There are two distinct ways to create myths: suppressing an inconvenient truth and imposing a patent untruth or half-truth on society by dictating how something should be remembered. Both methods have been employed in creating the myth of the “Great Patriotic War”. For starters, Stalin’s ideologues completely excised the period of the Stalin-Hitler pact and the tragic year of 1941 from the living memory of society. Soviet myth-makers later spared no expense on bronze and glitter in adding them to the real and pyrrhic victories of the Red Army.

As far as Ukraine’s “liberation” from the German occupation is concerned, there were, from the viewpoint of the Soviet authorities, weighty reasons to “revise” this utterly complicated and controversial historical episode. The return of the Red Army was accompanied by “purges of collaborationists” and an overall mobilization of the local population, which Soviet generals used as veritable “cannon fodder”. Another problem for Stalin’s regime was the fight against the national liberation struggle in Western Ukraine, which peaked precisely during this period and continued until the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Therefore, for a large part of the Ukrainian population, Stalin’s “liberation from the Germans” was a mirror image of Hitler’s “liberation of Ukraine from the Bolsheviks” – providing freedom without liberation.

THE REVENGE OF THE LIBERATORS

The Nazi occupation instilled terror and hatred in nearly all strata of the Ukrainian population. Still, despite the overall negative attitude towards the Germans, the return of Stalinism was perceived quite ambiguously in Ukraine. To residents of eastern Ukrainian cities, who had suffered more than others during the occupation and whom the Nazi policy essentially doomed to slow extinction, the return of the Soviet authorities spelled a revived hope for life. Even the role of a “cog” in Stalin’s totalitarian system was much more appealing than the prospect of forever being a German slave and Untermensch—a member of a “lower race”. The arrival of the communist authorities extended the hope of stable employment and pay, a certain, peculiarly Soviet kind of welfare (rations, aid to the families of war veterans, healthcare, etc.) and thus the restoration of the ordinary Soviet way of life, which had almost been forgotten during the time of occupation.

Let’s give more bread to the front and the country!

On the other hand, a large part of the population was apprehensive of revenge on the part of Stalin’s regime. There were a number of Ukrainians who had actively or passively cooperated with the Germans. Apart from those who served in the German police and Wehrmacht, the Soviet authorities targeted various local chiefs (primarily, village heads) and even street sweepers who had made lists of communists and Jews for the Germans. At the time, hundreds of thousands of men who had deserted from the Red Army in 1941 and women who had had sexual contact with Germans were awaiting their hour of reckoning. Also suspect were Communist Party members who had remained in the occupied territory but had not joined partisan units, as well as entire ethnic groups and even peoples, such as the Crimean Tatars. In fact, everyone who had not actively fought against the Germans could be viewed as “guilty” by Stalin’s regime.

At the same time, in order to survive in occupied Ukraine people had to contact or cooperate with the enemy in one way or another. Everyone did it in his own fashion. The methods of “cooperation” were numerous – from service in German administrative or economic institutions, the police, or Wehrmacht, to employment in factories or agriculture, paying taxes to the Germans, and so on. It should be noted that over 90% of Ukraine’s population remained in the occupied territory, including a high proportion of intellectuals, primarily in technical fields, such as engineers who helped the Germans put factories back into operation after the Red Army retreated in panic in 1941. With their help, the Germans were able to restore functionality to the Donbas coalmines, many of which the Bolsheviks had blown up during their retreat. The Germans, of course, made full use of Ukraine’s agricultural sector and its abundant output.

Therefore, it is no surprise that after nearly two years of German occupation, Stalin’s authorities considered the entire Ukrainian population guilty of having “connections” with the enemy. On 7 February 1944, at the 9th Plenum of Soviet Writers in Moscow, writer Petro Panch put it into words, stating: “The entire population that is now found in the liberated regions cannot, in essence, openly look in the eyes of our liberators, because it has become entangled in connections with the Germans to some extent. … Some plundered flats and offices, others helped the Germans in looting and shooting, still others profiteered and engaged in commerce, while some girls, having lost a sense of patriotism, cohabited with the Germans.”

Later on, everyone who had remained in the occupied territory was declared suspicious. This was officially manifested in the infamous query on the typical Soviet questionnaire: “Have you or your relatives been in the occupied territory?” According to some recently declassified information, more than 320,000 Soviet citizens were arrested in the USSR in 1943-53 on charges of cooperation with the Germans. In Ukraine, this number was 93,690 for the period of 1943-57. More than half of these people were from Western Ukraine and were often punished primarily for nationalist activities (“Ukrainian-German bourgeois nationalism”), which the communist authorities invariably associated with “collaboration”.

The residents of Sloboda Ukraine (Slobozhanshchyna) and the Donbas were the first to experience the fury and hatred of the “liberators” towards those “who had served the Germans”. A report by a Müller, representative of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, said, among other things, that the NKVD carried out mass arrests in the Sloviansk-Barvinkove-Kramatorsk-Kostiantynivka sector the day after the Red Army entered the area in spring 1943. The repressive blow targeted those who had served in the police, worked in German administration or economic services, as well as girls who had been translators or had some other contacts with German soldiers. Women who had had sexual contact with Germans (were pregnant or had children from Germans) were immediately killed together with their children. A total of some 4,000 people were shot.

