LOOKING FOR ROOTS

The archives of the Chernivtsi Oblast have been overcrowded over the past few years. Thousands of Ukrainians are willing to pay significant amounts to find out about their genealogy. What they are actually look for is a document confirming that their ancestors, be it a grandfather, a great-grandfather or any other relative with a document written in Romanian, had once lived under the jurisdiction of Bucharest. Until 1940, the latter covered all of Bukovyna and part of the Odessa Oblast as the border between Ukraine and the Grand Romania went along the Danube. Now, all those whose relatives once lived under the “Romanians” are entitled to compensation in the form of becoming citizens of an EU state.

The happy owners of Romanian passports honestly admit that the red passports with golden eagles were only to help them avoid long lines at embassies. Plus, it was cheaper to pay for a passport once than for every visa.

According to independent experts, there are currently nearly 50,000 citizens with Romanian passports living in Ukraine. Anatoliy Kartashov, a professor at Chernivtsi University, is convinced that the government cannot sleep well as long as there are undetermined and actually illegitimate individuals with dual citizenship living on our territory. As an example, he cited the conflict from two years ago between Georgia and the Russian Federation when Moscow, while allegedly protecting the Russian citizens living in South Ossetia, started a war with sovereign Georgia. Is it possible that Romania could do the same some time in the future? “The Georgian-Russian conflict showed how a country can interpret the right to protect its citizens abroad in a brutal manner and dangerously broad the interpretation of the right to protect its citizens abroad can be, which can go as far as the initiation of military action”, Mr. Kartashov says.

The very likelihood of an armed conflict for the territory between Ukraine and Romania looks insane. But the General Staffs of the defense ministries of both countries take this possibility very seriously and have considered the possibility of war, at least in theory.

Meanwhile, Romanian officials claim that their state does not wish Ukraine ill. The fact that two years ago it simplified the procedure for getting Romanian citizenship for the citizens of some territories pertains more to Moldova and other countries that allow dual citizenship. However, for some reason, the website of the consulate and the Official Newsletter of Romania stopped publishing the lists of romanianised Ukrainians. Perhaps, this was because they became too many and they have all violated the law?

HOMELAND FOR SALE. CHEAP

Dozens of companies in Chernivtsi, Lutsk, Lviv, even Kyiv, can redraw your family tree for peanuts. They advertise online. Chernivtsi-based firms offer the cheapest services. I choose a random firm from an ad posted on a street light opposite the Romanian consulate.

I meet the dealers selling their homeland on neutral territory, in a park near the Bukovyna hotel. Two guys aged 30-35, describe the procedure for getting a Romanian passport. First, I need to find some Romanian ancestors. I admit I have none. “What about your grandparents?” the broker asks. “What are their last names?” “Zubenok, Lakhuba, Zyma, Boyaryn,” I say. “Never mind, we’ll arrange your Romanian roots,” the dealer comforts me.

We can apply for a passport in Chernivtsi, border town Suchava or Bucharest. “We will open a visa for you and you go to Bucharest with us,” the dealer says. “You will apply on your own. It’s all official.”

If Bucharest accepts the documents, this guarantees that I shall get Romanian citizenship. The change of native land costs EUR 2,000. Kyiv has higher rates – EUR 1.500 if you have genuine Romanian roots and if it needs to be bought – an additional EUR 5,000.

The Romanian consulate offers no comment on this homeland trading. They simply kick journalists out of their office. Before the door closes behind me, I ask about the line in front of the consulate. The clerk states that all these people are simply… hanging around.

ROMANIAMARE

As they buy another citizenship, Ukrainians don’t even think about why Romania needs this. For what purpose does a European country give out its passports left and right, while its EU neighbours are reluctant to grant a single-entry visa? Pavlo Kobevko, a Chernivtsi-based reporter, has been following the romanianisation of Bukovyna for several years now. He says that Ukraine could end up with yet another autonomous region in addition to Crimea if at least 20% of the region’s population holds Romanian passports. “At some point, part of the population with both Romanian and Ukrainian passports declare that they are the citizens of Romania,” he says. “and their leaders will say that there is a large enough Romanian community in Ukraine.” Mr. Kobevko is convinced that the Romanian government is still daydreaming of a Great Romania (see INFO) that includes Bukovyna and Bessarabia.

So far, Bukovyna has been romanianised quietly. 76 schools in Chernivtsi Oblast teach in the Romanian language and 13 more teach in both Romanian and Ukrainian. The total number of children educated in Romanian is almost 19,000. These are all state schools so they exist on Ukrainian taxpayers’ money. However, they teach students to love Romania, rather than Ukraine. For instance, in geography classes, students learn that Chernivtsi is a Romanian city and in history classes, that Bukovyna has always been part of Great Romania, so there was never any occupation of Ukrainian territory during WWII. By the way, students from these schools fail Ukrainian language tests on a regular basis, therefore are unable to enroll in Ukrainian higher education institutions.

But even this is not a problem. School graduates can get their degrees in Romania. Moreover, with the “blessing” of the oblast education administration, which arranges the exchange for future students. Professors from Romanian universities come to Chernivtsi every year to select applicants to their universities. Ukrainian professors, in turn, choose school graduates from Romania. After the interviews, almost 400 Ukrainian high school graduates move to Romania to complete their higher education, compared to less than ten Romanians coming to Ukraine. This is because Romania has virtually no schools teaching in Ukrainian, and the few that do, are privately-owned.

In addition to schools and higher education institutions, Bukovyna has Romanian-language newspapers and TV shows funded by the Romanian government. Still, those who campaign for the rights of Ukrainian Romanians, acting under the guise of cultural associations, are not happy – which is no surprise, as they are also funded from outside. Professor Kartashov recalls the early 90s when the interference was more palpable. “There were even incidents of open bribery and the encouragement of irredentism,” Prof. Kartashov says. “I can say this with certainty. The good thing is that Romania cannot afford such flagrant moves today.”

The biggest Romanian organization in the country is the Romanian Community in Ukraine, an interregional association, chaired by Ivan Popesku. Once a modest teacher and a post-graduate student of the Russian Language Department at Chernivtsi University, he was elected as a Peoples Deputy in 1994, a position he still holds, representing the Party of Regions. Mr. Popesku is also Deputy Chair of the Committee for Human Rights, Ethnic Minorities and Interethnic Relations. He is very well aware of the slow yet confident romanianisation of the Chernivtsi Oblast but does not consider it to be a problem, nor does he see dual citizenship as a big deal. In every interview, he mentions the European Convention on Nationality that interprets the notions of citizenship and nationality as being equal. Ukraine has ratified the Convention despite the fact that it runs counter to the Constitution. As a result, Mr. Popesku assumes that the Constitution will have to be amended very soon. This will happen, for example, once there are 1mn or more Ukrainians holding two passports. Moldova has already done this.

UKRAINE: NO ENTRY

An EU passport is a useful thing, of course, but it turns out that not everybody wants one.

Cheresh is a Ukrainian village, located 100 km from Chernivtsi. 90% of the locals are native Romanians. They have a Romanian school and all their signs are in Romanian. The villagers speak Romanian to each other. Yet, none of them own a red passport with a golden eagle.

Arkadiy Opoits is a Romanian poet and a Ukrainian citizen. He says that the old residents who spent their whole lives in the village do not need the citizenship of a neighbour country. The villagers respect the land on which they live. The poet talks with understanding about those who yielded to the temptation of the red certificate: “Romanians are a peaceful and balanced nation. They work and want a better life. When a country is unable to feed its citizens and give them the basic things in life, people start considering other options, other countries.”

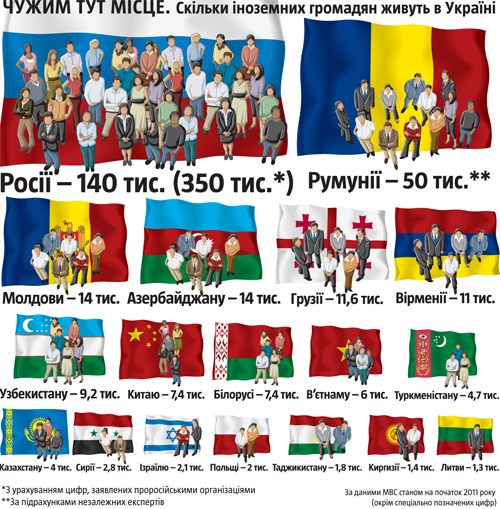

STRANGERS BELONG HERE. How many foreigners live in Ukraine?

Russians – 140,000 (350,000*)

Romanians – 50,000 **

Moldovans – 14,000

Azerbaijanians – 14,000

Georgians – 11,600

Armenians – 11,000

Uzbeks – 9,200

Chinese – 7,400

Belarussians – 7,400

Vietnamese – 6,000

Turkmens – 4,700

Kazakhs – 4,000

Syrians – 2,800

Israelis – 2,100

Poles – 2,000

Tadjiks – 1,800

People from Kirghizia – 1,400

Lithuanians – 1,300

*Including numbers provided by pro-Russian organizations

**According to independent experts

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs, as of the early 2011 (other than marked numbers)

Getting a Romanian passport is easy in Palanka, a village in Moldova that was once part of Great Romania. The local Moldovans also betray their homeland. Surprisingly, they do so in favor of Ukraine rather than Romania. Petro has relatives near Odesa in Ukraine, which is much closer to Palanka than Romania. He says that he would sell wine, potatoes and apples on the Odesa market if it were not for the border – or move to Ukraine, which would be even better. “I would love to move to Ukraine,” Petro says. “All my family lives in Ukraine. And I can’t bring them a sack of potatoes. Customs officers will take it away and make me pay UAH 2 per kilo. I can’t even bring in a bottle of wine – I’d have to pay for that, too.”

This brings the passport “brokers” in Chernivtsi to mind. As soon as I say that I can help him get a blue passport with a golden tryzub, the trident, everybody, young and old fall in front of me. I call the dealers but they express reluctance, once they realize that the issue at hand is Ukrainian passports. They say they can deal with Romanian, Hungarian, Polish and even Cypriot passports, but Ukrainian ones are not in demand, so no effective scams are available. “Tell them it’s easier to get ten Romanian passports rather than one Ukrainian passport,” the broker says. “They’d have to wait at least five years. In other words, it’s impossible.”

INFO

The concept behind the Great Romania (Rom. – Romаnia Mare) was to expand Romanian borders as much as possible during the period 1881–1947. In 1918, Romania annexed Transylvania, Bessarabia, Banat and Bukovyna. In 1940, during WWII, the USSR forced Romania to give away Bessarabia and North Bukovyna. In 1941, though, being Hitler’s ally, Romania got them back, moving its border farther east. This resulted in two provinces. One was Bessarabia that included the right-bank part of the Moldovan SSR and parts of the Odesa and Chernivtsi Oblasts, and Transnistria comprised of left-bank Moldova and parts of the Odesa, Mykolaiv and Vinnytsia Oblasts of Ukraine. Publications in the fascist Romania claimed that the territory beyond the Dniester river was inhabited by Romanians while the stretch between the Prut and the Southern Buh rivers should belonged to Romania. Some publications went as far as to say that the Great Romania should stretch all the way to the Dnipro.