“Who can say on the spot what his grandparents' first and last names were as well as when and where they were born?” asks Natalia, a museum worker and guide in Kharkiv, addressing students visiting on excursions. The results are stunningly poor: genealogy is not encouraged in Ukrainian families, even though the number of people wanting to delve into the history of their families has skyrocketed in the past 20 years. “Until the early 1990s, virtually no-one took any interest in genealogy,” says Natalia. Now, she says, there is a boom in Ukraine.

Digging into archives

“People of all walks of life come to us,” she says. “Folks want to learn about more than just where their ancestors came from – they’re interested in everything. What did they die of? Did they have any hereditary diseases? Were they good-looking, rich, enterprising? What nationality were they? What did they achieve? The archives are crowded with students of family history.”

“The central documents in genealogical studies are birth registers, which contain records also of baptisms, marriages, and deaths,” says Tetiana Liuta, head of a history research lab at Kyivan Mohyla Academy. “Widely available Orthodox sources of family history reach back to the mid-18th century, while Greek Catholic and Catholic reach even further, to the 17th century. Despite some losses, the bulk of birth registers have survived. For example, the Poltava region suffered greatly during the Second World War, but records in the Kyiv and Chernihiv regions have been preserved fairly well. Moreover, there are also confession records and audits, which also provide information to be studied. Everyone has a chance to learn about his or her ancestors. However, this tedious work requires perseverance and great will.”

The relationships between amateur genealogists and archives are overshadowed by mutual reproaches. “We have very limited access to archives due to the tradition of keeping information closed. It is very problematic to study records carried out in Kyiv. I have been trying for many years to obtain these data from the old archives but there are problems with the way they are kept,” says Ms. Liuta. Archive employees explain that it is the lack of adequate technical equipment that prevents them from making life easier for researchers. “Documents are unique — we have one copy only. A church could keep a birth register for a decade, which means that it will sometimes have 1,500-3,000 pages. A technical archive employee has to count every page in the book and check the wax seals before and after you study it. Therefore, the archive is technically unable to provide people with these materials. The researchers are unhappy, but we can’t help it. And we don't have money to scan or digitize materials. We lack an NGO that would establish cooperation with the archive and accumulate and analyze genealogical information," says Ms. Liuta.

Generational links

"When you come to the cemetery to see your relatives’ graves and begin to read the last names on the tombstones, you realize that you belong to a family that has been around since time immemorial," says Kyivite Maryna Senchylo as she remembers how she became keen on genealogy. "Then my grandmother started telling me things that she had not spoken about before: the famine, the war, and how it all happened in reality, without overly emotional language. I realized that it was not so unambiguous as it seemed and that I needed to study it."

Genealogy research usually begins with one’s own family. First one gathers together all the documents that can be found at home: birth, marriage, and death certificates. It is also important to talk to relatives about the dates and places of birth of one's ancestors and their interpretations of photos and memories. “I was interested why the birth certificate of my great-grandmother did not fit in with what my grandmother told me,” says Maryna. “The document I found was issued in Berezniaky, Cherkasy oblast, while my grandmother told me that as a child she played with a birth certificate which bore a two-headed eagle and said that Yekaterinoslav was her place of birth. This is how I learned that my great-grandmother was really born in Dnipropetrovsk, but this had yet to be proven.”

Once information has been collected within the family, the search must continue in sources. These include not only the wide network of both Ukrainian and foreign archives from which certain information can be obtained by correspondence, but also the offices of military draft commissions and the Red Cross. Finding evidence to confirm her finding turned out to be a challenge for Maryna. To put it simply, it was too expensive. “My great-grandmother was born in 1900. At the time, there were about 14 churches in Yekaterinoslav, according to different sources. In order to find the date of her birth, one would need to look through all of their birth registers. If professional genealogists are commissioned to do the work, it won’t come cheap — $20 per book — but will save you time. Alternatively, I can make an official request to the archive for about UAH 186, but to do so I would have to present documentary proof of my relation to the great-grandmother. Unfortunately, none has survived.”

Internet resources can also be tapped into. Web portals on genealogy will help you with their detailed description of search possibilities and snags in this endless process. If your relatives died in the First World War, went missing in the Second World War, or were repressed or sent to labor camps, each category needs to be looked for in a different place.

Ihor Rozkladai, lawyer and moderator of the Rodovid genealogical portal, studied his family line nine generations back. “It all began in 2007 with an inquiry I sent to the Central State Historical Archive in Kyiv about my great-grandmother,” says Ihor. “Our first shock came when we learned that we had the wrong date for her birth. Since then, I have been researching in the archives, for the most part remotely.” In three years Ihor spent around UAH 3,000 on his research, not including the cost of travel. But considering that private firms will charge you UAH 500 for information about one person, Ihor saved significant money – his family tree includes over 300 people.

“Genealogy is a re-interpretation of history,” says Ihor. “What is taught in school is shallow history that gives you some general ideas about what happened. When you begin to study all of this at the microlevel, you can understand, if not justify, why people acted the way they did. Genealogy should be taught in senior classes; this would encourage school students to take an interest in history as such.”

A Mazepa family

“A man by the name of Mazepa once contacted me wanting to reconstruct his family tree,” says Ms. Liuta. “I filled out an application form and went first to the archives in Rivne and Zhytomyr oblasts and then to Tesluhiv, near Berestechko in Volyn oblast, where I found the bulk of the relevant birth registers.” As she talks, Ihor Mazepa shows me several branches of his family tree. The desire to learn about his pedigree led to an excursion into the remote past. “We found people in his family who were born in 1705,” continues Ms. Liuta. “[Hetman] Ivan Mazepa was still living at the time. A death record dated 1756 let us calculate the birth dates for some other people. These people were called the Hetmanchuks in their village. But no one else in the village had this last name, so they must’ve been from the family of the hetman. But we’ll probably never learn who these people were. We can however say that Adam Mazepa, Stepan Mazepa, Vasyl Mazepa, Olekhno Mazepa, and others were there. They were all Volhynian noblemen, but we cannot put them into one genealogical tree.”

In 2008, Ihor and Mykola Mazepa set up an international NGO called “Rodyna Mazepa” (The Mazepa Family) in order to bring together the representatives of their historical family. “People with this last name are most often encountered in Volyn, Kyiv, and northern part of Chernihiv oblasts,” says Ihor. “This is where Isaak Mazepa, who was a prime minister in the UNR, came from. Journalist Anna Polikovska, whose maiden name is Mazepa, also comes from the Chernhiv branch. My calculations show that there are approximately 3,000 Mazepas living in Ukraine today, including around 1,200 are men and 1,800 women. This is 400 families. Another 500 to 1,000 Mazepas live in Brazil, Poland, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, in the city of Baturyn near Novosibirsk in Russia, etc. We are able to communicate via the Internet. There are over 230 Mazepas on Odnoklassniki and 50 on Facebook.”

The mission of the NGO is to improve the image of Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa and bring the truth about him to the attention of international community. “We’re trying to give all these family members an understanding of the fact that they are part of one and the same family and have been related in one way or another through centuries,” says Ihor. “For example, a remote relative of my father teaches at a Radyvyliv school and one of her students is Serhii Mazepa. She merely thought he had the same last name until she looked at the family tree and learned that he is her relative six times removed. The village of Borduliaky near Tesluhiv is one locale we studied. The former is in Galicia and the latter in Volhynia. They were divided by the border between the Russian Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so all Mazepas in Borduliaky are Greek Catholics, while the ones in Tesluhiv are all Orthodox. In fact, they are relatives who split into different branches several generations back.”

Everyone has opportunities to find interesting information about one’s family, but one must gather the courage to do it, because one never knows what he will find: a happy revelation or an unpleasant surprise or skeletons in the closet.

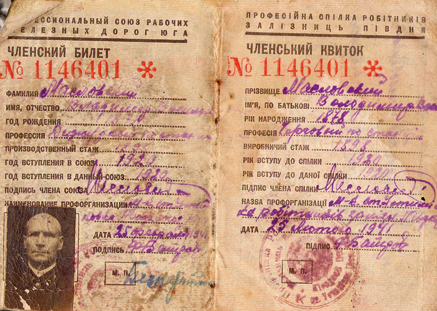

MEMBERSHIP CARD. Every document preserved in the family can be a source of unique information.

True stories

An employee at one Kharkiv archive told The Ukrainian Week about Holywood-style plots that can be found on the pages of archived documents:

“Our archive once received a letter from an attorney, a Swiss citizen, who was over 80 at the time. He was born in 1913 in Geneva into a Russian family, but in 1916 his mother, who was a Kharkiv native, returned to her motherland for some reason and disappeared. More than 80 years later he asked our archive about her fate. Our correspondence lasted for three or four years, and this is what we have found. A grandfather of this attorney hailed from the Valkiv district in Kharkiv gubernia. He was a serf, but 10 years after the abolition of serfdom he not only became rich but also took the mayor’s office in Valkiv. He later moved to Kharkiv and built a mansion in the city center. He fell in love with a girl, and as a result he had two children born out of wedlock in addition to three children born into the family. He adopted the former and made sure they obtained excellent educations. One of them was the mother of this Swiss attorney. She went to Switzerland for vacation and met a nobleman from Smolensk there. They got married in Geneva and had a daughter. But in late 1916, her father died and she went to Kharkiv to get her share of the inheritance. Then came 1917 and the revolution, and the connection with Switzerland was severed. Strange things were happening in Kharkiv at the time. A brother of the adopted sisters wrote a letter saying that both of them were mentally ill and both had similar symptoms. They were put in a psychiatric hospital which they never left. In 1941, they were shot by the Germans. And the man in Switzerland never learned where his wife had gone without a trace. Here you have the fate of one family complete with the abolition of serfdom, the industrial surge in the late 19th century, the revolution, 1941, and Hitler’s policy of killing the mentally ill.”

***

“A couple once came to me: the man wanted to learn whether his grandfather had been repressed, while his wife was interested in the life of her grandfather from the same village. I found out that the man’s grandfather was indeed repressed, while the lady’s grandfather was among those who testified against him. But I did not reveal this, because the man only requested to learn about his own grandfather.”

***

“As I processed documents, I came across the record of my grandmother’s testimony: she was a witness in a case against a repressed relative of mine. I have studied cases of repressed people many times, so I know for a fact how they broke down during interrogations. I knew my grandmother as a woman of high principles, but when I came across this case, I could not find the courage to read it. What if it turned out she had been finally broken, too? I didn’t want to read things like that about close relatives. I put the case away, but after a while I got back to it and read it anyway: I found my grandmother had behaved in such a dignified manner that I once again marveled at her.”

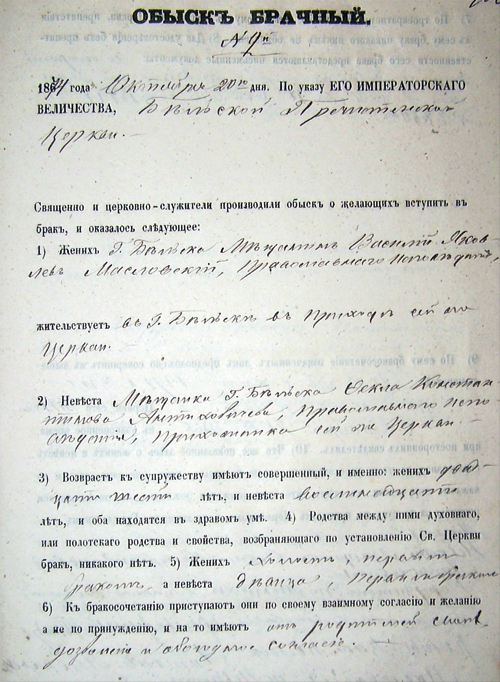

“Matrimonial examination.” Documents testifying that the bride and the bridegroom were not relatives are not common in archives, in particular due to the waste paper collection quotas set and dutifully met in Soviet times.

ANCESTORS. A photo taken in Fastiv in the 1920s.