Ukraine-Lithuania: Timofei Dokshizer

The Kaunas Jazz Festival. The jazz trumpet virtuoso Arturo Sandoval addresses an enthusiastic crowd: “Who among you know of the great trumpet player Timofei Dokshizer, who died in Vilnius?” (Dokshizer was a legendary Ukrainian-born trumpeter who lived in Lithuania, and who was known from childhood on for his unforgettable performance of the Neapolitan Dance in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.)

The deathly silence was understandable, for no one came to Sandoval’s concert to discover unknown locals. “Timofei Dokshizer was an exceptional trumpeter and teacher. I dedicate this composition to him. Is his wife in the hall?” A small, modest woman – Dokshizer’s widow – stands up. “Thank you,” says Sandoval.

RELATED ARTICLE: Olena Chekan: re-thinking Ukraine through art and journalism

And here I think to myself. Memory comes from somewhere else. Memory comes from the Other. We only think that we preserve the memory of a place, when in truth it comes from elsewhere to preserve us. We need the sensation of being created, founded, and proclaimed to the world, when in fact it is others who bear witness about us to the world. The memory that saves us from non-being comes from elsewhere. Memory does not live here. Memory lives elsewhere.

Lithuania-Israel: Vyacheslav Ganelin

Vyacheslav Ganelin is a Lithuanian and Israeli composer, jazz pianist, and mentor. His is an entire school of jazz music and sensitivity that we can describe as the Vilnius School of Jazz. One of the fathers of Lithuanian free jazz, Ganelin has engraved his name as a major Lithuanian film composer as well.

The music Ganelin wrote for the Lithuanian film The Devil’s Bride (1973) was nothing short of a miracle in those days when the entire music life was closely observed and severely censored in the former USSR. The aesthetic of Ganelin’s film music led him close to other masterpieces of his time – yet the miracle was that whereas his counterparts lived in free countries never putting their lives and works in any major risk and danger, Ganelin had to struggle with various political obstacles.

Yet this has never diminished or otherwise disfigured his wonderful art of music. Ganelin’s music language was precious everywhere in the 1970s and later – Vilnius, London, Paris, Mexico City, Tokyo, and elsewhere. He kept building the bridges through his music – in the world torn apart by exclusive ideologies and disbelief in humanity. His native Lithuania symbolized for a long time the sad fate and isolation of Eastern Europe, which Ganelin’s music was destined to challenge and overcome; the country of his choice and destiny, Israel, symbolizes memory and its indestructibility– hence, much of Ganelin’s music dedicated to the Holocaust.

Yet another Russia: The Arsenal Kaliningrad Jazz Rock Band

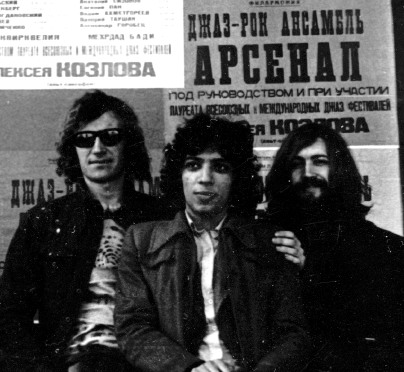

When as a student I heard Arsenal, the jazz rock band of the Kaliningrad Philharmonic, I was dumbfounded: in Soviet times Russian musicians were playing music that jazz lovers at once identified as being under the influence of Chicago and Blood, Sweat and Tears. The leader and spiritus movens of the band was the composer and saxophonist Alexey Kozlov. Later I got the same bang out of the Moscow art rock group Avtograf: after two concerts I heard in Klaipeda and Palanga it was hard to believe they weren’t a British or American group singing in Russian. At times it even seemed I was listening to Yes or Genesis, still my favorite art rock representatives.

So that was a miracle what the Kaliningrad jazz rock band had done. Why Kaliningrad? In fact they were all from Moscow, but they had decided to register the group with the Kaliningrad Philharmonic only to make the Moscow censors and cultural establishment less antsy. They needed a place far off the beaten track in the boondocks ‒ and Kaliningrad was it. The first time Arsenalsounded particularly impressive: not only a strong rhythm group but an excellent wind section as well reminded one of the powerful Americanfusion groups, the big difference being that Arsenal performed a lot of original music, a large part of which consisted of long conceptual compositions.

RELATED ARTICLE: Polish artist and curator Jerzy Onuch on social role of artists and cultural policy

Several years later I heard Arsenal again in Klaipeda; the group had changed considerably. Probably it didn’t want to lag behind the times and deliberately eased off on the more demanding, academic, and conceptual music-making and veered toward a more melodious and popularly acceptable music. It was professional, nice but not as impressive as the first time. Still, there’s something that has to be singled out: the newly constituted band which even performed new wave and late punk rock music also added to its repertoire the American jazz pianist John Lewis’s composition “Django,” first performed by the John Lewis trio and dedicated the memory of the Roma-descended Belgian jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt (django in Romani means I awaken). The young guitarist Viktor Zinchuk, who played the solo part and an improvisation, a decade later became a Russian guitar music star.

In any case, Arsenal and Alexey Kozlov came across as solid, world-league musicians proudly independent of the current power relationships. This was no less important than their musicianship.