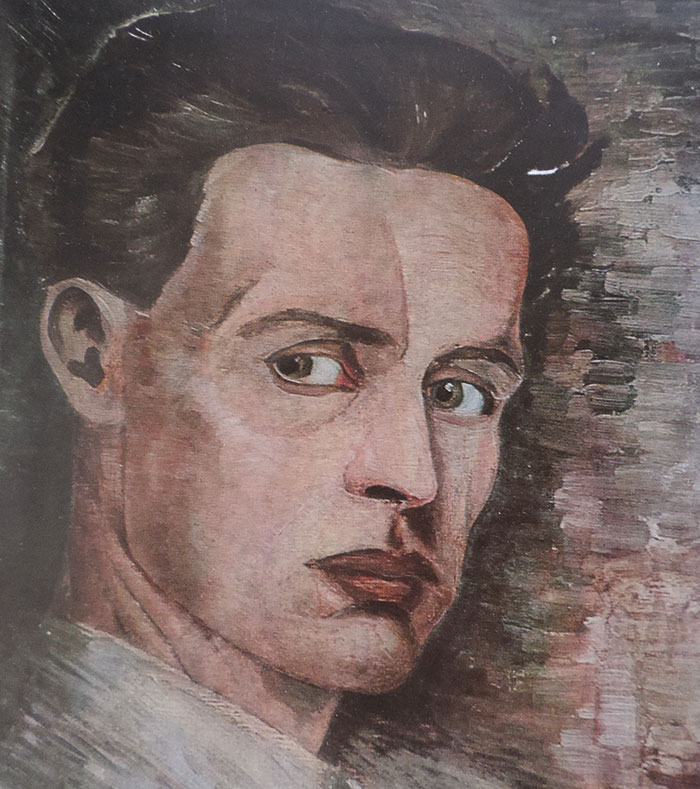

“Our steps in cinematography were attempts of a child learning to walk”

Yuriy Yanovskiy

The Sailing Master, 1927

Cinema triggered a lot of excitement in the 1920s. Ukraine was no exception to this trend: millions were curious about the art of motion pictures. Film studios in Yalta and Odesa made films since the pre-revolution time but intensified production. Established in 1922 in Kharkiv, then capital of the Ukrainian SSR, a special state entity called All-Ukrainian Department for Cinematography better known under the abbreviation VUFKU was in charge of this mass art.

Demand created supply. The new industry needed screenwriters, and many writers switched to that: Dmytro Buzko, Mike Johansen, Hryhoriy Epik, Oles Dosvitniy. Writer Valerian Pidmohylniy initially intended his Misto (City), a popular novel, for cinematography; so did Volodymyr Vynnychenko, a veteran of counterrevolution who then lived in Prague, with his Soniachna mashyna (The Sun Machine), the first utopian sci-fi novel in Ukraine.

Thinking in images. Yuriy Yanovskiy, 1927

The magazine Kino (Cinema) was launched in 1925. Thanks to Mykhail Semenko, an unstoppable generator of ideas, poet and founder of Ukrainian futurism in literature, futurist poet Mykola Bazhan, then 21, was appointed its chief editor. Another of Semenko’s proteges joining the creation of Ukrainian cinematography at its very birth was Yuriy Yanovskiy (1902–1954). He had spent some time working at the screenwriting section of the All-Ukrainian Department for Cinematography before he was appointed art editor of the Odesa Film Studio, also referred to as a Hollywood on the Black Sea coast, in the spring of 1925 at just 25. But his affair with cinematography began somewhat earlier with his novella Mamutovi byvni (A Mamoth’s Tusks) written in 1924. Complex in composition and images, somewhat playful with its parodic component, it ended with mysterious words from the protagonist: “Let the flute cry all it needs, at least at the end of the screening!”, making the audience realize that this was a cry from the heart of an artist longing to do real cinematography, not to simply satisfy the primitive taste of the viewers who were “in love with tricks”. Mykhial Semenko was happy: “His (Yuriy Yanovskiy’s – Ed.) novellas are cinematographic. You can make a film out of every novella. He thinks in shots. That’s someone who should make films!” he said.

Yanovskiy had to move to Odesa to make films. Studio director Pavlo Nechesa, a former sailor, recalled later: “No film was released from Odesa Film Studio until Yanovskiy or Babel who actively cooperated with us reacted or wrote a new script.” Babel fit the Black Sea Hollywood perfectly. His scripts were used for a number of films, including Travelling Stars and Benya the Scream. The author of the famous Odessa Stories, he often featured in Kino. Yuriy Yanovskiy admired the unusual portrayal of events and people in Babel’s Red Cavalry. “I love reading Rudyard Kipling, Edgar Allan Poe, Jack London, O. Henry, Ambrose Bierce, Joseph Conrad, Mark Twain, Chesterton, Tennyson, Voltaire, Anatole France, Gogol, Babel. I don’t like any Ukrainian writers, other than history by Mykhailo Hrushevsky,” Yanovskiy once admitted. Isaac Babel’s ironic and passionate novellas were part of Yanovskiy’s personal model of literature. Illustrative of this are similarities to the Red Cavalryin Yanovskiy’s description of the war conditions in Ukraine in 1919-1920 in his own works.

RELATED ARTICLE: An artist against the machine

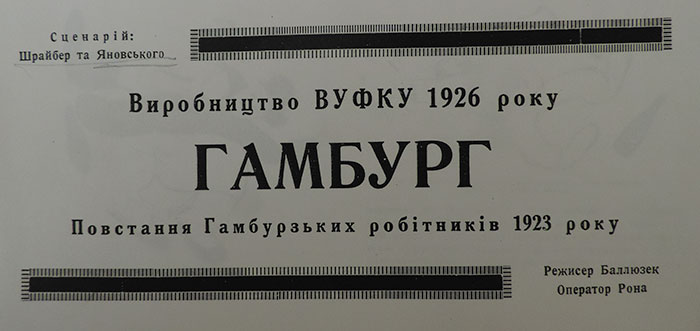

Just like Babel, Yanovskiy edited and “improved” scripts of other people and wrote some of his own. One old poster had the following announcement: “Produced by the All-Ukrainian Department of Cinematography. HAMBURG. An uprising of Hamburg workers in 1923. Script by S. Shreiber and Yu. Yanovskiy.” Director Volodymyr Balleziuk shot the film. Shreiber was a co-author only nominally. He was the captain of a German ship. Yanovskiy met him in Odesa and used his stories for the script. It was Hamburg on Barricadesby Larysa Raisner that served as the starting point for him.

Posters looked intriguing. “All Odesa will speak about the extraordinary film Hamburg,” they claimed. Professor Oleh Babyshkin, the author of Yuriy Yanovskiy’s Film Legacy, a research book published in 1987, claimed that the film was indeed successful. Critics wrote much and well about it. Kinomagazine (No8, 1926) described it as “a great event in Ukrainian cinematography” pointing to the “profound coverage of the revolutionary topic”, directing and technical accomplishments. The audience will no longer have a chance to make its own opinion about the film – it survived as a fragmented copy and researchers never found the original script for Hamburg.

Work with Yuriy Tiutiunnyk

In 1926, a film titled PKP– for Polska koleia panstwowa or the Polish State Railway, or Poland Bought Petliura in an unofficial version, – was shot at the Odesa Film Studio. Yuriy Tiutiunnyk, a general and commander with the UNR (Ukrainian People’s Republic) army, played himself in the film: he had been commandant of Odesa seven years earlier when the army led by Otaman Nikifor Grigoriev entered the city in the spring of 1919. In early May 1919, Yuriy Yanovskiy, 17 at that time, heard and saw Tiutiunnyk read out Grigoriev’s proclamation about quitting the Red Army at the church square in his native Yelysavethrad, later Kirovohrad and now Kropyvnytskiy. Their paths crossed shortly after.

Ukrainian Hollywood. The pavillion where Odesa Film Studio started

UNR Army General Tiutiunnyk was among the key organizers of the Winter Campaigns. In April 1922, the Kyiv newspaper Proletarian Truth published a tough decree of the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee: “Declare beyond law the following persistent criminals attacking the freedom of Ukrainian working people, irreconcilable enemies of Ukraine’s peasants and workers: Pavlo Skoropadsky, Symon Petliura, Yurko Tiutiunnyk, Nestor Makhno, Petro Vrangel, Kutepov and Borys Savinkov.” Tiutiunnyk was granted amnesty in 1923. Just like Savinkov, he was first lured to return to Ukraine from abroad, then arrested, then used for propaganda purposes – including in the PKP film.

The former army commander was a talented writer, so the bolsheviks allowed him to work at the Book Union publishing house. He attended the meetings of VAPLITE, a literature club led by writer Mykola Khvyliovyi. Shortly after that, following the trendy infatuation with cinema, Tiutiunnyk turned into screenwriter under the name Yurtyk. He and Mike Johansen wrote the first script for Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s Zvenyhora. He brought in the key metaphor of Zvenyhora as Ukraine, and it was further enriched with fragments inspired by Taras Shevchenko’s mystique poem The Great Dungeon. Because Tiutiunnyk’s life was closely tied to Zvenyhorodka, a town in Cherkasy Oblast, he shared the local legend of the treasure buried by the haidamaky in one of the town’s hills with Johansen and the story was used for the original script.

The two Yuriys – Tiutiunnyk and Yanovskiy – became friends in Odesa. Yanovskiy grew fascinated with the experienced general-turned-scriptwriter. When a fragment of Yanovskiy’s novel Chotyry shabli (Four Swords) came out in issue 2-3 of the Life and Revolution magazine in 1926, the character Shakhai was clearly inspired by Yurko Tiutiunnyk. A “leader of the peasants’ element”, a person of steel will: “He was extremely in control. Looking calm as a hypnotist, he held the keys to the soul of the entire army.” In Yanovskiy’s novel, Shakhai is an unusual hero in exceptional circumstances. With his unbreaking will, wit and disregard for death, he looks like Jack London’s Sea Wolf and cossacks from Ukrainian heroic epos combined. That symbiosis featured in much of Yanovskiy’s prose.

The fragment has many battle scenes, but it was no place for scrupulous description of reality. It hardly said who exactly Shakhai’s guerillas and their enemies were, making just one reference to the red flag, “intolerably hostile to the blueness and seen from afar… Like a bird bathing in twilight colors… it emerged and soared, waving its wings.” Shakhai’s units fought under this flag. But who was their opponent? Yanovskiy had little interest in historical accuracy. He was fascinated with the creation of “a new poem” to glorify the heroes of the modern time caught in the storm of the history of Ukrainian peasants. Hence the epic element of the story where the author mixes pompous lyricism (“Shakhai looked at his guerillas covered in the dust of victory…”) with “diminished heroism” (“The horsemen, covered in bloodlike butchers, swayed in their saddles…”). Also, the fragment was material for cinema. It had elements similar to the style of Dovzhenko’s films and to Ukrainian poetic cinema of the 1960s.

“The steppe seemed greener overnight. The grass grew by the hour, not by the day. You could take it in your hand and feel it extend and grow. The horse-trodden path extended all the way to the horizon. Horses were rushing.

All of a sudden, the clinging of swords, hats flying in the air and horses neighing notified of Shakhai’s victory. A horseman stormed to the top of the mound and stood there like a monument. His extended hand froze pointing forward as if bronze ran through his veins. The southern sky was burning in the background.”

This is how this fragment titled Raid ends. These could perfectly be episodes from a poetic film with a rapid change of background, a play on metaphors, beautiful movement and a monumental freeze frame at the end. This was literature moving closer to cinema, arming itself with film techniques. Jack London, Guillaume Apollinaire, John Dos Passos did similar experimenting.

Could Tiutiunnyk the screenwriter possibly know that Yanovskiy’s Four Swords, inspired by his Odesa stories about guerilla war, would eventually become a major work of his life?

Yanovskiy and Dovzhenko

Yanovskiy’s closest friendship in Odesa was with Oleksandr Dovzhenko. It started back in Kharkiv where Dovzhenko worked as cartoonist at Visti(News) newspaper under the name Sashko. Yanovskiy knew that his friend just recently returned from Berlin in 1923 where he had been Secretary of the Ukrainian SSR Consulate General and studied at Willy Jaeckel’s private art college in Berlin. Now, in 1926, Yuriy Yanovskiy as art editor of the All-Ukrainian Department for Cinematography easily lured Dovzhenko with opportunities in filmmaking. He first commissioned a poster for the Blue Bag film from him. Then, author Oleksandr Hryshchenko writes in his memoirs, he said to Dovzhenko that “We have few scripts. We need to start it all from scratch. And no script for a children’s film. But we need to develop cinematography for children. Would you write a script for a children’s movie? Be a champion in this genre.” Dovzhenko got excited about the idea. He sat down to think about the storyline that night and was writing a script titled Vasya the Reformer in the coming days.

Artist-turned-director.Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s self-portrait. 1924

Did Yanovskiy bring Dovzhenko to filmmaking then? Yes. But one thing to remember is that the seed fell into the ground that had by then been fully prepared for it. Dovzhenko already felt and realized that his purpose as an artist was not limited to drawing cartoons. A great talent, Dovzhenko could not stay away from the booming cinema. All he needed was some sort of an impulse, and Yanovskiy provided that with his attractive proposals.

The friendship of Yanovskiy and Dovzhenko is good enough for a book. In fact, Yanovskiy wrote those, making Oleksandr Dovzhenko protagonist in his novella V lystopadi(In November, 1925), essay Bayhorod(1927), novel Mayster korablia(Sailing Master, 1928), and Hollywood on the Black Sea Coast, a book of essays from 1930.

“In Novemberwas inspired by my conversations with Dovzhenko,” Yanovskiy wrote later, somewhat mystifying the readers with the reference to “we, the publisher”. “This sweet friend, then an artist, could tell beautiful stories and make up adventures: he was a great adventurer. Once Dovzhenko came home (he shared an apartment with one of our other authors), perplexed and anxious. Sipping wine at night, Dovzhenko told our authors, Bazhan and Melnyk, that it would be nice to blow up the Church of the Myrrhbearers. All the friends, tipsy on the wine, made some of their own stories. Everyone liked that trick. Our author then wrote In November. Now, four years later, we, the publisher proclaim that the spot where the church stood is now vacant. In the future, Kharkiv Theater of Mass Plays large enough for four thousand viewers would stand on the ruins. We have to recognize the author’s accuracy of prediction. The ruining of churches was unthinkable in 1926 and became reality in 1930.”

This betrays Yanovskiy’s style: play with the audience, some scandal, a mix of irony and exaltation. The novella itself, titled after November of 1925, displays a symbiosis of scandalous irony and exaltation, a game and “lyricism encrypted in a personal code”. It features two characters: an artist newly returned from Berlin (Dovzhenko) and his friend, ironically referring to himself as a scribbler (Yanovskiy). Its centerpiece conflict is perfectly in style of classic tradition of Romanticism: an artist’s fantasy clashes with trivial stereotypes of the environment. The artist’s extravagant imagination paints a “grandiose giant city” where there is no dirt and an unusual sculpture of a girl with a sheaf is where the church used to stand. But the prose of sinful reality crushes his soaring fantasy time and again. This creates an effect of the two worlds of Romanticism: the fantastic imaginary one and the trivial real one that stand in contrast to each other.

German Romantic author E. T. A. Hoffmann had similar images of castaway and tragic artists rejected by reality that is hostile to art. In this regard, In Novembermay be one of the most Hoffmann-like works by Yanovskiy. It is filled with provocative jokes and coated in a feeling of mystery. The novella portrays Dovzhenko as a young dreamer, even if his hair starts to grey early, with his unpredictable genius artistic imagination free of banality. It exudes faith in the power of a friend’s restless talent. It also has a trace of an alarming prophecy of the aggressive misunderstanding Dovzhenko would often face in the future.

Successful screenwriting. “All of Odesa will talk about the extraordinary film Hamburgco-written by Yuriy Yanovskiy.” A poster of 1926

Some time later, Yanovskiy dedicated an essay titled Istoriya maistra(A Story of a Master) to Dovzhenko. Published in Kinomagazine in 1927, it had words that sounded like a comment to the novella: “Dovzhenko’s soul searching started after he arrived in Berlin where he went to an art school. He would sit at “the lawn” in our room and explain his interpretation of art. That interpretation was paradoxical. He summarized his work. His paintings, full of sense and storyline, seemed to glimmer in colors. Here an incredible motion froze, a thought reflected on the forehead and painted with a brush. Yet, something small was missing. If only one could touch the context of that painting, turn the character’s head just a little bit more and look at it from a different angle. “There are few of these static moments – I want the living motion of space in the drawing, a story that links emotions of people, alive and warm.”

Yanovskiy shows Dovzhenko’s intense search for places to apply his talent in art in his memories of their nights at the Kharkiv apartment, in “the lawn” – a carpet big enough for several families – where heated discussions about ways of literature, art and cinema took place. Still a cartoonist, Oleksandr Dovzhenko was then at a crossroads in his artistic life. When another friend, poet Mykola Bazhan reflected on those heated conventions in November 1925, he claimed that it was “a breaking point in life” for Dovzhenko, further aggravated by a major tragedy in his family – his wife Varvara got seriously sick and both faced a tough choice. Dovzhenko chose Odesa and cinematography.

“Sev is my first friend. When he came into cinematography as director, he directed the first small comedy and failed brilliantly,” says Editor in Yanovskiy’s Sailing Master. That’s what happened in reality. Dovzhenko’s first films Vasya the Reformer and A Berry of Love directed in Odesa were not successful. Still, his friends believed that his time of triumph would come. “Yanovskiy was fascinated with Dovzhenko, and Dovzhenko was fascinated with Yanovskiy”, writer Oleksandr Hryshchenko recounted. “Impressed by Yanovskiy’s early prose, Sashko (short for Oleksandr – Ed.) said to me: Yanovskiy has a great future. Another time, after Yanovskiy watched Zvenyhora, he told me: Dovzhenko has a great future… They were such great friends, like-minded brothers, to the point that both fell in love with the stunning (actress and film director, Dovzhenko’s second wife – Ed.) Yulia Solntseva who came from Moscow to star in some films. Solntseva chose Dovzhenko. Yanovskiy survived this intimate crash stoically.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Yuriy Andrukhovych: “I don’t like banality, so I don’t meet the readers’ expectations”

Describing this as an “intimate crash” for Yanovskiy was perhaps an exaggeration. But he definitely shared mutual fascination with Dovzhenko. Whoever has doubts about that should read Bayhorod, Hollywood on the Black Sea Coast and the Sailing Master. Here is one fragment from Bayhorod inspired by memories of young years with a character matching Dovzhenko’s features and biography: “A young man in a short coat and a grey hat is waiting for a tram. His clothes are good but look poorly fit, and the hat seems redundant on his big head.” The character works in some institution in Berlin. The image of Dovzhenko is coated in soft romantic irony, as always in Yanovskiy’s works.

Losing the job

Things started turning bad for Yanovskiy as art editor of Odesa Film Studio in the late summer of 1927, even though “director … trusted him fully in all artistic matters, and was benevolent in financial matters”, according to memoirs of Mykola Bazhan. “I fear that The Little Golden Calf by Ilf and Petrov used Yuriy as a prototype for their generous editor willing to offer advance payments and proposing them even to the Ostap Bender characters of which there were plenty around the studio then,” Bazhan wrote ironically.

Heorhiy Ostrovsky, a film expert from Odesa and the author of the well-researched All That Remains book, found an instruction dated August 20, 1927 from Oleksandr Shub, the All-Ukrainian Department of Cinematography board director, where para 6 was a verdict for Yanovskiy: “From this date, art editor of Odesa Film Studio, Comrade Yuriy Yanovskiy is fired for absolute lack of knowledge in cinematography, ruining of films with his editing, and for writing humorous scripts alien to the soviet spirit.” The instruction betrays Shub’s irritation. Something that studio director Pavlo Nechesa turned a blind eye to triggered administrative rage in the high offices. With his arguments on the knowledge of cinematography, poor editing and humorous scripts, Shub took this too far. Apparently, his notion of cinema art made him suspicious of Yanovskiy’s experiments and his exalting and ironic style.

Yanovskiy remained at the Odesa Film Studio until August 1927. He was fired a week before turning 25. Still, his affair with cinematography was to continue.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook