On October 22, an updated online platform, Great Transformations, was launched, introducing new sections on “Instrumental and Vocal Music” and “Kobzars and Lirnyks.” This digital archive for oral history and traditional music originated from scientific expeditions conducted between 1989 and 1994, led by American researcher and ethnomusicologist William Noll.

William Noll is among the first researchers in Ukraine to adopt the oral history method. He directed these expeditions and authored the book “The Transformation of Civil Society: Oral History of Ukrainian Peasant Culture in the 1920s and 1930s”, along with over 20 scholarly works in ethnomusicology, ethnography, sociology, and anthropology.

This online project provides free access to expedition materials for anyone interested in Ukraine and beyond, including ethnomusicologists, ethnologists, historians, artists, journalists, the youth folklore community, and anyone keen to explore.

The first project featured on the platform is “Oral History of Ukrainian Peasant Culture in the 1920s and 1930s.” This section contains materials from expeditions that document the structural changes in economic, cultural, social, and customary practices in Ukrainian villages during the collectivisation period and the Holodomor. It also features accounts of the Moscow genocide in the 1930s and the replacement of traditional culture with a parallel Soviet culture across all aspects of life.

The next phase of publishing expedition materials will include audio and video recordings of transcribed interviews, photographs, and recordings of instrumental music performed by kobzars [a musician playing kobza, a Ukrainian lute-like folk music instrument] and lirnyks [a musician who performs religious or historical songs accompanied by a lira, a hurdy-gurdy like traditional Ukrainian instrument – ed.], as well as folk singing. Traditional Ukrainian music was at the heart of William Noll’s research.

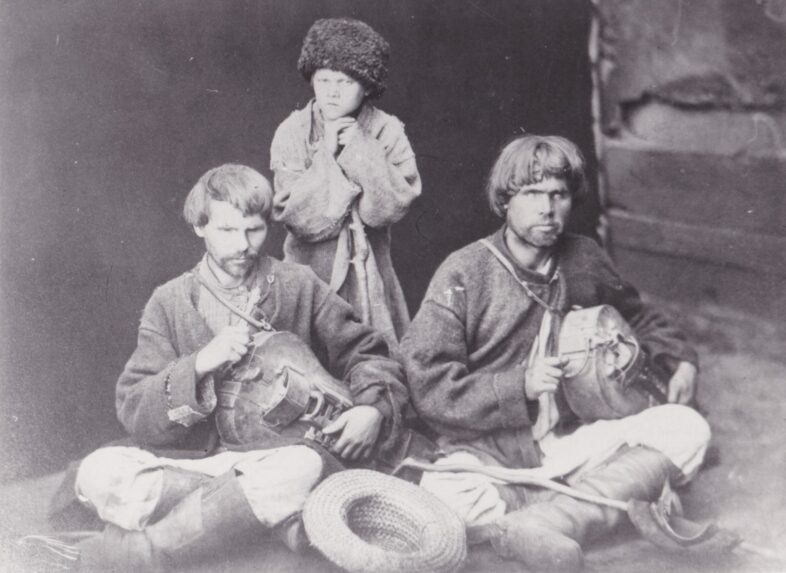

Two lirnyks. Photo from Biliashivskyi archive.

Where did the information about the musicians come from?

In 1989, American ethnomusicologist William Noll travelled to Ukraine to study traditional instrumental music from rural areas. Before this, he had conducted research in Poland, Slovakia, and the USA and had also explored Chinese and Japanese music.

William Noll shared on Facebook, “The goal of my first nine-month journey to Ukraine in the late 1980s and early 1990s was ethnomusicological—to record instrumental music. I was welcomed by the Institute of Art Studies, Folklore, and Ethnography (IMFE), for which I am very grateful, as well as for all the help and support.”

In the 1990s, Noll continued his research at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, the Kyiv Conservatory (now Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine), and the Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore and Ethnology.

During his early trips to Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union, William Noll was constantly under KGB surveillance. As an American exploring sensitive topics like the Holodomor and collectivisation, he was viewed as a potential threat. On his first visit, authorities even attempted to detain him in Moscow to prevent him from entering Ukraine.

William Noll recalled, “I often travelled in ‘paziks’ [small minibuses – ed.], while KGB agents followed me in ‘Zhigulis.’ But somehow we managed—both they and I… It was the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. They just followed me all the time, and I knew they were watching me…”

The expedition trips were meticulously planned and often lasted a long time. For instance, in the summer of 1992, a trip organised by Valentyna Borysenko from the Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore and Ethnology lasted an entire month, during which researchers visited villages in the Chernihiv, Sumy, Poltava, and Kharkiv regions of Ukraine.

From 1993 to 1995, the NGO “Centre for Research in Oral History and Culture” conducted expeditions across various regions of Ukraine at the initiative of William Noll. During these expeditions, researchers interviewed over 400 rural residents who had lived through collectivisation, either as older children or adults.

William Noll created unique recordings of traditional Ukrainian music using professional audio and video equipment, capturing everything from calendar-ritual songs to rural instrumental music, as well as stories about kobzars and lirnyks. He shared, “We received a grant from IREX that enabled us to travel and purchase cassettes and tape recorders. Later on, I also got support for publishing a book with these interviews.”

For the expeditions, William Noll brought together a team of skilled collectors, including Valentyna Borysenko, an ethnologist and Doctor of Historical Sciences who now heads the Department of Archival Scientific Funds of Manuscripts and Sound Recordings at the Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore and Ethnology.

The team also included Vira Zaychenko, the leading researcher at the Chernihiv Historical Museum; Halyna Korniienko, a researcher at the Cherkasy Regional Local Lore Museum; and Mykola Korniienko, the head of the Department of Ethnography at the same museum.

Additionally, Serhiy Kryvenko worked as a researcher at the State Archive of Cherkasy Region; Lydia Lykhach co-founded the NGO “Centre for Oral History and Culture Research” and is a researcher and collector of peasant art as well as the founder and chief editor of the magazine Rodovid in Kyiv. Rounding out the team were Larysa Novikova, an ethnomusicologist and associate professor at the Department of History of Ukrainian Culture at the Kharkiv National Academy of Municipal Economy; Antonina Palahniuk, a telejournalist in Kyiv; and Vladyslav Paskalenko, an engineer and researcher at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv.

Among those who contributed to the recording of traditional music were Mykhailo Khai, an ethno-organologist and later a Doctor of Arts, who served as the head of the ethnomusicology department at Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore and Ethnology and was a professor at the National Music Academy of Ukraine; he was also a lirnyk and a bandurist [a musician who plays a string instrument known as the bandura – ed.], as well as the leader of the folklore group “Nadobryden.”

Svitlana Stefanyshyn from the Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore and Ethnology and photographer Serhiy Marchenko also played important roles in the project. Additionally, Oles Sanin, a film director, cameraman, producer, and talented kobzar, lirnyk, and bandurist, brought his expertise as a master of musical instruments to the team.

William Noll reflected on the experience, saying, “What surprised me most was the enthusiasm of the researchers. They were eager to conduct interviews, engage with people, and collaborate with me. It was a genuine pleasure to work alongside them and discuss our meetings and conversations.”

Ethnomusicological materials of the Great Transformations platform

In the latest phase of the Great Transformations project, funded by the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation (UCF), a new generation of folklorists has joined the effort to process materials on traditional music. Yaryna Dron, a folklorist and musician with the US Orchestra, focused on instrumental music, while vocal music was managed by Iryna Baramba, the leading folklore specialist at the Centre for Folklore and Ethnography at the Educational and Scientific Institute of Philology at Kyiv National University, and a singer in the GG HuliayHorod band.

The website features unique, high-quality colour video recordings from the 1990s, including interviews with a molfar [a shaman-like person believed to have magical abilities, a belief common in Ukraine’s Carpathian region – ed.] Mykhailo Nechai and performances by one of the last kobzars, Heorhii Tkachenko, as well as reconstructions of the kobzar-lirnyk tradition by Mykola Budnyk, Taras Kompanichenko, and Oles Sanin.

These ethnomusicological materials were fieldwork recorded across several regions of Ukraine on the Left Bank of the Dnipro, along with oral history content from Cherkasy, Kyiv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Volyn.

The recordings include lyrical and ritual songs, primarily wedding songs and carols, as well as psalms, memories of rituals, and entertainment at crossroads, dawn, and in social clubs, along with accounts of musicians and folk dances. The collectors focused especially on the religious life of the villagers, while William Noll was particularly interested in how the tragic events of Soviet rule impacted rural musical traditions.

Lidiya Lykhach explains, “William came to Ukraine and began recording a trio of musicians who played at rural weddings and other family events—instrumental rural music was his main focus. He was also keen on kobzars and lirnyks, wanting to understand the context of their lives, but there was little literature available on the subject. He asked his fellow musicologists, ‘Why aren’t you recording the collective farms [Soviet state-run farms – ed.] and what happened after they were established?’ One of his friends replied, ‘We’re not interested in politics.’ So, Bill devised a large project to study these issues in the context of post-collective farm Ukraine.”

William Noll reflects, “What struck me most during this expedition was how, despite all the tragedies and new [Soviet – ed.] cultural norms, people continued to uphold their ancient rituals, traditions, and the stability of life.”

Larysa Novikova, who participated in expeditions in Ukraine’s Slobozhanshchyna region, noted, “The conversations with the respondents revealed the extensive destruction of ways of life, enduring values, and centuries-old beliefs. Most importantly, it highlighted the devaluation of both individual lives and life in general. I even added a personal focus to the existing questionnaire, specifically addressing everything related to rituals, their decline, and certain songs and musical instruments.”

To supplement his research in the 1990s, William Noll gathered materials from several sources, including Lviv ethnomusicologist Bohdan Lukaniuk, who focused on weddings in Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, and western Khmelnytskyi, as well as contributions from Mykhailo Khai, lirnyk Yarema, and other musicians.

How can oral archives collaborate with a digital platform?

The platform serves as an open digital archive of oral history and music for researchers, housing archival audio, video, and photographic materials created through the oral history method, all thematically linked to the Great Transformations. This has enabled the project to incorporate archival materials, such as spring songs, harvest songs, and lyrical songs from Volyn collected by Nina Povar, which will soon be available for everyone to explore on the archive’s website.

Excited by the publications on the Great Transformations social media channels, many Ukrainians are sharing their memories on the archive’s Facebook and Instagram pages. They recount stories about the realities and ancient traditions of their communities and families.

The interviews featured on the Great Transformations platform illustrate how individuals can delve into their family history by engaging older relatives in conversations about the historical events that have shaped their lives.

In his book, William Noll shares a questionnaire that was used during interviews conducted on expeditions in the 1990s. While 30 years have passed, researchers in the 2020s are still documenting memories of ancient rituals and songs, as well as personal accounts of how people navigated life under Soviet governance while preserving their ancestral customs. Today, it remains possible to record ritual songs, as demonstrated by the expeditions undertaken by the author of these lines and his fellow ethnomusicologists.

Moreover, social networks and internet archives have emerged as valuable resources for studying traditional musical culture and oral history, complementing the work done on expeditions.

The Great Transformations platform is incredibly relevant today. It provides a crucial source of living testimonies about Ukraine’s history, especially amid the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war, as Ukrainians fight for their right to tell their own story and shape their future.

The Centre for Oral History and Culture plans to transfer William Noll’s archive of cassette recordings, which document changes in Ukrainian peasant culture during the 1920s and 1930s, to Lesya Hasidyak, the director of the Holodomor Museum. Meanwhile, the original audio and video recordings will be handed over to Valentyna Borysenko, head of the Department of Archival Scientific Collections of Manuscripts and Sound Recordings at the Institute of Ethnology.