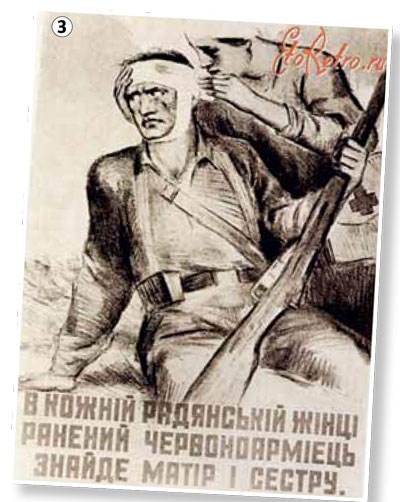

An injured Red Army soldier will find a mother and a sister in every soviet woman

In some places, women were among the first targets of revenge by the returning Red Army. Oleksandr Dovzhenko wrote in his diaries about fairly frequent cases when women were shot for “treason”, a common occurrence in the period of “liberation”. Whether the greatest motivation for this was sadism on sexual grounds or the “noble” patriotic indignation of slighted men remains a matter of contention. Otherwise it would be hard to understand the motivation of a Soviet general who personally shot teenage girls in cold blood, deeming them “traitors to the Fatherland”, right after interrogating them about their intimate affairs. A number of women were shot near Melitopol in autumn 1943. These events prompted Dovzhenko to include in his famous film Ukraina v ohni (Ukraine in Flames) an image of a woman who “slept with an Italian officer” and was later killed by partisans for doing so.

Kyiv resident Hanna Dziubenkivna testified about searches and repressions that swept across Kyiv after the Red Army returned. Special boxes were hung on walls in which citizens were supposed to deposit their denunciations of those who had “served the Germans”. NKVD men came to her place to search it. The woman had washed dishes in a German cafeteria, so she was accused of cooperation with the Fascists. They found copies of Adler, a German magazine, in her home and arrested her, even though she could not read in German.

A CRISIS OF LOYALTY

However, the main problem for the returning regime was not so much to exact revenge on “traitors” as to restore the operation of the Soviet administration, because neither local councils nor party bodies were functioning. This soon proved to be quite a challenge, primarily due to the lack of a loyal and faithful cadre. British military correspondent Alexander Werth was surprised that upon “liberating” Ukrainian cities the Red Army would appoint Russians, rather than Ukrainians as heads of local city councils. “Does the army want to see ‘sincere Russians’ rather than Ukrainians in high administrative positions in Ukrainian cities soon after they are liberated, because ethnic Ukrainians could be more tolerant towards the local population? Was it an accident that Russians were to become mayors in Uman, as previously in Kharkiv and later in Odesa?”

Local communists who had endured the hardships of partisan and underground struggle against the enemy were supposed to comprise the core of the restored communist authorities. However, it turned out that a majority of Ukrainians had not only failed to fight the Germans but also collaborated with them in some areas. A total of 142,134 communists—over 25% of the Communist Party of Ukraine—had remained in the occupied part of Ukraine of which 113,890 survived the occupation unharmed. Many communists and Komsomol members registered with the Gestapo for checks. For example, an NKVD report says that a large number of members and candidate members of the Communist Party as well as Komsomol members legally resided in the temporarily occupied territory of Voroshylovgrad Oblast (present-day Luhansk Oblast). In Voroshylovgrad alone, 750 such communists and 350 Komsomol members were registered as of 15 April 1943.

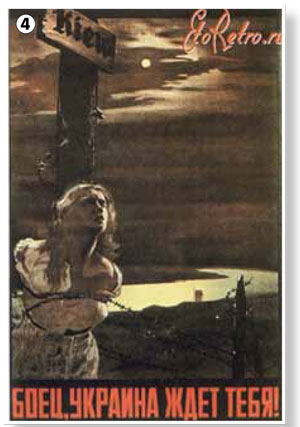

Soldier, Ukraine is waiting for you!

Therefore, just like other segments of the Ukrainian population, most communists found themselves in the “suspicious” category and for a long time were scrutinized by the party and other bodies. The Communist Party of Ukraine periodically underwent purges, and its revival took many years – until freshly initiated communists returned home from the army and the flow of party and administrative cadre from Russia resumed.

“MAY THIS THING PASS AND THAT THING NEVER RETURN”

Ukrainian peasants were also concerned about the restoration of Stalin’s regime, primarily because the old collective farm system could be reinstated. Such attitudes were, to an extent, expressed in a saying that was popular in rural areas in early 1943. It said of the Germans and the Bolsheviks: “May this thing pass and that thing never return.”

