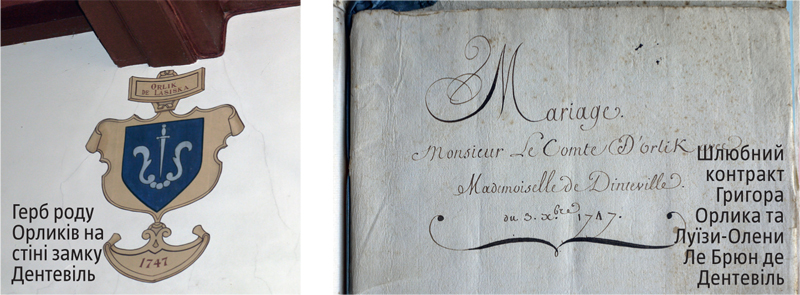

Château de Dinteville, a castle in the French province Champagne-Ardenne, was once home to Hryhir (or Grégoire) Orlyk, a French diplomat and the son of the well-known Hetman Pylyp Orlyk who, serving as Hetman of Ukrainian Cossacks, wrote the Pacts and Constitutions of Rights and Freedoms of the Zaporizhian Sich in 1710. This was a unique document in that historic period, often referred to as one of the earliest constitutions in Europe. The coat of arms of the Orlyk family, the marriage contract between Hryhir and Louise-Hélène Le Brun de Dinteville, a pile of yellow 18th-century papers… These have been passed from one generation to another in the family of the castle’s owners, marquises de la Ville Baugé.

Time seems to standstill in this building. Old walls that built back in the 13th century had since witnessed peasant revolts, the French bourgeois revolution and two devastating world wars. But the foundation of Dinteville must have been laid under a lucky star. “The castle suffered almost no damage,” marquise Antoinette de la Ville Baugé tells The Ukrainian Week. “Hryhir Orlyk, when he came here to get a break from military campaigns, saw virtually the same things you can see today – the same towers, gates, alleys and walls.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukrainian State and Elites in the Early Modern Era

Her husband, Henri de la Ville Baugé, a distant relative and heir of the Orlyks adds: “Our castle did not have strategic military importance, even though it was built in a place where a fortress once stood. Village Dinteville nearby had up to 300 people at the best of times. Now, there are some 60 permanent residents here. In the revolution and during the two world wars, several doors and a wardrobe were broken here and that was it. The archives have been fully preserved, including a rope-bound package with the papers of Hryhir and his wife.”

Godfathered by Ivan Mazepa, Cossack Hetman and patron of arts and education, and godmothered by the wife of General Judge Vasyl Kochubei, then awarded the Order of Saint Louis, the Swedish military Order of the Sword and the Polish Order of the White Eagle, Hryhir Orlyk spent his first years as émigré in the court of the Swedish monarch with his father, and served in the Swedish and Saxon royal guards. After the death of Charles XII, the Ukrainian political émigrés were no longer welcome in Stockholm. The Orlyk family moved to Poland, and Hryhir’s father, Pylyp Orlyk travelled from there to Turkey, while Hryhir served in the Saxon and French royal courts and later as a royal diplomat. He was dispatched to the Crimean khan, Turkish sultan and other rulers. His most glorious mission was probably the restoration of King Stanisław Leszczyński on the Polish throne in 1733.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Cross Versus the Crescent Moon

"At a time when one’s background was all important, he managed to make a brilliant diplomatic career exclusively owing to his ability,” Iryna Dmytrychyn, author of the book Grégoire Orlyk – Un Cosaque ukrainien au service de Louis XV (Hryhir Orlyk, a Ukrainian Cossack in the Service of Louis XV) published by L’Harmattan, explains: “In the hierarchical society of the time, Hryhir Orlyk, an exile and émigré, talked with ministers and kings, engaged in big politics and constantly, sometimes openly and at other times obliquely, reminded of the ‘yoke under which the Cossack nation was groaning’. Hryhir Orlyk was a lone warrior in the field, a man who strove for the ‘freedom of the Cossack nation’ for the sake of peace in Europe.”

Antoinette and Henri de la Ville Baugé, owners of the castle and heirs of the Orlyk archive

The French king sent Orlyk, his special-purpose diplomat, on secret missions that could easily make a good plot for a suspense film. He had to disguise himself as a merchant and doctor, a servant and pilgrim. “My grandfather and father spoke a lot about him,” Henri de la Ville Baugé recollects. “He was a kind of mythical figure. But we knew very little about him. He was not French and did not belong to dynasties known at the time… His mission of a secret agent in the royal service must have been the only way for him to survive.”

No-one knows what Hryhir Orlyk actually looked like. No authentic portrait of him has survived. The documents written in hand by the legendary Ukrainian are almost all in French. The only Ukrainian-language document is a christening certificate. The majority of papers are draft letters which Orlyk sent out to governments across the world. In a letter to cardinal André-Hercule de Fleury written in 1741, he defended the “undeniable right of the Cossack nation to Ukraine which has been usurped by the Russians. This nation has been denied its privileges and freedoms and the yoke imposed on it is becoming increasingly unbearable.” Another of his documents noted: “The common interests that Sweden has with the Kingdom of Poland and the Ottoman Empire, the benefit they have already been able to receive from cooperation with the Cossack nation and the presently conducive conditions convince me that my father could not have hoped for a better opportunity to again show his loyalty to Your Highness and other rulers who would want to see Russia weakened.”

RELATED ARTICLE: The Battle of Batih Won Independence for Cossack Ukraine in 1652

Orlyk was constantly on the move, either in military expeditions or on secret missions, and thus remained a bachelor for a long time. He married Louise-Hélène Le Brun de Dinteville in 1747 at the age of 45. He then lived out the last 12 years of his life at Château de Dinteville. The couple did not have children. “The marriage with Madame de Dinteville allowed him to settle down and was probably prearranged,” Ms. Dmytrychyn suggests.

The current castle owners remember several Ukrainian researchers who have taken interest in Hryhir Orlyk. “Historians Illia Borshchak and Orest Subtelny, as well as writer Anna Shevchenko, have worked with the archive,” the marquis says. “They all hoped to find Vyvidprav Ukrainy (The Genesis of Ukraine’s Rights, a manifest allegedly written by Pylyp Orlyk, addressing European monarchs and focusing on facts confirming the sovereignty of the Ukrainian Cossack State based on international treaties, the need to restore Ukraine’s sovereignty and the benefits of democracy over despotism. The original version of the document was never found – Ed.) which, according to Borshchak’s version, Orlyk sent out to the leaders of European states. No-one has been fortunate to find this document.”

Left: Orlyks’ coast of arms on a wall in the Dinteville Castle

Right: Marriage contract between Hryhir Orlyk and Louise-Hélène Le Brun de Dinteville

“The activities of Hryhir Orlyk prove that an understanding that the Ukrainian Hetman lands were part of the Western civilization, rather than the ‘barbarian’ East, was the norm in the 18th century,” says Ms. Dmytrychyn, whose book Hryhir Orlyk, abo Kozatska natsiia u frantsuzkiy dyplomatii (Hryhir Orlyk, or the Cossack Nation in French Diplomacy) will be published by the Tempora publishing house in 2014 in Ukraine. “Personally, I am moved by the fact that he fought in hopeless conditions. He could not fail to understand the futility of his efforts! However, as Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, one of the best characters in French literature, said, to fight knowing that you will not achieve your goal is even nobler. You cannot choose to fight only when you are certain of your success. You should always fight for your ideals and ideas if you know they are right. To me, Hryhir Orlyk impersonates an ability to defend your convictions regardless of the circumstances. He deserves our respect, and his name is worthy of being remembered by future generations. This is one of the bright figures in Ukrainian history.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Where Did “Ukraine” Come From?