orchard in Earth, a sort of “Ukrainian Eden.” These silent films spoke not with words but with symbols, creating a kind of visual poetry. The viewer’s role is to follow the emotional conflicts of the characters and navigate the labyrinth of the director’s metaphors.

Photo: a scene from Dovzhenko’s ‘Earth’

Cinema, unlike theatre or painting, is a unique art form—it doesn’t let you experience events live as they happen. Yet, Dovzhenko’s films, particularly Zvenyhora, Arsenal, and Earth, transcend the coldness of the camera lens, powerfully conveying the intense emotions of characters poised between past and future, life and death, good and evil, light and darkness, truth and deception.

Dovzhenko’s film Earth also became iconic for a scene in which a young woman, upon hearing of her lover’s death, tears off her clothes in a surge of raw emotion and grief. This was the first “nude” scene in Soviet cinema. In 1958, leading film scholars and critics at the Brussels World’s Fair recognised Earth as one of the 12 greatest films in history.

British film critic Chris Fujiwara, in his article The Neglected Genius: Oleksandr Dovzhenko at MFA, emphasised the avant-garde nature of Dovzhenko’s films, the complexity of his editing, and his profound love for aesthetics, which captured the enchantment and joy found in the natural world. Dovzhenko had an unparalleled ability to reveal the beauty in all living things. The reference to his “neglect” comes from the fact that Dovzhenko’s work remains insufficiently studied, leaving many to wonder why his films are still considered essential viewing.

A well-respected director?

How was this artist honoured in his homeland during his international success? Imagining laurels and numerous awards? You’d be mistaken. The film Earth was harshly criticised for its insufficient condemnation of so-called “kulaks” (simply wealthy peasants whom the Soviet authorities considered class enemies and ordered to be eradicated) and for being too obscure for the masses. Ultimately, the film was banned in Ukraine (then the Ukrainian SSR), Dovzhenko’s homeland. For the world, he remained a Russian director for a long time.

Dovzhenko’s Ukraine

Oleksandr Dovzhenko was part of a generation denied the right to embrace their Ukrainian identity. His film novella Ukraine in Flames, directed by Yulia Solntseva, where he boldly exposed the deep scars left on Ukraine by World War II, was condemned by the Kremlin elite for its so-called “bourgeois nationalism.” Who knows—perhaps the international acclaim for his earlier works spared him from the fate that befell hundreds of his colleagues, leading only to his exile in Moscow rather than execution.

In his films and writings, Dovzhenko, perhaps without fully realising it, restored something stolen from his fellow Ukrainians—their land and ancestral heritage. He never referred to Ukraine as Russia, nor did he ever call himself Russian. Oleksandr Dovzhenko made Ukrainian films about Ukrainians.

Photo: A still from “Ukraine in Flames”, a movie based on Dovzhenko’s novel and directed by Yulia Solntseva.

The idea of Ukraine

As early as the Baroque era, the idea of Ukraine—a land steeped in history—began to take form. Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s film Zvenyhora appears to carry forward the legacy of The History of the Rus’, an anonymous late Baroque work that portrayed Ukrainian lands as a crossroads of cultures, all of which Ukrainians share a deep ancestral connection. In Dovzhenko’s films, Ukraine transcends time, becoming chronologically all-encompassing. He explores the distant past through a profound archaic lens, reflects on the present, and envisions a future for Ukraine. This cinematic synthesis can be seen as his personal myth.

Photo: A snapshot from “Zvenyhora”.

The way Dovzhenko weaves time into his films reveals a duality. On one hand, it reflects a modernist trait that completely deconstructs traditional notions of time and space. On the other, it’s a historical carnival populated by Scythian tribes, rebels, and his contemporaries. Despite being denied the right to express national self-awareness, Dovzhenko intuitively grasped the pulse of his people and their unjust suffering. His close friend, poet Mykola Bazhan, reflected on Dovzhenko’s deep connection to the soul of his nation in his memoirs:

“Sashko had an absolutely unerring sense of nationality. With the lightest intonation, the subtlest modulation, he never missed a note, singing his favourite song from childhood—the beggar’s cant from Chernihiv about truth and injustice. ‘Oh, there is no truth in the world…’—as wandering beggars had sung for at least a hundred years, sitting on the porch of the ancient Dovzhenko family home, which belonged to the Chumaks.”

Modernity and archaic roots

In his Memoirs, Mykola Bazhan reflected on the deep roots of Dovzhenko’s soul, highlighting how Dovzhenko perceived the village for what it truly was—neither through the lens of romanticised idyll nor with disdain. This understanding was largely shaped by Dovzhenko’s deeply Ukrainian origins. Growing up in the tiny hamlet of Vyunyshche near Sosnytsia in Chernihiv Oblast, he developed an intimate connection with village life and its raw, untamed, almost primordial depth. The villagers in his works are portrayed as complex individuals grappling with crucial choices, reflecting, doubting, and seeking stability. Their rich character development and emotional depth reveal a modernist approach that Dovzhenko employed to depict the mythopoetic rural landscape.

“Dovzhenko’s Zvenyhora and Earth stem from there—from those Chernihiv ravines, from the land soaked with the sweat of fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers, whose essence, and that of the people who live on it, the artist captured with such profound insight”, wrote Mykola Bazhan in his Memoirs.

Whether it was the pull of endless memories or the call of his heritage, Dovzhenko could never sever his connection to his Ukrainian roots. In his film narrative Enchanting Desna, he explores the perpetual cycle of memories within his soul.

Photo: A still from Dovzhenko’s “Enchanting Desna”

“What stirs them? (memories – ed.) Long years of separation from the land of one’s forefathers, or perhaps it’s simply the nature of things—that there comes a time when the tales and prayers learned in the distant past of childhood resurface, filling every corner of one’s memory, no matter where life has taken them”.

