However, what the ratings fail to show is the level of public distrust in politicians which has built as a result of the failures and idle periods of all the governments in the independent Ukraine. This distrust has grown to such an extent, that it impacts the way people behave and expresses itself in the material economic disproportions described below.

How does a person who trusts the government and its policy behave? First of all, such a person is a confident consumer, buying whatever he or she can afford without worrying too much about tomorrow. Secondly, he/she tries to avoid working in any shadow business because in the belief that all taxes and deductions from his/her earnings will be used to meet the needs of society as a whole. In some countries, this confidence is enough to justify huge taxes. Thirdly, such a person saves money on a regular basis, not fearing to lose it to inflation, and trusts his/her money to financial intermediaries investing in securities at best, or bank deposits in a worst case scenario. Finally, albeit not very obvious, a person who trusts the government will buy real estate without worrying that an upcoming economic downturn will knock down its price. People in developed countries still trusted their governments in crisis periods, since at least three of the above elements of behaviour were preserved. In Ukraine, the confidence situation is much worse.

CONSUMPTION

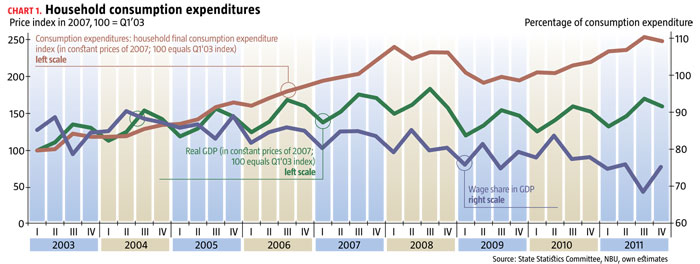

BasedonStateStatistics Committee datafor2011, the consumptionrateinUkrainianhouseholdswasatitshighestofall theyearsofindependence. Household consumer expenditure in real terms exceeded pre-crisis peak rates by 4.8%. Meanwhile, real GDP is still 7.2% short of what the country needs to fully recover after the crisis. The first question these numbers bring to mind is where should the revenues come from to trigger growth at this difficult time? The logical answer would be that the crisis has reduced the revenues of Ukrainian companies, therefore the growing share of wages and pensions to GDP should have been suffucient for the population to consume more until now. In fact, though, the employee payroll, which includes all salaries and most pensions, has declined from 49.6% to 47.7% of GDP. This is in line with the dynamics of the employee payroll to the consumption expenditures ratio (see Chart 1) meaning that a big part of consumption in Ukraine has little to do with wages and pensions, which requires other explanations, several of which are outlined below.

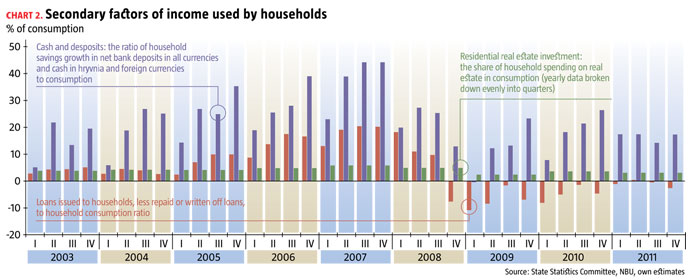

Firstly, Ukrainiansbegan to savelessin ordertosupportthe decentlevel of their own consumption as well as that of family members who lost their source of income as a result of the crisis. This looks credible as the share of personal savings in cash and deposits has plummeted (see Chart 2). Nearly 20 million Ukrainian employees with average monthly salaries of UAH 2,633 (about USD 330) in the past year and nearly 14 million more pensioners with average pensions of UAH 1,152 (USD 144) who often have to support their children and grandchildren, can hardly save anything from their income, and even if they do, the saved money has little effect on consumption.

Secondly, peoplewhoreceivenon-labourincome, suchasrent, interestondepositsand dividends, have begun toconsumemore. This passive income is considerably higher than average monthly salaries or pensions, so the amount of consumption and the choice of goods and services differ significantly from that of the average Ukrainian. Statistics confirm this scenario as the ratio of such income (gross and mixed income) to GDP has changed by merely 0.1% over the past three years, staying at a level of about 38% all that time. Since the average rate of non-labour income allowed its recipients to save before the crisis as well, they had every reason to increase personal consumption, and they continue to do so, regardless of the economic situation. Therefore, the belt tightened by various politicians many times over the past few years, is not on the waist of those who could significantly improve the balance in Ukraine’s economy with their savings. Instead, it is being tightened around the neck of those who have nothing to spend anyway. And this negatively impacts the trust of most of the population in the government.

Thirdly, the considerable growth of visible consumption stems from the equally considerable growth of invisible income from the shadow economy. In addition to salaries in envelopes over which the government is obsessing of late, this income includes unreported revenue from grey imports, trade and production, as well as all kinds of bribes that are unfortunately not accounted for in official statistics. Such revenues add up to a significant amount, that matches the gap between real accounted consumption and GDP in Chart 1. In 2008, a large amount of loans, mostly issued to fund imports and having no impact on GDP, was used to justify that gap. After the crisis, however, households are only repaying loans (see Chart 2), not obtaining new ones, while the gap continues to grow. It is entirely possible that of the 14.8% that was the official decline of GDP in 2009, at least one third did not disappear, but was quietly transferred into the shadow sector, where it currently continues to operate and increase successfully, generously affording the owners visible consumption, and increasing the gap. Hardworking average people, living on their salaries or pensions alone, seeing the sumptuous life of their inventive neighbours, first and foremost, blame this imbalance on the government and the level of order it maintains in the country, something that in no way boosts their confidence in the government.

