As a result ofAs a result of Stalin’s “top down” revolution, conventional patriarchal families of the industrial epoch, whose women Lenin described as “domestic slaves,” were replaced by the new “etacratic gender model.” (see glossary)

Unlike in the West, where emancipation evolved through a natural and lengthy process, the Bolsheviks’ gender policy was about the straightforward acknowledgement of equality between men and women. The biological difference between genders served as a marker that outlined social roles. This is clearly demonstrated in The Wedding in Malinovka, a soviet film in which the protagonist, Oksana, is referred to as “an average person, but in braids.”

UNWRITTEN RULES

Meanwhile, the government promoted the special role of women in society, defining the limitations of the dominant gender contract (i.e. the unwritten rules of interaction, rights and duties of men and women in private and public spheres.) Women were involved extensively in physical labour, including the most difficult work, a tradition that entrenched itself so deeply that many Ukrainian women are still ready to toil under difficult conditions for mere pennies. Together with civil activity, this integration led to an increased social significance for women that included a growing range of duties and more responsibilities. Under the Bolshevik model, a woman had to work full-time, raise children, tend to the household and take care of elderly family members.

The state mobilized the work of women beyond the immediate economic necessity, and motherhood became their civic duty. The cult of motherhood promoted in the USSR under Stalin had a purely pragmatic basis: it was created to increase the population.

The USSR’s Family Law of 1968 confirmed the central role of women in the family, defining it as “providing the necessary social conditions for a happy combination of motherhood with increased active and creative involvement in industrial and socio-political life.” However, maternity leave was in fact quite short, allowing only 56 days before childbirth and 56 days following. The logic was simple: the role of women in industrial production had to be maximized. It was not until the 1980s that soviet mothers were granted extra leave for childcare until the baby was 18 months old, although this leave remained unpaid.

In the Soviet Union, child support benefits were only paid for the fourth baby, while the average soviet family had three or fewer children. Working mothers were most useful to the state.

However, this access to a wide variety of jobs and declared equality did not apply to the realm of politics. Women could only be members of the party, and were closed out of its administrative ranks. They occupied nominal administrative positions such as heads of councils, trade unions and Komsomol organizations, while the soviet party nomenclature remained clearly patriarchal. Yekaterina Furtseva was the only woman to serve as a government minister in the Soviet Union.

The only women worthy of respect were the ones that did men’s work. Soviet salaries were low enough to compel people of any gender to work all the time to make a living. As a result, a wife living in this unique “socialist paradise” could never expect her husband to fully support her. A woman who opted for a conventional lifestyle, such as taking care of the house, giving birth and raising children, faced public scorn as an idler, loafer or “princess.”

For a very long time, the official ideology resented the sexuality and physicality of soviet female workers. This social taboo was especially visible in fashion. As the cult of personality dominated the Soviet Union, clothes that accentuated women’s figure were banned. Until the mid-1950s, Ukrainian women wore no low necks, used padded shoulders, and were clad in long loose skirts. Soviet clothing was supposed to hide women’s beauty and be as humble and primitive as possible. Soviet sociologist Igor Kon described the policy as “genderless sexism,” because the identical treatment of both genders did not give women the right to express themselves physically. Meanwhile, bodily self-expression had become an integral component of 1950s-1960s emancipation in the West. Red propaganda spent the following two decades reinforcing the contrast between the decent soviet woman with high morality and the amoral Western female.

ATROPHY OF MEN’S RESPONSIBILITY

This threefold burden on women was accompanied by the gradual transformation of the institutions of marriage and motherhood and the reduction of men’s responsibilities. Backed by tough state regulations, the new gender system gradually dissolved men’s responsibilities to their families, pushing them to the sidelines and leading to their moral regression.

This massive emasculation was augmented by world wars, widespread repression, famines and ethnic purges, resulting in irreparable demographic damage in several countries, including Ukraine. Demographers claim that wars, epidemics and famines are the three factors that affect men the most severely. Yet, with its sweeping repressions, Stalin’s regime had a disastrous effect on mass psychology, compelling the nations under its control to “keep quiet” and “behave like everyone else” in place of the traditional patriarchal superiority of men inside and outside the household. As a result, men compensated their unhappy egos with alcohol and daily brawls that both party and local executive committees failed to deal with until the very end of the USSR. Thus an outrageous disparity arose between the exaggerated masculine identity displayed by men to friends at the local bar or wives in the kitchen, and their inability to embody this identity. This is how the totalitarian regime destroyed the most passionate part of society and ushered in a spirit of servility that exacerbated moral decay, especially among males–those more or less involved in the socio-political sphere.

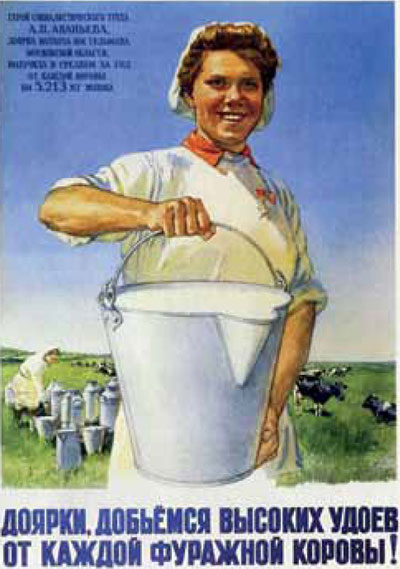

A. Ananieva, Hero of Socialist Labour, milkmaid at Telman Kolkhoz, Moscow Oblast.

Drew an average of 5.213 kg of milk from every cow over the year

Milkmaids! Get high milk yields from every forage-fed cow!

The slight liberalization of the late 1950s and early 1960s added a degree of “privacy” to personal life, gradually weakening the Bolshevik gender code and encouraging an alternative interpretation of femininity and masculinity in the USSR. At that point, the role of “shadow” gender contracts unregulated by the government grew stronger as a response to life in the soviet reality and the desire to conform to it.

In everyday life, women were expected to play their traditional role: to care for and serve the family, act as real and symbolic mothers, and perform functions that would compensate for the lack of relevant services and consumer goods. The USSR’s Constitution of 1977 enshrined an official family model with the woman at its center, defining the role of women in society as “hard-working mothers who raise their children and take care of the house.” Meanwhile, single mothers and women who were forced to have children by some circumstance grew more numerous, even if they did not fit into the official model of the family “as the central component of society.” This illegitimate gender model was constantly persecuted by the Communist government as something opposite to the “soviet lifestyle.”

Forced to find ways to survive during the stagnation of the Brezhnev era, women grew stronger as a gender element. A housewife’s social competence was measured by her ability to attain deficit food, provide clothes for the family, get a child enrolled in kindergarten or a good school, arrange for an experienced doctor to examine sick relatives, or welcome guests. The status of a soviet woman made her responsible, strong and capable of managing those under her care. This made men more infantile, unable to take part in the household routine or fulfill themselves socially. In the 1970-1980s, soviet films followed this trend, replacing soldiers and conquerors of virgin lands with unambitious researchers, humble engineers and half-hearted doctors, such as Zhenia Lukashyn in The Irony of Fate or Anatoliy Novosieltsev in the Office Romance.

Following the collapse of the USSR, gender relations evolved into a patriarchal renaissance of sorts. This transformation brought forth obsolete stereotypes of the woman’s role in family and society. Yet, despite structural changes and new gender practices, the rules, norms and traditions tracing back to soviet models of conduct are still palpable, confirmed among other things by employment statistics.

GLOSSARY

Etacratic gender model (from French état meaning the state and κράτος as power or strength in Old Greek) provides for tough government control over private life. Soviet authorities made women dependent on the state, effectively reflecting a patriarchal system of relations.