Dovzhenko — was he a propagandist?

If the era in which Dovzhenko lived had a hashtag, it would be #fear. Fear made people live in a constant state of dread, turning friends into enemies. In his Diary Entries, Dovzhenko wrote: “Reality became scarier than even the most tasteless imagination.” So, was Dovzhenko a sincere communist? And how does that align with the concept of fear?

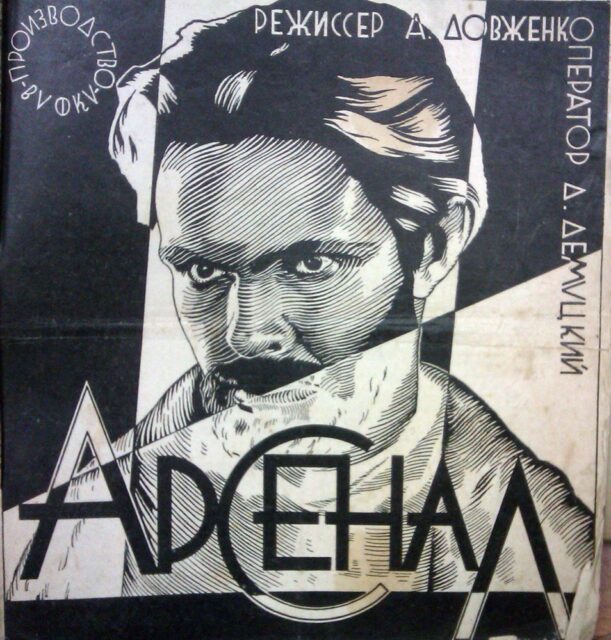

The answer might be this: fear destroys genuine convictions, reducing a person to a manipulated, almost animalistic state and breaking them psychologically. Where fear reigns, there is only adaptation and constant caution. Of course, giving in to fear is also a choice. Changing allegiances is a personal decision. Dovzhenko started as a soldier in the Ukrainian National Republic, participating in the suppression of the Bolshevik uprising at the Arsenal Factory in 1918. Yet, in 1928, he directed a film about these events, but from the perspective of the opposing side. To judge such actions, one must first understand the fear that permeated that time. Without this context, judgment is shallow. Thousands of Ukrainian artists were tortured or killed during the Soviet repressions of the 1930s. Cultural figures were forced into a paradigm of “survive or perish.” Dovzhenko, in his diaries, wrote about interacting with Stalin, the orchestrator of mass crimes against Ukrainians—repressions, the Holodomor, and deportations.

Photo: “Arsenal” poster.

“I regret that I didn’t approach Stalin and tell him that everything was completely different. Now, what can I say to him? What can I hope for when such a tremendous burden of international struggles to create a new, rational world rests on his enormous shoulders?”.

Were these expressions of respect genuine? We may never have a definitive answer. Perhaps even Dovzhenko himself might not have known. Sometimes, our soul feels like a well with an unreachable bottom. However, one thing is clear: Dovzhenko’s career and life were deeply influenced by the directives of the leadership.

Multiple meanings

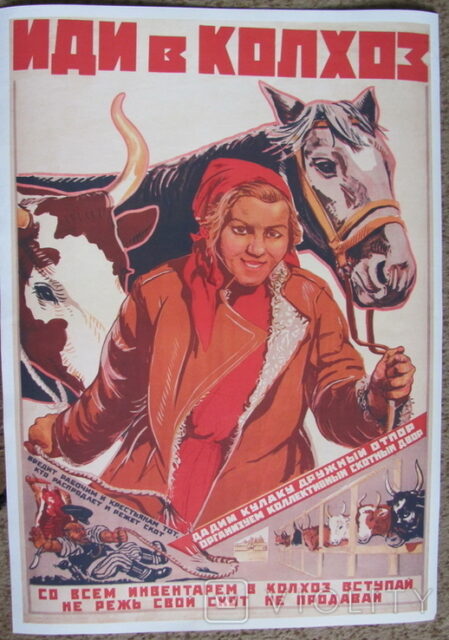

Dovzhenko’s films operate on multiple levels. On one hand, they celebrate the land and its impact on people’s lives, evoking a hymn to nature and vitality. On the other hand, they reflect the influence of socialist realism—a tool for promoting ‘collectivisation’ and industrialisation. In Earth, for example, the glorification of “collectivisation” masks the real effect: the suppression of the Ukrainian village’s autonomy and its resistance.

Are Earth, along with other seminal works like Zvenyhora and Arsenal, propagandistic? Likely so. According to socialist realism, these films were designed to portray a triumph over the natural and traditional. This pseudo-collective vision stifled national identity. Yet, this does not diminish their importance; without such films, Ukrainian cinema would lack its historical foundation, models, and traditions.

Photo: Soviet poster promoting the so-called ‘collectivisation’

The Dovzhenko Centre

Ukrainian culture celebrates Dovzhenko as a central figure in its cinematic history. The state film studio in Kyiv bears his name, where countless films were produced.

Today, his legacy is preserved at the Dovzhenko Centre, the largest Ukrainian film archive. The Centre has restored many of his films, which are now enhanced with modern musical scores by the Ukrainian band DakhaBrakha .

“‘How I suffered and cursed the administration, which devoured my nerves, my soul, all my strength with its worthlessness’—this quote from Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s Autobiography reveals much about his life and the evolution of Ukrainian culture. Creativity demands freedom. Without it, an artist is like a plant wilting without essential nourishment. How can one live and create when identifying with one’s people is considered a crime and everything around is consumed by propaganda? This encapsulates Dovzhenko’s entire story.”