When asked which book he was reading, a Ukrainian oligarch pulled out Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. “I really like it,” the billionaire said. Rand refers to US antitrust policy as something close to the world’s greatest evil, standing in the way between America’s most proactive class and the earnings they deserve. It looks like Ukraine’s Atlases have nothing to worry about.

The government uses two antimonopoly approaches. Officially, those in power condemn monopolies, passing a national program to develop competition in Ukraine from 2013-2023. When the cameras are off, however, they support companies that dominate the markets and are owned by people close to the administration.

The state plays a major role in the establishment of monopolies. A typical scenario involves the authorized purchase of strategic companies and their concentration. “There is no punishment for officials who authorize the establishment of big cartels. If specific people were held liable for these decisions, they would probably be more careful,” comments Oleksandr Zholud, an analyst at the International Centre for Policy Studies.

A good example is the position of Rafael Kuzmin, First Deputy Chair of the Antimonopoly Committee, who insists that Dmytro Firtash and Rinat Akhmetov, two Ukrainian tycoons referred to as key Party of Regions’ sponsors until recently, are not monopolists. Meanwhile, independent economists estimate that DTEK, a group of power plants owned by Rinat Akhmetov, controls over 35% of the electricity supply market. Dmytro Firtash’s entities control 100% of facilities producing ammonium nitrate and nearly 50-60% of ammonia and urea production facilities. Meanwhile, Mr. Kuzmin refers to the Privat Group as a monopolist. The group is owned by Ihor Kolomoyskyi and Hennadiy Boholiubov who are still outside the Party of Regions. However, Mr. Kuzmin admitted that the Antimonopoly Committee had no proof of Privat Group’s monopolistic activity because its different companies are owned by various offshore entities.

Ukrtelecom, a major Ukrainian telephone operator, has recently been bought by a little known company linked to the president’s family, according to The Ukrainian Week’s sources. Prior to being sold to private investors, Ukrtelecom had been on the list of natural monopolies dominating the nationwide markets for local telephone service and telecommunication channel rental. However, it was removed from that list in June 2011 although the company controls nearly 70% of the city landline telephone market and 75% of the intercity and international telephone connection markets.

THE WINDOW-DRESSING COMMITTEE

Despite its enormous staff of 229 at its headquarters and 559 at regional branches as of December 31, 2011, the Antimonopoly Committee has failed to effectively prevent monopolies from increasing their hold on Ukraine’s economy.

According to its official data, the most competitive markets included those for trade, intermediary services and agriculture, while the least competitive ones were some sectors of the fuel and energy industry, transport and communications, and utility services. Still, the Antimonopoly Committee turns a blind eye to the industries where real monopolization affects the public indirectly. These include mining and steelworks, chemical industry, construction, auto manufacturing, and a slew of agriculture sectors, such as the supply of equipment, harvesting and storage of food, as well as food processing. These industries are owned by powerful oligarchs who utilize their top government connections to place pressure on the Committee. Virtually all Ukrainian dollar billionaires have their assets concentrated in these few industries.

Another factor that hampers the struggle against monopolists is Ukraine’s legislation, which, unlike American antitrust laws, does not qualify a company’s monopolist position as a violation. Thus, a company may control 50% of the market and nobody will pay attention provided that it tolerates other players (at least from the Antimonopoly Committee’s standpoint, even though the Committee may be encouraged to take a selective approach).

Antimonopoly authorities in developed countries disclose the registers of private corporations displaying elements of domination. Even the Russian Antimonopoly Service keeps a record of commercial entities whose share on a certain market exceeds 35% or commercial entities that dominate in specific markets. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Antimonopoly Committee’s press service told The Ukrainian Week that “Under the effective Law on Natural Monopolies, the Committee is required to keep a record of natural monopolies, but not other monopolies.” How effectively can the state protect competition by following this procedure?

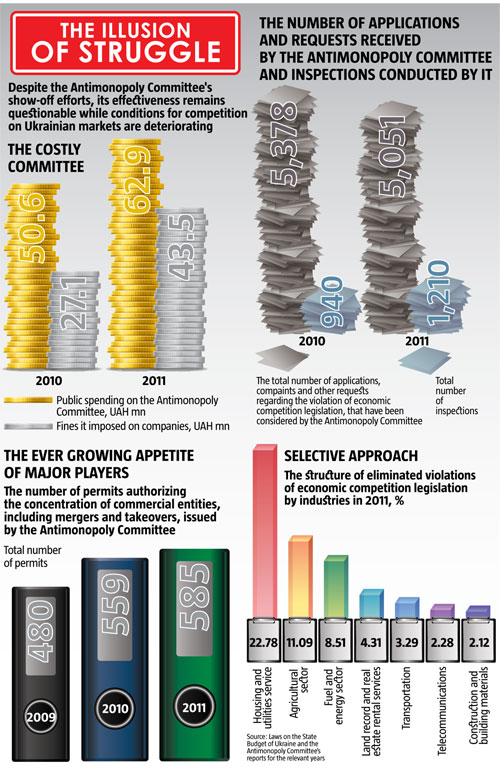

Given the Antimonopoly Committee’s annual reports, its operation is focused on confirming the amount of work it has completed over the course of a year in order to justify its cost rather than to discover and eliminate the monopolization of specific markets. The measure of its efficiency is the number of inspections and revised complaints about antimonopoly law violations, the rate of monopolization aggravation compared to the previous year, and the amount of fines paid to the public budget which are later spent on the Committee. In fact, though, expenditures on the Committee are many times higher than the rates of antimonopoly fines. Meanwhile, the fines, just like any other tool of influence, should only be used for the purpose of real de-monopolization of the economy and the support of competition, which Ukraine currently lacks. Ukraine is 117th – seventh from the bottom – in the economic freedom survey published jointly by the American CATO Institute, the Canadian Fraser Institute and over 50 expert centers. Even other authorities including Ukraine’s Audit Chamber note the Antimonopoly Committee’s inefficiency. Year after year, the Audit Chamber writes in its annual reports that Ukraine has not yet established a system to counteract and prevent monopolies, adjusted its antimonopoly legislation to the EU competitive policy standards, systemized and monitored violations in the markets for commodities by branches, analyzed the competitive status of commercial entities, or examined monopoly (dominating) entities. The Antimonopoly Committee does not report the outcome of violations or its response to discovered violations, the amounts of illegal profits, or financial standing of violators. Experts believe that this may signal backstage arrangements between violators and representatives of the authorities that are in charge of supervising them.

To conduct market analysis, the Committee should cooperate with the relevant regulators of the financial sector, telecommunications, infrastructure, agriculture and other sectors. When asked by The Ukrainian Week, the Antimonopoly Committee representative said that it collaborates with the National Committee for the Regulation of Communications and IT, National Committee for the Regulation of the Energy Sector and the Council for Electricity Wholesale Market. Yet these authorities do not conduct effective control either. The Audit Chamber’s report on the efficiency of spending by the National Committee for the Regulation of the Energy Sector in 2008-2011 said: “the Committee’s existing system to control monopoly companies on Ukraine’s energy market is inefficient, therefore their violations of the legislation have become systemic. The Antimonopoly Committee often failed to apply any relevant measures against violators.”

The inefficiency of government policy to protect competition is proven by the situation concerning the payment of fines. It looks like the Antimonopoly Committee uses fines as the key proof of their influence on the violators of antitrust rules. The Committee boasts multimillion UAH penalties while in fact these do not come close to the amount of profit earned by companies caught red-handed. Moreover, only a portion of the fines goes to the budget. In 2009, for instance, the Antimonopoly Committee imposed penalties worth a total of more than UAH 289.8mn (nearly USD 36mn) while only UAH 12.2mn (USD 1.5mn) reached the budget.

The procedure for imposing fines is non-transparent since there is no methodology to define fine rates and the criteria for doing so are not disclosed. Moreover, purely nominal sanctions are often imposed that do not match the benefit the violators gain from their anti-competitive actions. In 2010, five operators of the oil product market were dealt a combined fine of UAH 139,000 (nearly USD 17,000) as a result of unjustified gas and diesel price increases. In 2011, fines imposed by the Antimonopoly Committee totaled at UAH 43.5mn (USD 5.4mn) with at least 20 cases resulting in penalties that exceeded UAH 100,000 (nearly USD 12,000) per each. The biggest fines included UAH 6mn (USD 0.7mn) for SlavAgroPromService, a wholesale fuel trader; UAH 1.68mn (USD 0.2mn) for Poshtovyi Mahazyn (Post Store), an info service; UAH 1mn (USD 125,000) for DniproAzot, a chemical plant; and UAH 0.5mn (USD 62,500) for Kherson OblEnergo, an electricity supply company in Kherson Oblast. Notably, none of these were controlled by pro-government oligarchs at that point.

Meanwhile, the Antimonopoly Committee mostly focuses on sectors suggested by the government, which often looks like a political instruction. The government tends to wait until just before elections to point out what it calls “unjustified price increases” on consumer markets which, however, are most often perfectly in line with the market situation. This serves to mitigate the effects of inflation on the regime’s popularity. Therefore, few are surprised that the Antimonopoly Committee mostly looks at the agricultural sector which includes markets for foods such as bread, flour, sunflower oil, eggs, milk, butter, sugar and so on, or local level sectors. Thus, the monopoly or dominating status was mostly abused in the housing utilities sector in 2011 – it accounted for 32.5% of all violations revealed.

All things said, the general situation is as follows. There is no list of dominating companies. Corporations close to the administration may enjoy indulgence in the antimonopoly sector. Economic policies meant to protect free markets are blocked by the lack of efficient collaboration between authorities, and meanwhile are used more and more often to apply pressure to the rivals of favored monopolists. The judiciary only helps violators evade fines.

In 2011, President Yanukovych instructed the Antimonopoly Committee to focus on examining the unions of multi-apartment block owners. Thus, in summer 2011, it performed over 3,000 inspections of these unions. In 2012, before the upcoming election, the Antimonopoly Committee’s priorities include protection of entrepreneur and consumer rights, and interests in sectors of social significance. These include bread production, markets for administrative, housing, utility and ritual services, the pharmaceutical industry, and others. These measures act as “social pain killers,” yet they do not disturb the monopolistic foundation of Ukraine’s economy or the industries whose current “oligarch vs. riffraff” model of society continues to hamper Ukraine’s progress.