Vladimir Putin and his Donetsk favorites have set up something similar to RosUkrEnergo on Ukraine’s grain market, giving Russia an in to one of the top five grain exporters in the world.

RosUkrGrain?

Last summer, there was lots of talk about some kind of grain market union between Ukraine and Russia, the idea apparently being that the world was in a food crisis so major players could cash in by dictating world grain prices cartel-style. But the talk proved to be just that. At any rate, no official word ever came of a Ukrainian-Russian grain conglomerate.

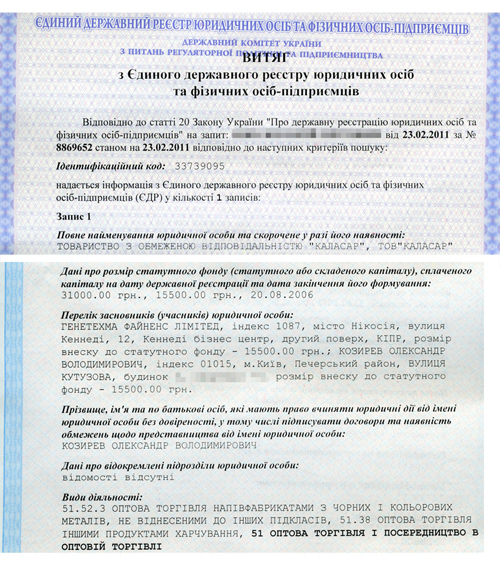

Unofficially is another matter altogether. In December, Ukrainskiy Tyzhden (#165) published its investigation into how the quasi state-owned grain investment company Khlib Investbud (KIB) had managed to monopolize the Ukrainian market. Although Agriculture Minister Mykola Prysiazhniuk has put it out that Khlib Ukrainy, the state grain company, had a 61% stake in KIB, official documents obtained by Ukrainskiy Tyzhden showed that the government had no longer controlled what has since become the country’s top grain trader since August 2010. De jure, the company is run by TOV Kalasar, a firm whose roots are linked to business circles around—Minister Prysiazhniuk. Ukrainskiy Tyzhden dug deeper and discovered that the threads lead even farther, to Russia.

The 50/50 owners of Kalasar are Oleksandr Kozyriev, who has connections to the Yenakievo business group, and Genetechma Finance Limited, a Cypriot offshore company. Normally, figuring out the owners of Cypriot firms is a tricky business, but these folks are not even trying to hide their traces. Cyprus-based Genetechma is a subsidiary of Luxemburg-based Bellevue Industries Sarl, in turn a subsidiary of VAT VEB-Leasing, a direct subsidiary of Russia’s foreign trade bank, Vnesheconombank (VEB) where Vladimir Putin is Chair of the Supervisory Board.

Meanwhile, KIB, a state-owned company according to Yenakievo-born Minister Prysiazhniuk, is in fact controlled by a private company in which both Yenakievo businessmen and Mr. Putin’s bank own equal shares. At RosUkrEnergo, Ukrainian oligarchs Dmytro Firtash and his partner Ivan Fursin also held 50%, while Gazprom had the other half. Obviously, everyone remembers what this entity, set up by Leonid Kuchma and Vladimir Putin and creatively expanded under President Yushchenko, led to: Gazprom ended up with 100% control over Ukraine’s gas reserves. Today, the Kremlin dictates both gas prices and volumes in Kyiv.

Weaving a fine VEB

To understand the situation better, let’s look at what Mr. Putin’s Vnesheconombank really is. Known also as the Russian Development Bank, VEB services the foreign debt Russia inherited from the USSR. Ten years ago, Mr. Putin chose this bank to support structural reforms in Russia as well. Today, it administers the pension savings of all Russians, giving it the richest financial base of all post-soviet countries. Four years ago, Mr. Putin set up the Bank for Development and Foreign Economic Affairs, a state-owned corporation, within Vnesheconombank. Since then, this bank has been Kremlin’s main agent in foreign markets.

Vnesheconombank has already shown its expansionist skills in Ukraine. The latest financial crisis started with the failure of Prominvestbank, the former soviet industrial investment bank and one of Ukraine’s biggest financial institutions. It was skillfully killed by a raider attack that spread panic among depositors. Vnesheconombank “saved” Prominvestbank by buying 94% of its shares—for peanuts.

Last year, Vnesheconombank serviced a transaction to sell Zaporizhstal, one of the biggest steelworks in Ukraine. VEB was also fingered in the disappearance of Vitaliy Haiduk and Serhiy Taruta from the round-up of Ukrainian tycoons. Just before the White&Blue Administration took over from the Orange one, pro-Tymoshenko businessmen were forced to hand over control of Industrial Union of Donbas to a group of Russian investors. This deal was also financed through VEB.

Mad money

Today, Mr. Putin’s bank is finding easy money on the grain market in Ukraine. Last summer, the state lost control over Khlib Investbud yet chose this company to be the state grain trader. KIB got a contract to buy 5mn t of grain in Ukraine worth UAH 7bn, an average of UAH 1,400/t. Later, the firm got a lion’s share of Government-issued grain export quotas. As a result, major grain traders like Nibulon, Kernel Trading and Serna, which had been working in Ukraine for years, were either pushed aside or kicked out of grain business altogether. Moreover, this monopolization of the grain market forced Ukrainian farmers to sell grain to KIB at the prices it dictated, i.e., cheap. Now, the state exporter is selling that same grain at higher prices—domestically. In other words, KIB’s practices on Ukraine’s domestic grain market are part of the reason why cheap flour disappeared from store shelves and bread prices have begun to rise (see p.26).

Meanwhile, businessmen have enjoyed the taste of victory so much that they are happy to dig deeper into the farmers’ stores. In February, the Farm Fund bought three lots of grain from KIB: 769,639,000 t, 895,214,000 t, and 1,030,280,000 t. The government needs to buy at least 2.7mn t to set up the national intervention fund in time. The Ministry of Economy gave the Farm Fund the go-ahead to pay UAH 1.55bn to KIB for just one of these contracts. This means that, regardless of which of the three lots of grain the contract is for, the price will be higher than the initial purchase price of UAH 1,400/t.

Obviously, whoever owns the pocket into which the profits from this deal will go is going to instruct those who administrate Ukraine’s grain market when, to whom and how much to sell the grain for. Russia has suspended its own exports of grain until mid-2011, based ostensibly on last year’s dry summer of 2010, they say. Ukraine followed suit and also virtually froze grain exports, although the 40mn-t harvest in 2010 was more than enough to feed both Ukraine and other parts of the world.

When two of the world’s top exporters suspended shipments of grain, wheat prices began to soar. Bringing grain to world markets at peak prices after buying it for peanuts at home promises windfall profits. It could even bring windfall political dividends, such as gaining control over some country that, for the sake of bread during a global food crisis, will be forced to “give in to peace,” as Mr. Putin likes to put it.