Fourthly, increasedlendingcan theoricallyboost consumption, but this does not pertain to Ukrainian statistics in the past two to three years. Chart 2 shows that loans issued to households in 2007 amounted to almost 20% of consumption, being a weighty factor boosting consumption growth. After the crisis though, households have been repaying old loans more than they have been taking new ones. This backs the above three scenarios since people who live off of their salaries alone consume less as they repay their loans. Meanwhile, the total consumption rate is growing due to non-labour and shadow income.

OTHER INCOME FACTORS

Household lending shapes opposite trends on the opposite sides of the crisis. Obviously, lending flourished before the crisis and credit leverage in the private sector shrank after the crisis in most economies. Therefore, there is nothing the government can do about them in Ukraine. Something similar is happening to residential real estate investment. It is now at the very end of the consumer priorities chain, as most people buy apartments when they can afford to satisfy their current needs and put some money aside. When the crisis hit Ukraine four years ago, it created a sort of vacuum on the residential real estate market. Those who used to have a higher income bought apartments with the aid of a mortgage before the crisis, while those whose income was somewhat lower, even lost part of it, not to mention the fact that thet lost the opportunity to obtain a loan and buy an apartment. As a result, residential construction dropped to 2.0% of GDP in 2011 from 3.4% in 2007. This also leaves little room for the government to act. Even if it subsidizes part of the mortgage interest rate while earnings remain inadequate, the initiative will not lure enough buyers. Even if the government buys and distributes apartments worth 1-2% of GDP, this will be a significant burden on the budget and will not really change macroeconomic trends.

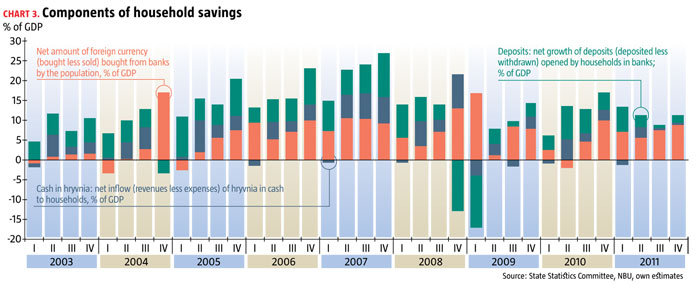

Yet, there is still much that the government can do about some of the other components of household expenditures. One is savings and Ukrainians do not have much choice of assets in which to save their money. It is composed of some basic options, such as keeping cash in foreign currencies, the hryvnia and deposits, and some the less common ones, including real estate, land, securities and bank metals. The dynamics of the key saving options available to Ukrainians shows some interesting trends (see Chart 3). Firstly, savings in cash and deposits fell from 22.0% of GDP in 2007 to 10.9% in 2011 as a result of the crisis, even though these are the most liquid categories of assets. Savings in other assets should have declined at a more rapid rate. As noted above, the income of most Ukrainians does not allow for many savings, therefore the largest decline in deposits probably falls to those who could have saved something, but opted not to restrict their consumption. Secondly, households opt for cash savings rather in other assets that are most liquid. At their peak in 2007, deposits amounted to 8.0% of GDP compared to only 3.0% in 2011. This signals public distrust in banks and the government’s ability to support them in times of temporary difficulties. Thirdly, Ukrainians tended to opt for foreign currencies for their savings, not the hryvnia. In 2007, the ratio of deposits in foreign currencies to those in the hryvnia was 9.4% to 4.6% of GDP. In 2011, this changed to 7.2% to 0.7% of GDP respectively. Despite the decline in earnings and savings, household savings in foreign currencies were just 0.1 of a percentage point less than in 2008. On the one hand, this signals a lack of trust in the hryvnia and the ability of central government authorities to keep it stable. On the other hand, no matter what currency Ukrainians choose to save in, they still “hide it under the mattress”, away from economic turnover and reducing potential total demand, because the mere fact of savings in cash is a reflection of people’s uncertainty in the future.

The above arguments prove how macroeconomic disproportions continue to grow in Ukraine in the post-crisis period, some being the direct consequence of plummeting trust in the government and its policy. It becomes ever-more clear that most Ukrainians living on their salaries and pensions alone are forced to make significant cuts in consumption, while the recipients of non-labour income are not going to save, even if the economic system needs them to. One of the few key ways to ensure their prosperity is to switch to the shadow sector. Meanwhile, with the current level of trust in Ukraine’s financial system and hryvnia, most Ukrainians prefer to exchange their hryvnias into dollars or euros, which they save for better times. With such trends, no matter which political party is in power, popular trust for the government will only be revived when the government starts taking action on a regular basis to balance these disproportions. If a government manages to direct popular savings into the financial system (7-10% of GDP), encourage those better-off to tighten their belts a little (5-7% of GDP) and draw shadow income into the official sector of the economy (5-10% of GDP in extra tax revenues), such government will end up with a huge reserve that will make it possible to revive Ukraine’s economy in just a few years and restore the level of trust that is so lacking in Ukraine today.