The Ukrainian farmer viewed the return of the Red Army with reservation. “It was impossible to conceal the passive attitude of Ukrainians to the war and Soviet victories,” Milovan Dilas recalled. “The population made an impression of gloomy concealment and paid no attention to us. Even though officers – the only people we had contact with – were silent or spoke in exaggeratedly optimistic tones about the attitudes of Ukrainians, the Russian driver lambasted them, using obscene language, for having fought so poorly that the Russians had to liberate them now.” The Yugoslav communist also mentioned that the secretary of the Uman district party committee was annoyed by the passivity of the locals during the occupation because the partisan unit he had led had so few people that it could not even handle the pro-German Ukrainian police.

That the comeback of the Soviets, or the “Reds”, did not arouse much enthusiasm in Uman in spring 1944 was also noted by Werth: “The locals seemed to be quite indifferent to what was happening.” Major Kampov (the real name of writer Boris Polevoy) tried to explain to the foreigner why the peasants were so indifferent towards the Soviet authorities by appealing to the consequences of the German occupation that had “demoralized many people in this part of the country”. “And even though they hate the Germans, they have largely lost the sense of socialist consciousness and have become narrow in their worldview,” he said. On hearing this, the British correspondent ironically said to himself: “They will have to work hard to instil the right sense of Soviet consciousness in these people.”

Their conversation also touched upon collective farms and the attitude of Ukrainian peasants to them. “They had a pretty good life here during the occupation because the cunning Ukrainian peasant is the world’s best specialist in concealing foodstuffs,” Polevoy said, relating an opinion that was popular among the Soviet party elite. “They had always hidden food from us, and you can imagine what a great job they did under the Germans. Now that the Germans have disappointed them by promising them land and not making good on their promise, they probably hope that we will scrap collective farms, but we won’t.”

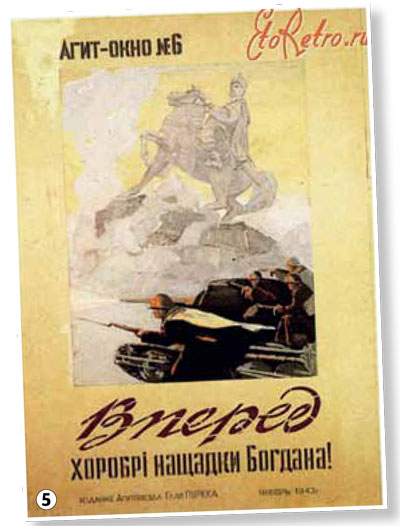

Forward, Bohdan’s courageous descendants!

MOBILIZATION AS AN ACT OF REVENGE

Another important factor that made the Ukrainian population pessimistic about being liberated from the Germans was the Soviet military mobilization. The ways in which it was administered turned out to be utterly strict, if not cruel. The reason was that it involved the active army, which had been given carte blanche to use local human resources to meet its needs, with virtually no restrictions.

Indeed, frontline military enlistment offices made the drafting process much faster, but the quality of selection and the training of the mobilized were substandard. Age-related, medical and other restrictions were violated in the process. The biggest problem was the short duration of military training. In the long run, it reflected negatively on the combat capacity of Soviet troops. Following the Red Army’s return to Ukraine, it became more a rule than an exception to send poorly armed soldiers with little or no military training into battle. Thus, while the soviets claimed to be giving Ukrainians a chance to avenge themselves against the Germans, this looked more like revenge exacted on those who had been under enemy occupation. In fact, even the Germans could not understand why the Ukrainian population was treated this way. After studying captive Red Army men at the time, the Germans reached a paradoxical conclusion: the Soviet Union had completely exhausted its human resources – they found a number of local teenagers and elderly people who had been mobilized several months before their capture.

Ukrainian émigré writer Mykhailo Doroshenko described in his memoirs how the Red Army had driven people without weapons into action in his native Kirovohrad Oblast. They were ordered to obtain weapons for themselves as they engaged in battle with the enemy. Political instructors and commanders would tell them: “Through these efforts and through your blood you must wash away your sin before the Fatherland and its great chief Stalin.”

Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s diaries also bear witness to the concerns Soviet Ukrainian intellectuals had about mobilization. For example, in spring 1943, he wrote down a story told by writer Viktor Shklovsky that great numbers of men mobilized in Ukraine were dying in action. They were called chornosvytky for having no military uniform and wearing their civilian clothes. They had no military training and were treated as offenders. One general watched them in action and wept… “Everyone is tormented by the thought of the inhuman, unheard-of sufferings of these people,” Dovzhenko wrote after meeting several of his acquaintances. “They say that [the Reds] start preparing 16-year-olds for mobilization, that poorly trained men are being sent into battle as offenders and that no-one feels sorry for them. How horrible it is to think that Ukraine may be left without any people after this – 19-year-old girls are already being enlisted, and many more have been destroyed or driven to damned Germany by Hitler.”

In general, 2.7-3 million people were mobilized to the Red Army in Ukraine, i.e., about 10% of the population. This points to general mobilization. In some oblasts of Western Ukraine where over 15% of the population were drafted, it was a matter of total mobilization.

All of these circumstances were significant factors that led to a situation in which Ukrainian losses during the “liberation” period were disproportionately higher than during the Nazi invasion of 1941.