On 1 February 2012, President Viktor Yanukovych approved the 2012-20 Strategy for the State Personnel Policy establishing the New National Elite, a presidential reserve of staff. The new Elite is supposed to involve the most gifted Ukrainian citizens in implementing economic reforms and offer training to prepare them for work in priority domains of public administration.

FAVOURITISM AND INCOMPETENCY

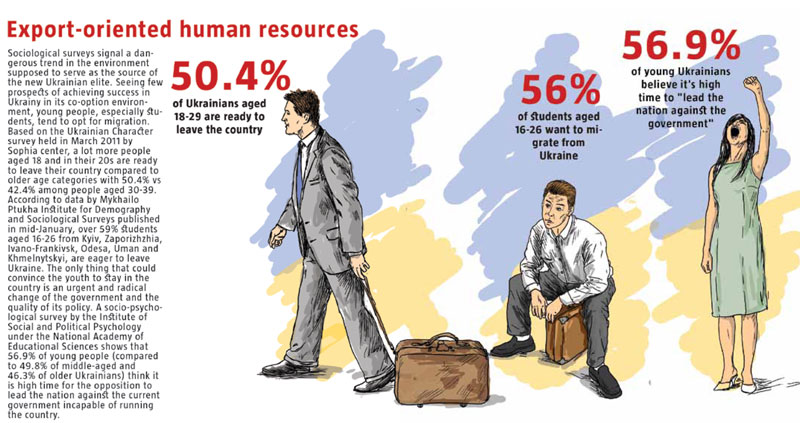

Ukrainians have for a long time been lamenting blocked “carreer ladders” in politics and public administration, i.e., channels through which every citizen can receive a real chance of entering the establishment based on knowledge and skills.

The structure of civil service in Ukraine (such as the members of the Cabinet of Ministers, top officials in the ministries, government services, agencies and regional state administrations), shows that just a handful (no more than 5-8%, according to our estimates) have achieved their status through objective evaluation of their skills and experience.

FOUR REASONS WHY

First, senior public servants who make up the public administration elite are appointed personally (and absolutely subjectively) by the president according to Ukrainian laws. Neither experience nor a diploma in a relevant field is required. Second, the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA), the institution that specializes in training government officials, does not have the reputation it should have as a body of this level. Third, as a result of business penetrating government structures, the main criteria for appointments to public office are membership in a certain business group, personal connections, lobbying by business clans, personal loyalty, etc.

Lastly, parties have quotas for top offices. For example, the Party of Regions’ parliamentary coalition partners – Volodymyr Lytvyn’s People’s Party and the Communist Party – had their members appointed to influential offices. Vasyl Volha, ex-chief of State Financial Regulator who is now under investigation, took his office as part of the Communists’ quota.

SOVIET LEGACY

The problem with forming public administration elites came with Ukraine’s regained independence, because the country took its first steps in the early 1990s led by the old elite which was a product of the soviet regime. Its representatives took all key public administration offices in independent Ukraine, from the president to his representatives in regions and districts. Additionally, so-called “red directors” (CEOs of large enterprises) – many of whom found national and state values, market mentality and democratic approaches in government policy making to be completely alien concepts – began to play an increasingly important role. Representatives of this new-old elite promoted nepotism. That burden remains with us today as we see children of high-ranking officials taking offices that offer prospects of rapid growth or access to the distribution of budget funds.

REVAMP OR ASSIMILATION?

Attempts were made in the first years of Ukraine's independence to establish ways to revamp the governing elite. On the local level, representatives of the People’s Movement of Ukraine (PMU) were promoted for positions in the government. In some regions, branches of the PMU succeeded in replacing deputy heads of regional administrations in charge of culture and education – but no regional governors or heads of financial administrations were replaced by them.

Elections to local self-governments were held in the early 1990s, and they – primarily regional councils and city councils in regional centers – became another “social lift.” Their executive communities were then part of the executive branch, so the elected heads of councils who also headed executive communities automatically became members of the new public administration elite. For example, Vyacheslav Chornovil was head of the Lviv Region Council and its executive committee; Vasyl Kuibida headed the Lviv City Council, and Vyacheslav Nehoda chaired the Ternopil City Council.

The Verkhovna Rada also played a part in changing the façade of the public administration elite in the 1990s. Representatives of the People’s Council opposition group obtained access to executive office. But this process had a limited impact. It was regulated and carefully guided, and the new appointees leaned more towards accepting the soviet rules of the game rather than bringing new standards to the establishment.

On the other hand, Ukrainian business entered the public administration elite through parliament itself. Ukraine began to gradually turn into an oligarchic economy as tycoons brought “red directors” under their control and business groups formed around key players. Representatives of these groups also ran for seats in parliament in order to protect their business interests. This was especially visible in the 1988-2002 convocation with such notable new arrivals as Inna Bohoslovska, Valeriy Khoroshkovsky and Vasyl Khmelnytsky.

Most representatives of this business elite shared the Moscow-centred worldview and came mostly from the country's eastern and southeastern regions, where the biggest industrial enterprises were concentrated and where their business, largely based on cooperation with oligarchs or “servicing” them, was developing. However, they also had a fairly pragmatic attitude to Ukraine's independence, viewing it as, among other things, a safeguard against takeover by more powerful Russian players. Still, they were oriented towards lobbying their own economic interests through the institutions of power in the “fastest possible” (that is, behind-the-scenes and corrupt) way.

The weakness of the personnel policy was evident since the early days of independence. For example, MPs of the first convocations had to create the legislation of a new state. As a result, many of them ended up having a high professional level. But dozens of other highly qualified specialists outside parliament were denied opportunities to apply their knowledge and experience in civil service.

Neither were gifted youth given many chances. Newcomers were eyed with suspicion by conservatively-minded officials. “Promising” offices were filled with their children and acquaintances. There was no special body that would implement a new cadre policy. Human resource management was and is still largely viewed in Ukraine as a technical process of filling empty slots in organizational charts or as a chance to put your own people in the best offices rather than as a way to carry out a policy aimed at enhancing the quality of public administration.

The first attempts to train senior civil servants came in the 1990s. But the Institute of Public Administration and Local Self-Government, which was originally set up by the Cabinet of Ministers and later renamed NAPA and attached to the President of Ukraine, never turned into a foundry of public administration talent for several reasons.

First, teaching methods were inadequate. Second, no distinctly higher status was conferred upon graduates of NAPA compared to those who matriculated at other colleges. Nor were they guaranteed job placement – there were a number of cases when NAPA graduates were unable to even return to their earlier places of work. Third, appointments of senior officials were placed, directly or indirectly, within the remit of the president without the need for any probation or trial period. Competitive procedures have been used exclusively with regard to administrative officers (categories 3-7), while appointments to higher offices are still made by the president or other government institutions.

OLIGARCHIC CLIENTELE

The circulation of the elites was greatly hindered during Leonid Kuchma’s second presidential term, when an oligarchic model for government decision-making was fully established in Ukraine. Since the late 1990s, most governments' decisions reflected a fine balancing act between several competing clans: Hryhoriy Surkis–Viktor Medvedchuk, Viktor Pinchuk and the Donetsk group. All of them lobbied the interests of large businesses and promoted their own people and their children for influential offices.

The declarations made by the Orange government about separating business and the government, which was supposed to stimulate an overhaul of the establishment, remained largely on paper only. One of the reasons is that large business was also very well represented on their team. (Think about Oleksandr Tretyakov, Petro Poroshenko, Yevhen Chernovenko, David Zhvania and other close associates of Viktor Yushchenko, as well as the oligarchs who “surrendered” to BYuT.)

The leaders of the Maidan essentially turned out to be made of the same soviet material as their opponents. In 2005, over 19,000 government officials (a little less than 10% of the total, which is around 270,000) were fired. However, in many cases they were replaced by civil servants who were no better but simply loyal to the new powers-that-be.

The new government declared its intent to attract young people who had diplomas from Western universities, but this plan failed, too. First, concrete mechanisms were never found for enabling the policy and second, the issue of motivation remained unresolved (a Harvard graduate was unlikely to agree to a monthly salary of $500-$1,000).

The main thing was that no one was committed to finding solutions to all these problems which were known long in advance. Consequently, those who entered civil service on the wave of the Orange Revolution with a desire to change the situation found themselves in the minority, while their initiatives were buried under the pretext that they were “currently irrelevant” or “needed further elaboration.”

ANOTHER IMITATION

The current leadership of the country is turning reforms into advertising campaigns. The public administration reform, in particular “creating a new elite”, is no exception. But the idea to set up a presidential cadre reserve seems to be especially strange.

Why is it “presidential”? If it refers to the president’s appointees and their offices, such a reserve already exists. Moreover, a special procedure for its formation was established five years ago by Cabinet of Ministers regulation No. 272 dated February 21, 2007. It pertains to category I-III civil servants who are appointed or whose nomination is approved by the president and the government.

If, however, it refers to a reserve for all public officials (which does not make much sense, because the president does not appoint most of them), this reserve has been formed by now. Furthermore, these two reserves have proved to be critically inefficient in practice.

The content of the New National Elite idea does not stand up to criticism, either. A pilot project carried out by the Presidential Administration shows that this reserve will in no way change the way the “reformist” cadre are trained and selected.

According to public information from the Presidential Administration, the program includes three stages: 1) Training Leaders in the Public Sector (an eight-day course); 2) workshops on working in the public sector (8-10 days); and 3) employment in the public sector. If this is the president’s “new elite,” it is too bad for the nation. It would be ridiculous to assume that a civil servant, to say nothing about a top official, can be trained in three weeks.

Therefore, when looking at the president’s strategy, one must wonder: What is the point of setting up another cadre reserve instead of improving existing ones? Notably, on 10 January 2012, Yanukovych signed a new law on civil service which eliminated cadre reserve in government bodies starting from 1 January 2013.

WHAT TO DO NEXT?

There is no need to reinvent the wheel. We can and should use the best world practices in training civil servants. And we have to completely change our approaches to the cadre policy in order to produce specialists that will be able to implement reforms and modernize the public administration sector.

Initially, we ought to introduce transparent procedures for filling senior administrative offices and set requirements regarding the education and experience of administrative work that successful candidates must possess.

The next step would be to reform NAPA, which is currently issuing diplomas indiscriminately and producing mediocre specialists. But instead of turning it into a large training center, as some are suggesting, we need to adopt the experience of European, Canadian and other schools in training civil servants.

For example, the École Nationale d'Administration is one of the world leaders in training senior officials. A two-year course includes, apart from studies, nearly four months of internship. Its graduates have a comprehensive view of civil service and are able to participate in the most difficult decision-making processes. Germany’s Higher School for Public and Municipal Administration and the Canada School of Public Service combine theoretical knowledge with several-month internships.

Of course, the idea of having a cadre reserve should not be discarded. But it should include transparent selection (testing) and a system for upgrading the professional level of the “reservists”: staff rotation, further training, self-education and so on.

At the same time, agreements should be signed with government bodies in foreign countries to give Ukrainians training opportunities in which they will acquire practical experience in specific offices rather than attend a several-day lecture course or workshop.

Ukrainefaces the urgent issue of strategic planning with regard to the government cadre policy. There is a need for a new public administration elite that will know where national interests lie and assume responsibility for their realization. This elite will have to be prepared to not only make tough decisions but also efficiently provide public administration services.

People who pursue such ambitious goals like overhauling the national public administration elite must believe in what they are doing rather than merely create the illusion that they are implementing real changes. Ukrainians do not need documents for documents’ sake or strategies for strategies’ sake. They need results. So when the government makes public statements about the presidential cadre reserve, it must know that it has nothing in common with public relations. It is not an image-boosting project, because it cannot have short-term results. There are doubts, however, that Bankova Str. is aware of that fact.