Russia’s Strategic Rationale in the “Near Abroad”

Ever since Russia launched its overt aggression against Ukraine in February 2014, the politicians, media and analysts worldwide have been struggling to grasp the logic of Russian actions in Ukraine, especially the rationale behind the Kremlin’s long-term strategy vis-à-vis what it perceives as the “Near Abroad”. Many explanations, models and scenarios have been proposed, ranging from naively optimistic to pessimistic, even catastrophic ones, involving full-scale Russian conventional attacks against its neighbors, including NATO member-states, or attempts to occupy Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia and Central Asia. Russia’s preferred method of 21st century warfare has officially been dubbed “hybrid warfare” by NATO, as even the Russian leadership has adopted this term while accusing the West in aggressive intentions in a typical mirror-imaging fashion.

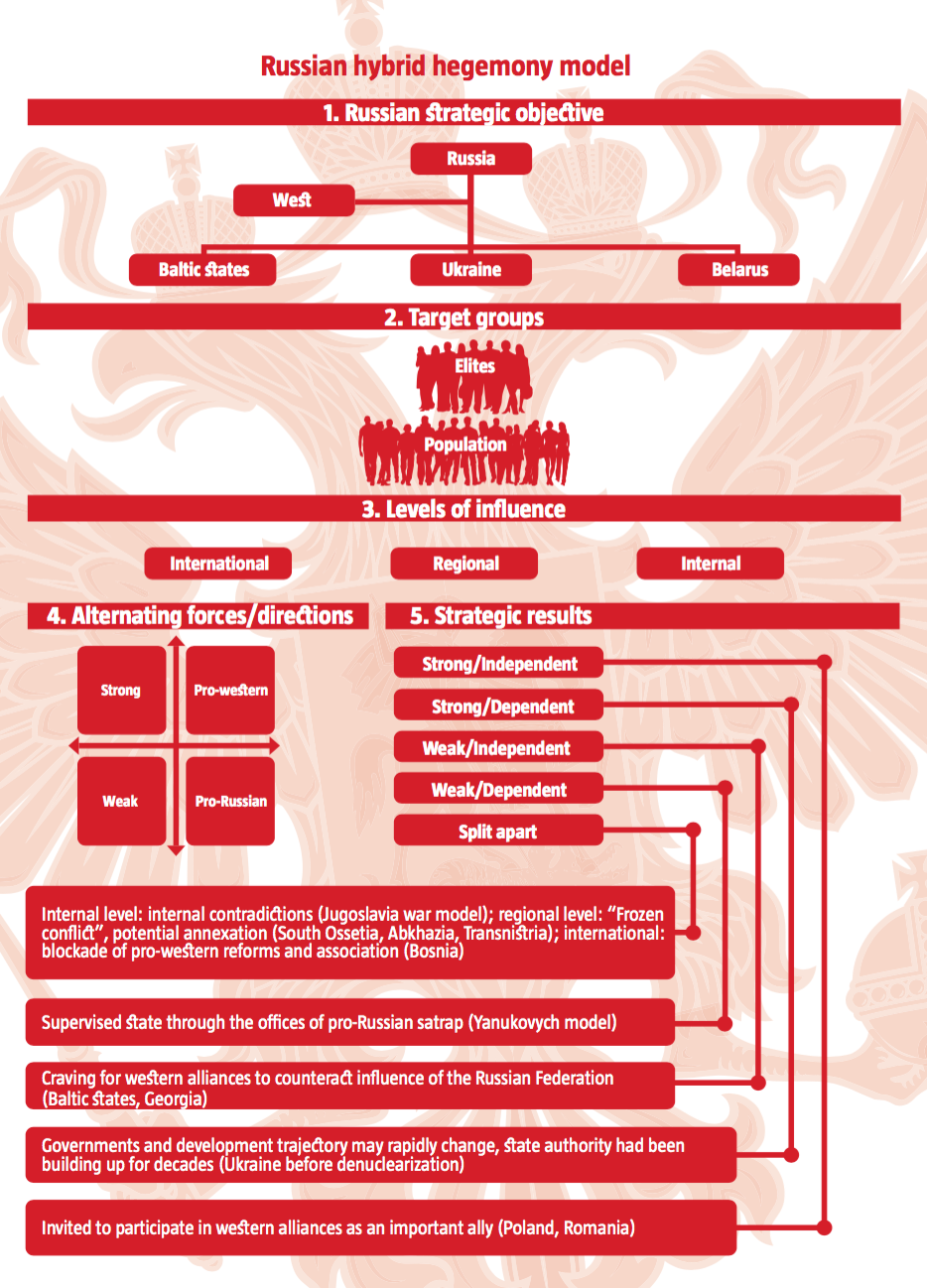

The rationale of Russia’s ongoing aggressive moves – overt or covert, hybrid ones – against the countries along its periphery can best be understood through the following analytical lenses: Russia simply cannot tolerate the existence in its neighborhood of a former Soviet republic that is both strong (with strength being defined as politically stable, militarily modernized, economically viable and socially cohesive) and at the same time pro-Western (that is belonging to, or aspiring toward membership in the EU and NATO). Thus, relative power and orientation are the two basic variables of the “hybrid hegemony” equation that Russia is desperately tying to solve in its favor in the former Soviet space.

