In July 2018, before the presidential campaign kicked off officially, the impression was that socio-economic indicators would play a serious role in the race. Ukrainian politicians were undergoing a serious crisis of ideas. Nobody could offer new solutions to the key issues of war and peace, so the only path to the hearts of the voters was through their wallets.

SOCIS, a pollster close to Petro Poroshenko, did a survey about the subsistence level, wages and pensions Ukrainians wanted. The numbers were UAH 6,659, UAH 11,951 and UAH 7,451 respectively. The real numbers, according to the State Statistics Bureau, were UAH 1,777, UAH 8,725 and UAH 2,479. The Ukrainian Week wrote that decreasing the gap between the income Ukrainians wanted and had in reality would help those in power stay.

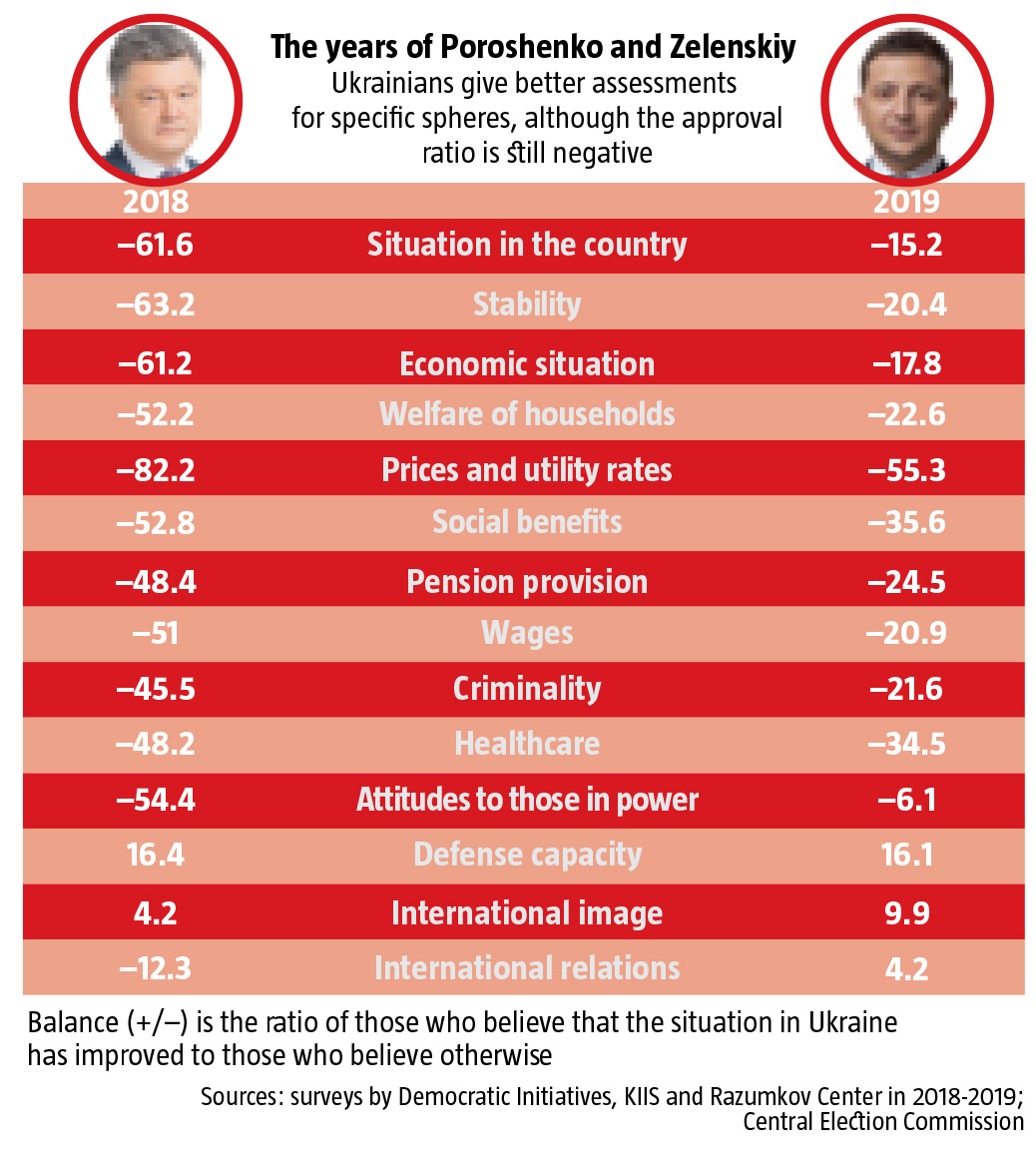

That forecast was accurate only partly. Indeed, the elections never grew into a competition of ideas: the victorious Volodymyr Zelenskiy stood out for not saying anything throughout the campaign. His rate of recognition and no experience in politics guaranteed his leadership in polls. However, the previous government failed to improve social standards significantly. At the end of 2018, frustration with all spheres of social life dropped somewhat but remained very high, leaving the government with barely any chance of victory. According to the end-of-year survey by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, the balance in the evaluation of changes in the pension system was at -48% and of salaries at -51% (the gap between those who saw changes for the better and worse). These indicators were self-explanatory: the gap between what people wanted and had was huge indeed.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ze Nation

We are now in January 2020. The average pension was UAH 3,016 in October 1, 2019, and salary – UAH 10,679, while subsistence level climbed to UAH 2,027 by January 1. These figures are far from what Ukrainians wanted in July 2018. Yet, the survey by the Democratic Initiatives and Razumkov Center showed a surprise – or a miracle. The assessment of pensions is still negative, but it improved twofold over 2019 rising to -24.5%. The assessment of salaries is at -20.9%, and the dynamics is similar for all other sectors covered by the survey (see The years of Poroshenko and Zelenskiy).

A closer look at the latest figures shows that the number of people convinced that their income has increased is not that high. Far more respondents think that the situation did not change throughout in 2019. Before, all these people said that the situation deteriorated, even if there were no objective reasons for that.

It is difficult to explain this psychological phenomenon at first sight. The pollsters claim that this reflects an advance of trust given to every new government. “This reflects a trend whereby a change of government boosts the level of optimism at the very least. Still, positive assessments prevail over the negative ones in just three areas: defense capacity, Ukraine’s international image and international relations,” explains Andriy Bychenko, Director of Razumkov Center’s sociology section.

Expectations about the future have always been positive rather than negative in Ukraine. Despite many problems and complaints about life voiced everywhere, Ukrainians are definitely not a pessimistic nation. When citizens think of Ukraine’s future, optimism and hope prevail. This has been the trend for several years now. The sense of anxiety comes third in that list. The three top emotions did not changed in 2019 survey, yet hope and optimism strengthened their positions by 4% and 8% compared to 2018, while the level of anxiety dropped to 7%.

RELATED ARTICLE: Unitarity under assault

According to annual surveys, Ukrainian citizens feel happy rather than anything despite any developments around them. The number of the happy citizen increased in 2019 too in all regions except for Central Ukraine where the figure dropped by several percentage points. Despite this improvement of assessments in different spheres, sociologists warn against far-reaching conclusions – they saw similar trends in 2005 and 2014. “The ball is now in the government’s court. There is some social optimism and that can help those in power do changes in the country,” Bychenko adds.

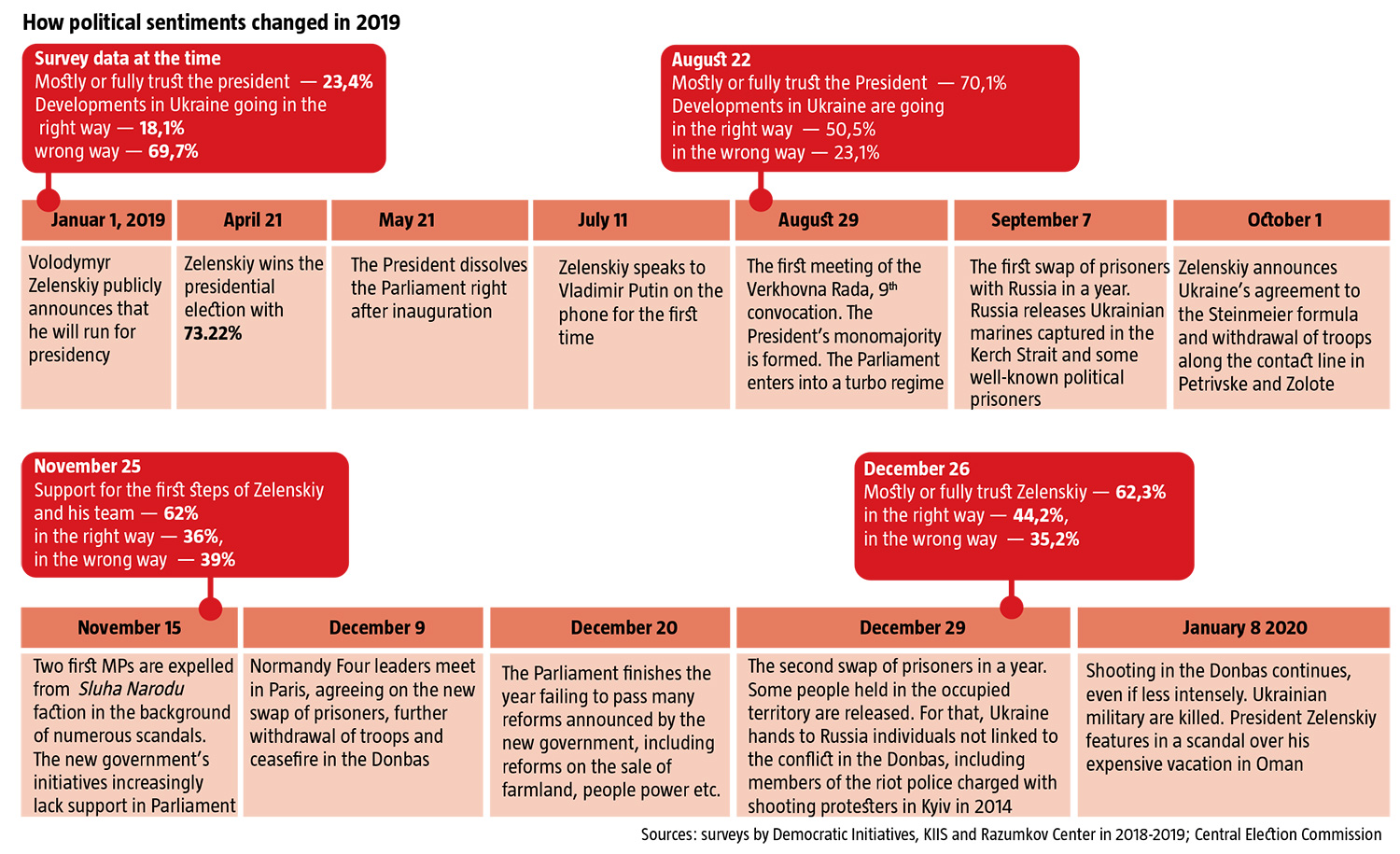

There is one thing in which the current government has beaten its predecessors. While Ukrainians used to lose their hope in the new leaders after half a year before, most still believe that Ukraine is on the right track now. Trust for the President remains high at over 60%. In terms of the approval rating, President Zelenskiy has almost caught up with the Armed Forces, the Church and volunteers, the three most trusted institutions in Ukraine.

This is where good news for the current government ends and the worrying ones start: inflated expectations come hand in hand with inflated responsibility. While Zelenskiy kept silence during the presidential campaign, some of his few promises are firmly in the minds of his voters. The top ones are about “putting people in jail in spring” and the new Government’s declarations of 40% economic growth in five years. Another irritant is the end of war which President Zelenskiy pledged to accomplish, including through talks “with devil if need be.” So far, prisons are not full of top corruptioners, economic growth has not sped up, prices are not falling and shooting in the Donbas continues.

The threat of frustration is far closer than it seems. Even though President Zelenskiy is still enjoying a sexy approval rate, his major allies are mostly in negative ratings by now. His Chief of Staff Andriy Bohdan has -32.7%, Servant of the People faction head David Arakhamia has -32.6% and Prime Minister Oleksiy Honcharuk is at -16.1%. Parliament Speaker Dmytro Razumkov stays at 10%, but that is seven points below what he had two months ago.

President Zelenskiy has managed to delay social frustration with his office with memorable events where he features as protagonist. One was the Normandy Four meeting in Paris in early December 2019 and the release of Ukrainian war hostages. Avoiding a new gas war with Russia helped too. These events were impressive enough to overshadow negative developments, such as the price Ukraine paid for the release of its hostages. According to the survey by the Democratic Initiatives and the Razumkov Center, Ukrainians listed presidential and parliamentary elections, the release of hostages and the Normandy Four meeting in Paris as the top events of 2019. Almost 60% of those surveyed thought that the main development of the year was positive and 10% thought the opposite.

A closer look reveals that elections are the only developments of domestic policy. The rest are international affairs. In its first six months in power, Zelenskiy’s team has not done a single noticeable step towards changing the system domestically. Even if the trends acceptable to Zelenskiy continue, foreign policy cannot patch up the gaps in domestic policies forever. People will return to their wallets sooner or later and start talking about their aspiration of fairness or justice. When that happens, Zelenskiy will have just two cards in his sleeve: a change of Government and possible snap parliamentary elections.

Petro Poroshenko used the first trick to temporarily channel popular frustration against the first premier under his presidency, Arseniy Yatseniuk. He left his office with the approval rating of below -80%. The second option is only possible if Zelenskiy himself retains a good rating in the next six months. A third option is to launch full-scale reforms and to accomplish fast economic growth as Zelenskiy promised. Yet, given Zelenskiy’s attempts to act as a Ukrainian Lukashenka who gives personal orders to everyone instead of conducting systemic transformations, this seems increasingly unlikely.

RELATED ARTICLE: Imitating deoccupation

Another question remains on the table among government watchers. “I’d like to assure you now: I’m going for one term to change the system for the future,” is the quote from Zelenskiy’s campaign platform. His first six months in power were obviously aimed at keeping his popularity high. Why does he need that if he does not plan to re-run for office? The goal could be to use social trust to make the implementation of reforms easier. 2020 will give the answer to that.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook