What do you really know about Konotop beyond its legendary reputation for witches? This intriguing tale dates back to the 18th century, as chronicled by the esteemed Ukrainian writer Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko. Although he never witnessed these witches himself—only hearing about them through captivating stories—this doesn’t mean that their presence has vanished. In fact, the opposite may be true. Those with connections to the town often assert that the witch population has only grown and thrived over the years.

Yet, amid the enchanting lore, the city has faced significant losses and destruction throughout its turbulent history, prompting speculation that the witches might have taken flight themselves. Perhaps they soared into the sky on their broomsticks, seeking refuge from the turmoil below. Konotop’s tale of witches is a fascinating blend of myth and reality, weaving a rich tapestry of intrigue that invites both scepticism and wonder.

The cemetery of Wehrmacht soldiers from the Second World War is located in the centre of modern Konotop, in the park near the city council. From the archive of Oleksandr Akulich.

But the intrigue of Konotop goes beyond its witches. This city is a treasure trove of stories—often forgotten, weathered by time, and twisted by history, yet undeniably fascinating and valuable. It would be a shame to let these tales remain unheard, for they are fragments of our rich tapestry of history. Without them, the broader narrative in our minds would remain incomplete. Furthermore, this piece of history feels invitingly untouched. Strolling through its streets, you might find yourself feeling like a pioneer or at least one of the fortunate few granted access to its hidden secrets.

My guide through this city was Oleksandr Akulich, a man whose knowledge of Konotop is nearly encyclopedic. Currently serving as the acting director of the Lazarevsky Konotop City Museum of Local History, Oleksandr’s journey to this role began with his desire to share his hometown. Before becoming a museum professional, he led free tours and initiated significant local history projects. He can spend hours weaving through Konotop’s streets, continually offering intriguing insights. Although not a trained historian—his degree is in engineering design—history is his passion; it is a subject he truly lives and breathes. Thanks to Oleksandr and others like him, Konotop is gradually rediscovering its essence, reclaiming its identity, and unearthing the treasures buried deep within its collective memory.

Oleksandr Akulich near the doors of Malevich.

From Kyiv to Konotop, it’s 250 kilometres by road—a mere three-hour drive or train ride, not far at all. Yet, it’s unlikely that many Kyivans have ventured here for a weekend getaway. To escape the city, one could wander the winding streets of Zahrebellia and visit the spot where Cossacks felled Muscovites with their sabres, enriching our already fertile black soil with the so-called “flower” of the Muscovite nation. It’s a compelling and instructive story—especially relevant today. If we study it closely and interpret it correctly, the lessons learned may help us combat the Russian threat that is ravaging our country.

But Konotop is not just about that. While I initially came to see how the town is coping with the hardships of war, I quickly realised that there is much more to explore. To truly understand and appreciate this town, one must immerse oneself in its past—a past that has been severely eroded and damaged by outsiders. During the Bolshevik occupation, the town underwent a devastating purge of its historical heritage. The local and visiting proletariat worked so tirelessly that they left almost nothing of value—nothing to remind anyone of Konotop’s former greatness. Unique monuments were literally wiped off the earth.

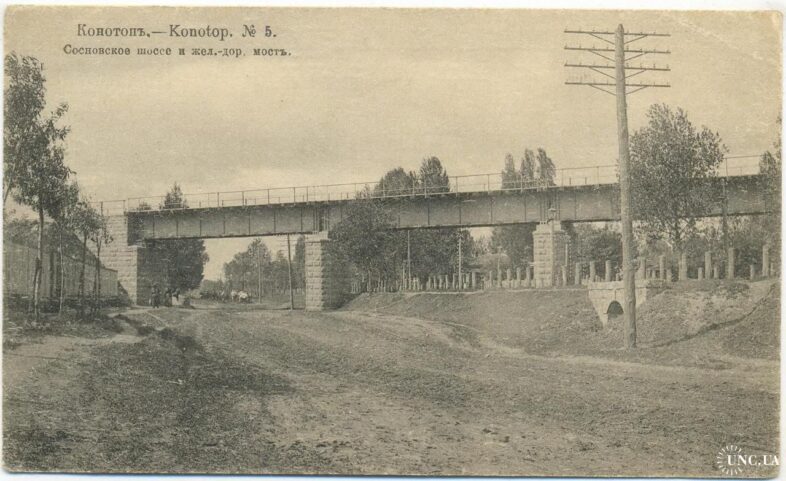

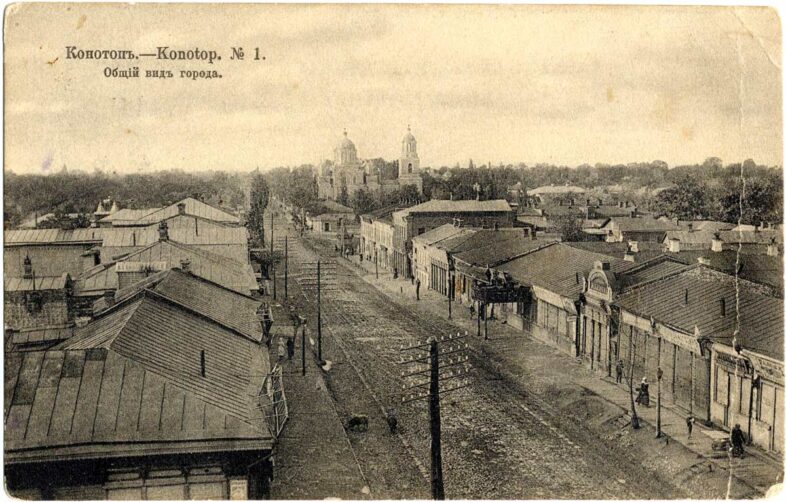

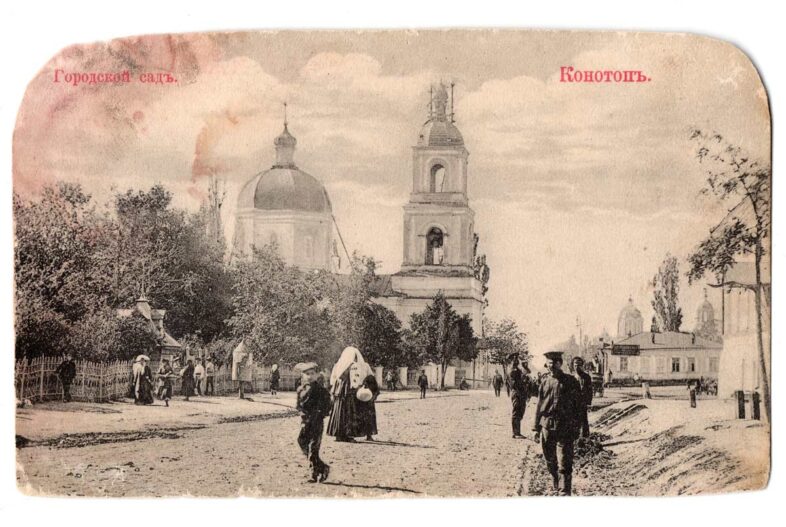

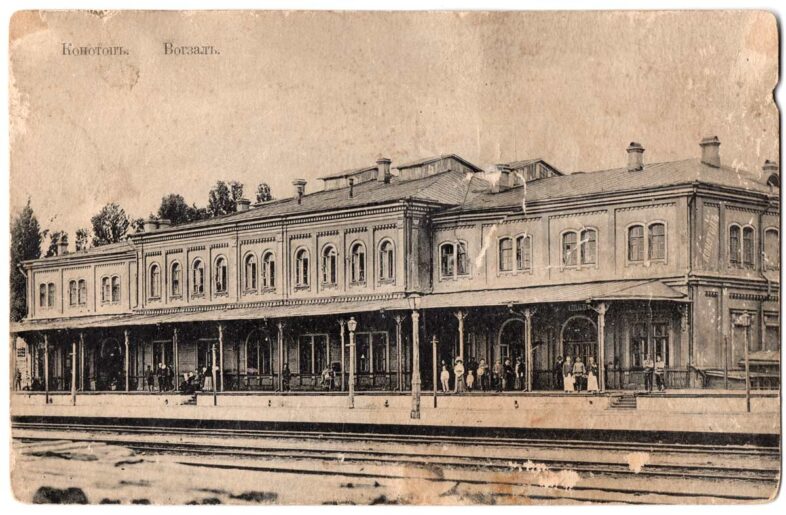

From the archive of Oleksandr Akulich.

Oleksandr notes that only about ten per cent of the historical buildings in Konotop’s old centre remain; the rest have succumbed to destruction. Out of the ten major churches that once graced the town following the Bolshevik coup, eight were demolished. Today, Konotop is frequently described as “gloomy and joyless,” a far cry from its former glory as a jewel of the region, now resembling a neglected post-Soviet town where the passage of time continues to erase the last vestiges of its past splendour. Nevertheless, it is still a place worth visiting, and I will share the reasons why.

At the very least, it’s worth a visit to admire the intricately carved window shutters that adorn many of Konotop’s old houses. These shutters, with their luxurious patterns, are a testament to the craftsmanship of the past. In some homes, you can still find wooden shutters that have stood for over a century—almost unbelievable when you consider that someone once envisioned crafting such intricate mechanisms from wood, which then became a common feature throughout the town.

Interestingly, some residents live for years without realising the hidden marvels on their windows or doors. In Konotop, you can find houses that are over a hundred years old, many of which are still occupied. Some of these homes boast unusual layouts, featuring staircases that lead directly to the second floor, reminiscent of the architecture found in old Odessa, though here they are crafted from wood.

Malevich’s doors.

Konotop is also home to a legendary tavern known as ‘Metro’, which boasts a history spanning at least two hundred years. This establishment has served as a gathering place for generations of locals. Remarkably, the original doors still stand—doors that once opened during the youth of Kazimir Malevich, the visionary behind the iconic Black Square. It is said that Malevich sold his first painting through the very doors of this tavern.

In 2023, Oleksandr and his friends restored these doors, refurbishing the canopy above and even locating the original door handle. “Now, the handle grants wishes,” Oleksandr notes with a smile. More than one visitor has reached out to him after their tours, expressing gratitude and sharing that their wishes have indeed come true.

Adjacent to Malevich’s doors stands a genuine American fire hydrant, reminiscent of those seen in Hollywood films. This rugged model, patented in 1897, is a rare sight in Ukraine, with only six cities featuring this type of open hydrant. In Chernivtsi, they date back to the Austro-Hungarian era, while a few can also be found in Odesa, Kharkiv, and Kyiv. Additionally, there’s one in Huyva near Vinnytsia, the former site of Himmler’s ‘Hegewald’ residence, a symbolic hydrant recently installed in Sumy, and eight in Konotop, some of which are still operational.

The house where the Japanese military attaché resided during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905).

In Konotop, there stands an almost pristine house that once served as the residence of a Japanese military attaché during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). After being expelled from St. Petersburg, he relocated to Konotop as the Japanese forces began to decisively defeat the Russians in the Far East, rendering him unwelcome in major cities across the Russian Empire. Until the mid-2000s, various government offices operated within the building, but following their departure, a fire broke out—an all too common fate for such sites. Left unattended, the house has since fallen into disrepair. Despite its unique wooden shutters and beautiful window frames, which offer the potential for restoration, no one seems willing to undertake the effort.

Konotop boasts a substantial airfield that played a significant role during World War II, serving as the headquarters for the Luftwaffe’s second fleet. The city effectively became a technical aviation hub, from which German planes were dispatched to bomb Moscow. All aircraft designated for operations on the Eastern Front were brought here for inspection and rearmament before being sent to various bases, ranging from the Caucasus to the North Sea.

Today, however, the airfield is out of commission, situated too close to the front lines, with its runway damaged by German forces during their retreat. In its place, a unique aviation museum has emerged, featuring an impressive array of helicopters, including the world’s only preserved Mi-22 airborne command post. The museum also showcases numerous aviation components and a collection of military uniforms spanning different eras. Perhaps the most intriguing exhibit is a recently restored underground Luftwaffe bunker, meticulously recreated to reflect its original World War II condition, thanks to the dedication of local activists and historians.

From the archive of Oleksandr Akulich

Since that time, numerous intriguing photographs have been preserved. For instance, they reveal that during the war years, a substantial cemetery for Reich soldiers existed in the central park of Konotop, directly opposite what was then the House of Soviets (now the Center for Youth Creativity near the city council). According to the Volksbund, a German humanitarian organisation responsible for overseeing soldiers’ graves outside Germany, the cemetery was indeed filled. However, excavations conducted in 2017 uncovered only empty pits, as Oleksandr notes. It is possible that the Germans managed to evacuate the bodies during their retreat, though the efforts of pioneers who settled in the House of Soviets after the war might also explain the absence of remains.

Ultimately, the situation is rather unremarkable. The relationship between the Konotop proletariat and cemeteries has been complex. For some reason, cemeteries were traditionally destroyed during the Soviet era. For instance, the city’s central cinema now occupies the site of a former cemetery, as no other location was deemed suitable for its construction. Several old Jewish cemeteries, which purportedly contained the graves of five tzadiks [a title in Judaism for those deemed righteous – ed.] —one of whom is buried in Uman, a significant site of pilgrimage—have also been dismantled. Today, the grounds of one cemetery host a memorial, while a shopping centre has replaced another.

Furthermore, the first multi-story stone building in Konotop is a prison, standing three stories tall and constructed in 1857. Local legend has it that a Jewish man built this prison as a means to secure his own release from imprisonment. While the truth of this legend remains uncertain, it certainly adds a fascinating layer to the building’s history. Interestingly, the prison is still operational today. Until recently, it housed men, but many inmates volunteered for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, freeing up space for the transfer of a women’s prison from the area near Kharkiv.

Hyperboloid water tower by architect Shukhov.

Adjacent to the prison stands perhaps the most intriguing tourist attraction in Konotop—the hyperboloid water tower, designed by architect Shukhov and built in 1929. This tower was once a vital component of the local water supply system, though its functional life was brief. It suffered damage in 1943 and was never restored, remaining in a state of disrepair until the 1980s when it was repurposed as a television tower for local broadcasting. The tower features a striking single-skin hyperboloid of revolution constructed from 25 pairs of angular metal rods. It rests on a ring-shaped reinforced concrete base with a diameter of 16 meters. Atop the tower, a circular metal platform houses the tank, accessible via a spiral staircase. Towering to the equivalent height of an eleven-story building, it offers panoramic views of the city, making it a favoured vantage point for residents. For thrill-seekers, the climb to the top provides an exhilarating experience, although the tower’s current condition poses some challenges. Oleksandr Akulich says he hoped to restore the tower to make it safer for climbers so that everyone can enjoy the stunning views of the city from up high.

Across Ukraine, there are approximately a dozen such hyperboloid structures, each with its unique character. Unfortunately, some, like the Dnipro lighthouses in the Kherson region, have fallen under occupation, and their current condition remains uncertain. These towers gained popularity in the first half of the 20th century due to their lightweight construction, which enables them to withstand significantly greater loads than traditional brick structures.

The exact date of Konotop’s founding remains a mystery. However, in 2024, we will mark 390 years since the first mention of the city—or, more accurately, the fortification along the border with Muscovy. In October 1634, Władysław IV Vasa, the King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, granted land to landowner Mykola Tsetisov and his descendants for possession under Konotop. Around this time, a fortress was being constructed at the confluence of the Yezuch and Konotopka rivers, destined to become a vital stronghold for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Historians believe that the fortress didn’t just emerge out of thin air. A century and a half earlier, a settlement existed in this area dating back to Kyivan Rus, which some identify as the chronicled town of Lypovytsk, the centre of the eponymous principality. Unfortunately, when the territory of this ancient city was developed in the latter half of the 20th century, archaeological excavations were not conducted, leading to the loss of a significant cultural and historical layer that could have illuminated the area’s past. Archaeologists did manage to excavate at the turn of the millennium near the old market, uncovering some evidence supporting this theory. Yet, substantial research still lies ahead.

It’s also important to remember that after the Mongol invasion, these lands were pretty sparsely populated. People started moving back in during the 16th and 17th centuries, mainly from the Right-Bank and Western Ukraine. Oleksandr Akulich points out that most of the Cossack leaders in Konotop came from the Korosten region, and many of their surnames are still the same as those from that area. Interestingly, just 22 kilometres away from Konotop is the village of Staryi Sambir, which has a name that oddly resembles a town in Lviv Oblast, where the Cossack Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny was born in the village of Kulchytsi. It’s likely that Staryi Sambir was founded by migrants from the Boykivshchyna region, who named it to remember their homeland—a pretty common thing for settlers to do.

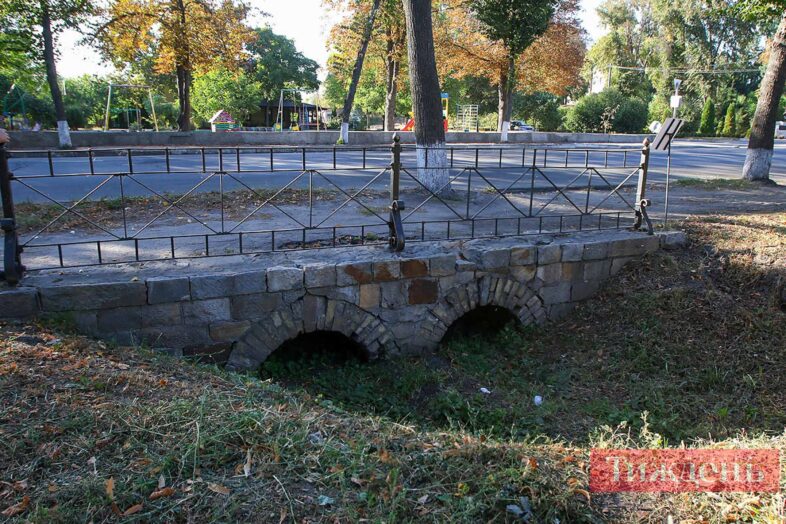

Old bridge over the Konotopka River.

The remnants of the mounds and trenches of the Konotop fortress still stand today, and visitors can climb on them if they wish. The fortress, which existed until 1816, was nearly square in shape and resembled most outposts on the Left Bank, featuring a moat, an earthen rampart, and a palisade. Within its most secure section—the noble courtyard or citadel—were the treasury, gunpowder storage, and the colonel’s house. There’s little doubt that underground passages existed beneath the fortress, as ground subsidence is a common occurrence in the old city area.

The riverbed of the Konotopka has also survived, famously known as the spot where Russian soldiers became mired during their assault on the fortress on May 9, 1659. Today, the Konotopka resembles a typical ditch, with water flowing only in the spring and autumn during rainy seasons. Despite being built over and barely noticeable, the distinctive terrain is the only reminder that a river once flowed through this area, accompanied by a small bridge that has stood for over 130 years.

From the archive of Oleksandr Akulich.

According to a legend spread by Russian propaganda, the name Konotop, as well as that of the Konotopka River, comes from Empress Catherine II. The story claims that the empress was riding through the area when her horses drowned, leading her to name the place Konotop. The issue with this tale is that Catherine ascended to the throne more than a century later, in 1762, well after the city’s founding. What she did contribute to, however, was the destruction of Cossack self-governance in these lands and the beginning of a ruthless campaign of Russification. But, of course, such trivial details never interested the creators of imperial myths.

From its founding, or rather its re-founding, until the second half of the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution reached the city, Konotop was a typical Cossack town, with Cossacks making up the overwhelming majority of the population. By the mid-17th century, during the Khmelnytsky Uprising, it had become a Cossack town strategically located at a main crossroads and undergoing significant development. It served not only as a stronghold but also as a vital centre of trade.

The main job of the Konotop Cossacks was, of course, military service, mainly as part of the Konotop Hundred [a Cossack military unit – ed.] in the Nizhyn Regiment. But when they weren’t off fighting, they, like anyone else, got involved in farming. Those with land worked it, while the wealthier ones dabbled in distilling, beekeeping, and trade. Most Cossacks, however, were skilled in various crafts like furriery, shoemaking, weaving, tailoring, blacksmithing, and pottery.

The Zahrebellia district in Konotop is a living reminder of those times, having somehow held onto its charm if not its original look. This might be because it’s a bit further from the city centre, so no one has bothered to change it much. Oleksandr Akulich calls Zahrebellia an open-air museum from the Hetmanate era, with streets that haven’t changed much since the 1600s, still winding and bending at odd angles. Most houses date back to the mid-19th century and have only been slightly modernised, giving them a unique feel in the 21st century.

The people of Konotop have never forgotten their Cossack roots. Many documents, especially about property rights, back this up. It turns out that the Cossack estate was only abolished in 1927—less than a century ago! Up until then, the descendants of the Cossacks were proud to say who they were, often signing their names as “Cossack so-and-so.”

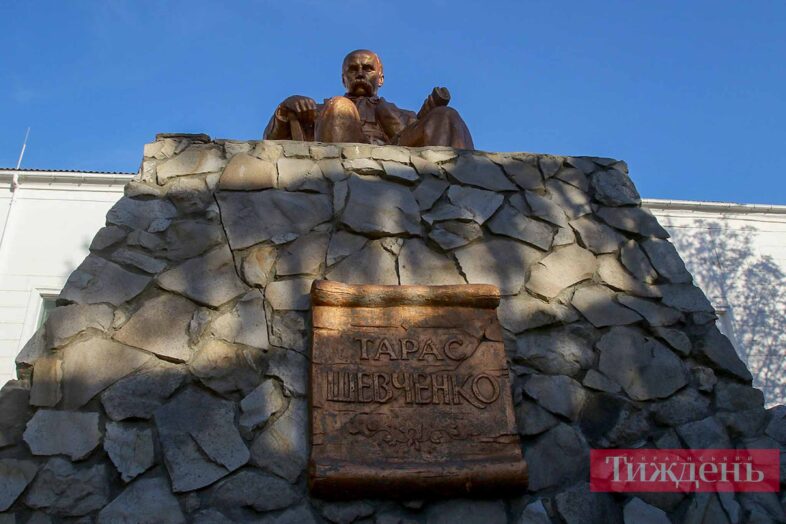

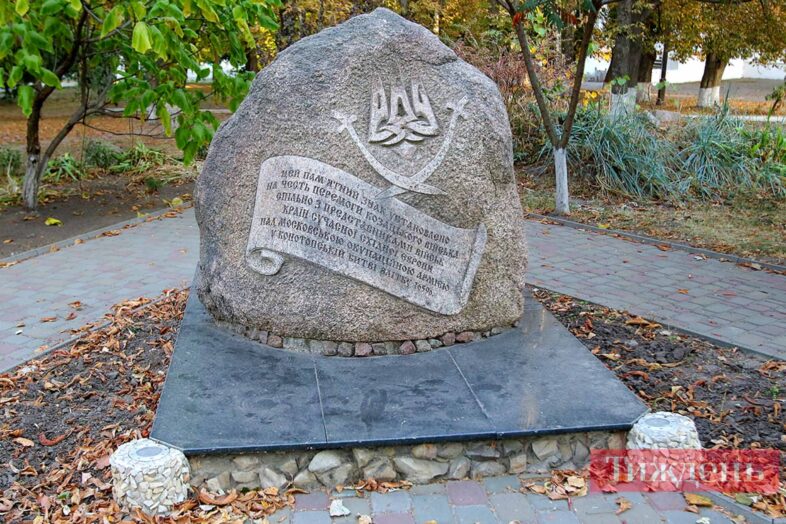

Monument to Colonel Hryhoriy Hulyanytskyi, leader of the defence of Konotop during the 1659 war against the Russian troops commanded by Prince Trubetskoy.

The construction of the Kyiv-Kursk railway in the second half of the 19th century (1861–1868) was a major turning point for Konotop, driving rapid development that transformed the city in both quantity and quality. Workers flocked to the railway workshops set up in Konotop, even coming from the nearby Kursk region, which led to a noticeable increase in the Russian-speaking population. Remarkably, these railway workshops, which were later proudly renamed the Konotop Car Repair Plant (KVRZ) during Soviet times, still stand today. However, since around 2017, the new owners have begun dismantling the old buildings, which hold local significance. Now, anyone arriving in Konotop by train can catch a glimpse of the picturesque ruins behind the station, evoking images of ancient Roman baths in the Eternal City or the remnants of Bakhmut and Avdiivka.

Additionally, Konotop boasted a first-class railway station equipped to welcome royalty. There were only three such stations on this line: in Kyiv, Konotop, and Kursk. Sadly, the station building did not survive; German forces destroyed it during their retreat in 1943. They caused extensive damage during that time, and after their withdrawal, Soviet aviation carpet-bombed Konotop to ensure complete devastation.

From the archive of Oleksandr Akulich.

Memories of those harrowing events linger on both sides of the conflict, shared by those who lived through them. A particularly compelling account comes from the renowned French illustrator Guy Mumin, a legionnaire in the Nazi German Division Großdeutschland who passed away in 2022. In his book, The Forgotten Soldier, he recounts how, faced with the impossibility of evacuating warehouses brimming with food and supplies, he and his comrades took matters into their own hands. They filled their pockets with cigarettes, chocolate, and canned goods, fully aware that the warehouses were fated for destruction.

During the Soviet occupation, Konotop emerged as a formidable industrial hub. Alongside KVRZ, the city was home to another giant: the Konotop Electromechanical Plant (KEMZ). One of only two plants in the USSR specialising in a complete range of mining equipment, from beams to automated systems, KEMZ was a vital player in the local economy. The rivalry between these two industrial titans fueled the city’s growth and even led to establishing a tramway. KVRZ and KEMZ joined forces to build the tracks, and in 1949, Konotop celebrated the launch of its tramway, which was later commemorated with a monument to the tram.

Memorial to the Konotop Battle.

However, the Soviet era should not be romanticised or regarded as a golden age. Quite the opposite—it was a time of destruction for the city and a significant loss of identity, which the residents seem unable to reclaim to this day. According to some accounts, one of the last skirmishes between Ukrainian Insurgent Army fighters in the Konotop region and NKVD troops occurred as late as the 1950s near Krylevec. While the anti-Bolshevik insurgency here was certainly not as widespread as in Western Ukraine, a distinct local phenomenon emerged, where demobilised Red Army soldiers often filled the ranks of the underground. Returning home from one war, they joined the OUN or insurgent units, becoming participants in yet another conflict. Hundreds of such individuals existed, which speaks volumes.

The history of Konotop encompasses many tragic and comical chapters, showcasing events and figures to be proud of, alongside moments of shame. It is impossible to recount all the captivating details in a single piece. Yet, there are even more gaps in this city’s narrative that need to be gradually filled and unveiled. Because, believe me, it’s worth it.