The ideal desired outcome for Russia would be to have a neighboring state that is ruled by a pro-Russian regime, which were the cases of both Ukraine and Georgia prior to the 2004 and 2013 revolutions there. If this equation changes and one of Russia’s neighbors chooses a different path leading it toward deeper integration with the West while being governed by a pro-Western elite, then the second best choice for Russia is to have that country divided through a hybrid aggression and annexation of portions of its territory, and keeping it internally divided and weakened, which has been the logic of Russian actions against both Ukraine and Georgia for over a decade now.

The ultimate strategic goal for Russia is to have rings of puppet states along its periphery that face Moscow out of fear for their survival, while at the same time serving both as buffer zones between Russia and NATO, and as convenient launching pads for potential Russian aggressive cross-border moves against the West, hybrid, whenever possible, and even conventional, if absolutely necessary. Russia’s rationale in that regard is based on the lesson that the Kremlin learned twice from the popular revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine, and it is brutally simple and logical: Governments and their rulers can fall and change overnight, but state cohesion (political and social); state power (military and economic), and strategic orientation (popular attitudes, cultural preferences for the EU or Eurasian integration models) are built over years, if not decades.

Russia’s Preferred Strategic Outcomes in the “Near Abroad”

The Kremlin hybrid hegemony strategy can be expressed through a “One-Through-Five” model, whereby Russia has one most desired outcome – to establish uncontested hegemony over Ukraine and the former Soviet space, meaning exerting full control and having the final say in defining all those countries’ foreign and security policies. This objective can be achieved by influencing the two major target audiences in the former Soviet space – the political elites and the populations, by means of hybrid tools – from military to political, diplomatic, legal, economic, infrastructure, information, cyber, intelligence and crime – at the domestic, regional and international levels. The four combinations of the relative power and foreign policy orientation of those countries range from weak and dependent on Russia, to strong and independent ones. The Russian efforts to divide and partition states like Ukraine and Georgia that are trying to escape its rule, result in the fifth strategic outcome – neighboring nations that are becoming stronger and more cohesive and turning to the West, are punished by having portions of their territories annexed in the hope that this will deprive them of their sovereignty and will prevent their integration with NATO and the EU. This particular outcome was recognized by Army Gen. Valery Gerasimov, the Chief of the General Staff of the RF Armed Forces, who in his briefing to the Russian Academy of Military Sciences postulated that: “Hybrid Warfare allows the aggressor to deprive its target-nation of its sovereignty without having to occupy its entire territory” (Gerasimov, 2017).

Ultimately, the strategic outcomes for Russia in order of preference begin with having a weak and dependent neighbor that is controllable through a pro-Russian satrap – the model of Ukraine under Yanukovich and Georgia under Shevarnadze. The Kremlin’s hopes that this would also be the case of Belarus have faced certain resistance from President Lukasehnko after 2014, as he continues to send mixed signals about both Eurasian integration and rapprochement with the West.

When some of those previously dependent nations reject their pro-Russian leadership and choose to turn to the West in a decisive manner, Russia goes for the “partition” model – through direct invasion and annexation of some of their territories, or by providing covert support to one of the parties to an ethnic war. The wars in Yugoslavia in the 1990s provided an excellent testing ground for Russia, as the massive systemic problems they created for the post-Yugoslav successor-states and the entire region, are still being exploited by Russia to this day. They also provide a model for the Kremlin’s constant attempts to de-stabilize the countries in its own neighborhood, especially those in the Caucasus. This is done through the so-called “frozen conflicts”, some of which are actually quite “hot”, and allow for the creeping annexation of Russia-occupied territories, such as South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and potentially Transnistria.

Even having a strong and dependent neighbor is not a preferred option for Russia, based on the same logic as above, namely that governments and orientations change overnight, but state power is built over decades. Following the Soviet collapse, Ukraine had a strong army, a nuclear arsenal, and a powerful industry. Russia was not happy to have Ukraine as a strong regional ally, neither in the period before until 2006, nor during the Yanukovich era. Instead, it opted for debilitating Ukraine in any way it could – by pushing for its de-nuclearization, subverting its political and economic reforms, weakening its army, infiltrating its security apparatus with Russian operative and spies, and filling its political system, legislature and economy with Russian agents of influence. The fate of Ukraine in that period must serve as a stark example to any Russian neighbor who might consider disarming and surrendering their foreign and security policy choices to the Kremlin, as well as a dire warning to anyone in the West who might seriously consider the option of leaving Ukraine, Belarus and others in the Russian orbit, in the naïve hope that they will serve as legitimate “buffer states” between Russia and NATO. They won’t – Russia’s hybrid hegemony will result in them being devoid of their sovereign statehood in all possible ways, until Russia turns them into smaller, weaker, dependent version of itself, to ultimately use them as launching pads for spreading its influence further outside its former Soviet borders.

Even having a militarily weaker, but independents state neighboring Russia is not a preferred option for the Kremlin as such a state will inevitably seek to join the Western alliances in order to balance its power deficiencies. This was the case of the Baltic States – following the Soviet collapse they were militarily weak and were pushing to enter NATO in order to guarantee their security. While Russia did not initially express strong objections to their NATO integration in 2004, the Kremlin quickly changed its attitude when they began having their own independent foreign and domestic policy choices – from asking NATO to provide air patrolling of their borders, to removing Soviet monuments. In response, Russia launched a non-military hybrid effort against Estonia in 2007, that included a massive cyber attack that took down the country’s financial system and organized violent protests of ethnic Russians. The Kremlin’s behavior in the case of the Baltic States provides the best explanation of why Russia objects to the expanded NATO presence and to the EU integration of the other former Soviet republics. When a nation enters the Western security and political alliances, no matter how small or militarily weak, its national security calculus changes, their confidence on the international scene increases, they are more likely to withstand the Kremlin’s pressure, and ultimately – they are no longer so malleable and vulnerable to Russian political, economic, energy and military blackmail. As a result, the Kremlin loses important elements of its “hybrid hegemony” over what is perceives as former colonies.

Ultimately, the worst of all outcomes for Russia is, of course, having a strong and independent state on its borders, as such states are inevitably courted by the West, NATO in particular, as valuable allies. This is the case of both Poland and Romania, and it should be no surprise that their increased confidence in resisting to Russia’s hybrid hegemony – by pushing against Russia’s energy projects to hosting US ballistic missile defense systems and advanced forward presence of NATO headquarters and troops – are causing Russia to issue direct military threats to both nations on a regular basis.

Therefore, when it comes to Ukraine, and to a certain extent Belarus if President Lukashenko continues to assert its independence from Russia by turning to the West, the best outcomes for Russia would be to have a divided country – ethno-linguistically, politically, and territorially; or one that Russia keeps weak and dependent, even if ruled by pro-Russian government. In that regard, the only two possible models of Russian behavior toward Ukraine in the future are: the ‘Satrap’ model (limited sovereignty by controlling the state); or the ‘Spoiler’ model (contested sovereignty by partitioning the state). In more specific terms, those two models can extend from Russian control over Ukraine’s politics, especially in its Russian-speaking territories, to the incorporation of the occupied territories in the Donbas, to potentially claiming the entire Azov Sea as a “Russian lake” by expanding out of Crimea to open a land corridor. The nature of this “zero-sum” game is such that under both Russia-desired outcomes the Western political and security architecture is denied access to most European territories of former Soviet space, first and foremost Ukraine and Belarus, as both countries are too important for the Kremlin to give up – politically historically, culturally, economically and militarily.

The Roles of NATO and the EU in Reversing Russia’s “Hybrid Hegemony” Project in Eurasia

Given Russia’s ongoing aggressive rhetoric and actions, the West and NATO are perfectly justified in worrying about potential future Russian aggressive moves against their member-states in the East, and they should constantly increase the readiness and interoperability of NATO’s forces, while improving military mobility along the eastern border of the Alliance. However, their focus, geographical and functional, should go beyond the purely military threats, and they should be even more involved in the stability of the nations east of the borders of NATO that are targeted by Russia, in the first place Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia and Moldova, but also the other PfP nations. The strategic risk is that masked amidst all the saber-rattling, demonstrations of power and aggressive rhetoric toward the West, the Kremlin is gradually trying to subvert those nations, one by one, and in order to impose its geopolitical will upon them. The new type of domination that Moscow strives to exert in the 21st century over its former Soviet colonies will likely not take the form of multi-million-strong armies conquering everything and everyone between the eastern periphery of the Baltics to the Caucasus and Central Asia, like it happened during the Bolshevik and Stalinist periods. Russia simply does not have the manpower and economic resources to maintain such a war effort and hold perpetually such large territories by force. Still, Russia’s new hybrid hegemony will not be less challenging and dangerous for the West and NATO, as if successfully implemented, it will allow Moscow to stifle, on the cheap, the pro-Western democratic orientation of nation after nation, further and further in the East, until it reconstitutes its former imperial self in a sort of USSR 2.0 “Light” format. If successfully implemented, regardless of the inevitable ups and downs, that would reverse the logic of almost three decades of independent nation-building in the former Soviet space and would fulfill the geopolitical dreams of Vladimir Putin, who in 2005 called the collapse of the Soviet Union “The greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 21st century”. Independent Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia and Moldova still form the best bulwark against this geopolitical nightmare, but many others in the region are at risk of slipping back beyond the “event horizon” of the Eurasian “black hole” that is actively being built by the Kremlin. The West – NATO and the EU – can and therefore must do more to help them resist Kremlin’s “hybrid hegemony” and survive as sovereign nations in the current century.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook