If you look at contemporary sociological surveys and identify the key issues bothering an average Ukrainian, the rule of law and construction or restoration of justice will be on top of the list. In fact, these have been priority concerns ever since humans began to unite in communities and conduct their affairs together. That was probably when the first need of certain norms of conduct appeared, which later evolved into the first legal codes known as customary law. In parallel, those who had to control it, take decisions and receive justice appeared.

Our traditional perception of medieval society builds on a number of stereotypes full of impunity of feudal lords, people in power and with weapons, thieves, attacks against homesteads, and robbery, but no norms, laws or courts. A nuanced look at these clichés in Ukrainian history shows a whole different picture.

We have similar stereotypes about ways to restore justice in the past. Even today, most professional historians in Ukraine have little notion of what the legal system was like in the Ukrainian territory in ancient times. But medieval and early modern history presents a quite capable legal system for its time, complete with various institutions and, most importantly, the ability of people to use these tools to meet their needs. The main thing for them was respect for what the modern world knows as the rule of law.

I had a chance to see how dominant such stereotypes are back in the 1990s when I was a student at the Pedagogic Institute in Kamianets-Podilsky, Western Ukraine. At one of the conferences there, a student of history spoke about the system of lawyers in courts across Ukrainian land in the 16-17th centuries. Aprofessor who had studied history in Leningrad in the early 1930s and had huge academic and teaching experience was very sceptical about the topic. “What lawyers could Ukraine possibly have in the 16th and 17th centuries?” was his reaction. After listening to the report, however, he had no choice but to accept its main points backed by references to the publicly available documents.

Ruska Pravda and its descendants

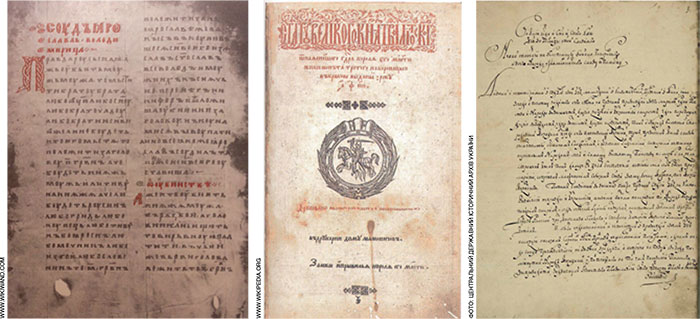

Given by Yaroslav the Wise to the Novgorod people in 1016, Ruska Pravda or the Law of Rus is conventionally believed to be the first written code of customary laws.Yaroslav’s descendants further completed it with Pravda Yaroslavovychiv, the Law of the Yaroslavychi, and an expanded version of Ruska Pravda. This relatively small code of legal norms ranging from 43 articles in its shorter version to 121 in the expanded one primarily described personal security and property rights. At that time, the evolution of legal thought in Ukrainian land walked hand in hand with that in its neighbors, the newly Christianized countries of Central Europe.

The late Middle Ages were the next stage when written codes spread across the territory, as a dynasty crisis erased from the political map of Europe the Kingdom of Halychyna-Volyn otherwise known as the Kingdom of Ruthenia, and part of the Ukrainian land, including Halychyna Rus and Western Podillia which ended up in the Kingdom of Poland, while Volyn, Kyiv region and Eastern Podillia found themselves in the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania. Each of these parts lived both by the indigenous legal norms, and by those imported from the West – primarily through the German-speaking residents of their cities. Quite a few educated people were there to enforce these norms after getting their degrees in well-known European universities of the time, including the University of Padua, a major center of legal education.

The old Rus tradition led to the borrowing of norms from Ruska Pravda in the part of Ukraine’s land within the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania for Casimir’s Code adopted in 1468 and the subsequent three Lithuanian Statutes of 1529, 1566 and 1588.The Statutes were based on the preceding legal acts but were enriched with the accomplishments of legal thought from the Renaissance Europe. They eventually became a foundation for legal relations in part of Ukrainian territory up until the 1840s when the Russian Empire abolished them.

Law and order. Every period of Ukraine’s history has its legal declaration. Kyiv Rus had Ruska Pravda, the Law of Rus. The Hetmanate had the 1710 Constitution

The Ukrainian lands that were integrated into the Kingdom of Poland fell under the jurisdiction of the crown law in 1434. To make it work in that territory, a network of courts was established. City courts led by a starosta, the king’s representative, thus dealt with criminal cases in the given territory. The land court dealt with the cases of the noblemen and others, other than criminals, settled in its jurisdiction. The nobility court solved the eternal problem of separating land between the noblemen. All posts in these courts were elected. Only starostas were appointed and dismissed by the king. While only the nobility could be elected as court judges, candidates still had to meet certain requirements. They had to be settled in the territory covered by the court’s jurisdiction, have integrity and authority in society. Clearly, that epoch did not have universal equality. But people saw election out of several candidates as a sufficient safeguard against corruption at that time.

Ukrainian cities started obtaining self-governance rights back in the early 14th century. These rights were given to them by supreme rulers. That approach to city governance was based on the 13th-century German models, initially granting Magdeburg and its residents the right to conduct their affairs independently. It was thus referred to as German or Magdeburg privilege. Historians still argue about which city in Ukrainian land was first to obtain it, listing Volodymyr, Sianok and Lviv, all in Western Ukraine, as options. This happened in the mid-14th century, the period of the Kingdom of Halychyna-Volyn. Therefore, most old Ukrainian cities have at least 500 years of local self-governance experience. Which is not too bad compared to the history of the land east of Poltava which is considered the easternmost city in Europe with a magistrate, a council, a burgomaster, municipal commissioners and jury panels – all the attributes a city needs to solve its affairs autonomously.

The language used by most legal institutions in Ukrainian land within the Kingdom of Poland was Latin. The few written documents preserved since that time and originating from the public chancellery, including international treaties and correspondence, were also in Latin. Polish failed to oust it even throughout the Age of Enlightenment.

The rest of Ukrainian land that was part of the Grand Dutchy of Lithuania used Ruthenian in recordkeeping. This privilege was cemented with the resolutions of the 1569 Union of Lublin whereby Volyn, Kyiv and Breslau voievodships went to the Kingdom of Poland. Courts used the Second Statute of Lithuanian with Ruthenian as the language of recordkeeping on this territory. Unfortunately, Polish began to slowly but firmly oust Ruthenian in recordkeeping in the 17th century, leaving titles of court cases as the only place for Ruthenian.

Parliamentarism and its traditions

In 1493, King Jan Oblracht convened the noblemen from all provinces of the Kingdom of Poland, including representatives of Ruthenian, Podil and Belz voievodships aristocracy, to initiate regular conventions of the Sejm, a parliament. It had two chambers. The upper chamber known as the Senate included voievods, castellans and Catholic bishops. The lower chamber, the Polish Izba, was comprised of elected deputies, i.e. the envoys elected in local sejms of the nobility. Having an active legislature allowed the noblemen to eventually organize into groups somewhat alike modern political factions. They tried to express the ideas they believed necessary for the country or their region in debates and speeches.

Any decisions taken at the conventions of parliament chambers had to be unanimously approved by all those present. Disagreement of one representative was a reason to close the convention and stop the work of the Sejm. At first glance, this unrealistic instrument in the democratic institution was an essential guarantee against corruption in which the king was always the main suspect. Interestingly, the first liberum veto, the voice of disagreement, came in 1652, over 150 eyars after the two-chamber parliamentstarted working on a regular basis.Further on, magnates and oligarchs took that effective instrument to often apply it in practice through dependant envoys. This led to a situation where most Sejm conventions never reached any logical conclusions or decisions because of the liberum veto abuse. That’s how democracy ended up ruining itself.

Local lawmaking. Rzeczpospolita produced its regional policies through local sejms

The crisis of the Jagiellonian dynasty in 1572 provoked a unique situation in Rzeczpospolita of which almost all Ukrainian lands were part by then. The Warsaw emergency Sejm in 1573 decided that every new king was to be elected by the general convention, the electoral sejm, comprised of all nobility in Rzeczpospolita. Europe of that time offers no examples of similar direct democracy, even if practised by the nobility only. Another important aspect of electing the new king was his personal pledge of allegiance to the people. Again, the people stood for the nobility. This simple procedure in Rzeczpospolita's political culture turned into an unbeatable barrier for Ukraine in Pereyaslav in 1654 when Moscow's ambassador Vasili Buturlin sharply refused to pledge allegiance to the Zaporizhian Army on behalf of the Russian tsar. The Cossacks were deeply familiar with the tradition of elected ruler and his personal allegiance to his subjects as a guarantee of their privileges. The Russian side did not understand or wish to understand this.

Mid-17th century developments provoked political separation of part of Ukrainian land from Rzeczpospolita. But they failed to make Ukrainians forget habits from back then – they were practised in many fields of life in the newly-established Hetmanate. It continued to use legal norms of the Second Lithuanian Statute and granted self-governance and Magdeburg-modelled to cities of the Left Bank Ukraine. Most offices in local administrations remained elected. An 18th-century attempt to codify laws in the Hetmanate to harmonise them with the laws of the Russian Empire was based on the Lithuanian Statutes, Sachsenspiegel and Kulm Law, another variation of rights for local self-governance in then-Central Europe.

The legal culture of the part of Ukrainian land which formed the Hetmanate after mid-17th century until the end of the 18th century was a mix of traditions from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania with its Second Lithuanian Statute, Rzezcpospolita with its elected officials and Magdeburg rights for cities, and Ukraine’s own traditions. A combination of these factors in the Left Bank Ukraine in the second half of the 17th century and throughout the 18th century shaped the Ukrainian notion of law which was rooted in the West through its concepts and traditions, but was implemented in practice in the East.

The clash of different cultures in practicing law manifested itself in the conflict between the Left Bank Hetman Ivan Briukhovetsky and Moscow ambassadors on the punishment for one of the Hetman's opponents. When they offered Briukhovetsky to punish the opponent for the second time, he referred to a basic norm of the Roman law which did not allow double punishment for the same crime.

The legal thought peaked in the Cossack Ukraine with the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk passed in Bendery in 1710. The text is full of fragments pointing to attempts of distancing from the legacy of Rzeczpospolita and finding an own place backed by the treaties from Bohdan Khmelnytsky's time. It also takes into account the sad experience of the Hetmanate in the late 17th and early 18th century. One example of this critical self-reflection is in a provision of the Constitution's Section 6: "… some Hetmans of the Zaporizhian Host took unlimited power, clamping down on equality and customs, and establishing the 'I rule how I wish' law. The atypical arbitrary rule in the Homeland and Zaporizhian Host resulted in divisions, distortion of rights and freedoms, oppression of people and forced unbalanced distribution of military posts. This fuelled disrespect for the general commanders, colonels and significant part of the community."

It is now difficult to speak about the likelihood of enforcing Orlyk’s Constitution in real life. But the mere fact of the Cossack leadership producing such a political legal document complete with the analysis of recent history deservers praise. The only thing is that this was not the first Constitution in the world or Europe, as many in Ukraine believe. Every successful Sejm convention in the Kingdom of Poland and Rzezcpospolita ended with the adoption of a constitution.

In the late 18th century, the Cossack hetmanate leadership began to “recollect” its origins in order to receive full aristocracy status in the Russian Empire. It took many families years to complete the process. However, the majority of coats of arms used by the Cossack nobility originated from Rzeczpospolita coat-of-arms associations with typical names, such as Lubicz, Leliwa, Jastrzębiec and many others rooted in the heraldry of the Kingdom of Poland since the 14th century. The sources for the heraldic symbols they adopted were in “…the Polish book Herbariusz which shows the coat of arms of the ancestor, and his entire family uses this coat of arms at its stamps till this day…”. This is a quote of an 1833 case to prove the noble ancestry of descendants of Fedor Mankovsky, a senior official with the Zaporizhian Host. Published in 1914 in St. Petersburg, the Armorial of Little Russiaby Vladislav Lukomsky and Vadim Modzalewsky features an exact copy of the nomenclature of coat of arms that senior dynasties in the Cossack state had used.

Regional self-governance

1572 marks the beginning of a triumph for democracy of the nobility on the regional scale. Local sejms become the place where all important affairs of the region – a voievodship, land or county — are solved. They present a platform for discussing state matters, including taxes, international politics, election of the next ruler and more; solving tax matters within the administrative region; and electing representatives of each territory in the central Sejm and judges of the Crown Tribunal, the supreme court of appeals based in Lublin since 1578. Also, they organize locally-funded territorial military units.

The elected nature of authorities, including the royal authority, made the life of Rzeczpospolita along with the Ukrainian land that was then part of it quite lively. It was difficult to forecast the outcome of elections which often turned into something close to battlefields where each party was willing to defend its interests to the very end. This seemingly perfect setup began to rot in the late 16th century as some families grew to dominate regionally, then on the nationwide scale, and to use any tools in their political activity to spread and strengthen their influence. Historians described this period the era of oligarchy. It led to the collapse of Rzeczpospolita.

One of the widespread stereotypes is to overstate the role of forays, the illegal ways to solve conflicts. But a closer look at the actual forays shows that the modern notion of the number of participants and victims in them is exaggerated. Forays were rather a gesture or a call of reconciliation or dialogue to the other side. Nobody in their sound mind wanted to shed blood for no reason. Even some powerful actors, such as Kostanty Ostrogski with his unlimited financial and human resources to implement his interests, had to respond to the numerous lawsuits in courts like any average person. More importantly, they did not always win those lawsuits. Even an average individual had a chance to win a case and get justice, although the path to that justice was very long and difficult.

Given this long-standing tradition of justice done in courts and regulated by a written code, the Russian Empire was forced to preserve that old system and traditions in justice on the Ukrainian land for many years after the 1793 and 1795 divides of Rzeczpospolita. Regional courts in the Right Bank gubernias were a continuation of sorts of land and city courts from before where anyone could file a lawsuit about their case. These courts also issued a huge number of documents. In this case, court records were a notarial and legitimizing institution while every document with a copy included in the court records was equal to the original act in status.

Civil law

This widespread network of institutions encouraged the evolution of a tradition to use them. As a result, regional and city courts were stormed with numerous lawsuits after the Hetmanate was abolished in the Left Bank Ukraine and the Right Bank Ukraine was integrated into the Russian Empire in the late 18th century.

The tradition of solving matters in courts went back to the 15th century in Ukrainian land. A typical case in point was the testaments not only for the richest nobility, but for the average residents in Ukrainian cities. Kyivites recorded their last will with eyewitnesses and appointed those responsible for implementing the testament since the late 16th century, even if Kyiv was in the far east of Rzeczpospolita. In Lviv, this practice was so widespread that the testament and after-death inventory records from Lviv residents in the 17-18th centuries were comprised of many hundreds of documents.

As several ethnic communities lived side by side in then-Lviv or Kamianets, they shaped solid criteria for different jurisdictions. For example, any violation involving a person belonging to different jurisdictions – as in a fight between a Ruthenian and a Pole in an Armenian pub – required the establishment of a joint commission to determine the guilty and the punishment.

The rule of law and multiple legal institutions in Ukrainian land made a system of viable legal norms for all citizens established on this territory through a fusion of local traditions and legal norms from the Old Rus time, and the practices borrowed from the West. These norms were effective on this territory for almost 500 years.

The soviet authorities wiped out the notion of getting justice through legal and parliamentary instruments in the 20th century. Reality on the ground in modern independent Ukraine demonstrates disrespect and inability of the state to guarantee equal rights to all of its citizens.

By Vitaliy Mykhailovskiy

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook