Local elections are always more inflexible and chaotic than the most heated national campaign. The reason is the sheer number of interested players – around 271,000 candidates were registered in this year’s campaign – while informational white noise distracts people, often leaving them with skewed impressions. TV presenters keep repeating the mantra about «the dirtiest»and «the most dishonest»campaigns, typically comparing apples and oranges and promoting the notion among Ukrainian voters that democratic institutions are on the decline.

In reality, things were far more interesting, even intriguing. According to a survey by the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DIF), 16.2% of voters were convinced that the local election would be fair and without fraud, 41% expected occasional violations that would not affect the result, 23.2% assumed that the result could be distorted, 6% were convinced there would be electoral fraud, and 13.6% had no opinion. In 2010, just 8.5% thought that the election would be fair and without fraud, showing that trust in elections and their democratic nature has grown significantly among Ukrainians over the past decade.

Every election campaign is like a new child with its unique character, charm and the context into which it is born, takes its first steps and grows. The 2020 local election was unique, as it completed the cycle of decentralization reforms, pushing political and local elite to directly engage in the process, and requiring a lot of resources, including media, to promote the top candidates and moving the local election system to one based on parties. The race was not for the secondary grassroots layer of administration, as it was seen in the past, but for the proper horizontal system of government with extensive powers and real resources.

In terms of election costs, Ukraine is far behind western countries, such as the US, where the right of candidates to collect donations for their campaign chests is equal to their right to freedom of speech. If election funds or the conditions for legal, transparent accumulation of campaign funds are restricted, candidates will not have the resources to promote themselves and engage with voters. Their right to freedom of speech will be impinged upon, as will voters’ right to access to information. Ukraine still has a long way to go to transparency and effective checks against political corruption: any investor wants a profit and the more that is invested, the higher the expectations of a return.

RELATED ARTICLE: The most important mayors

So far, neither the government nor NGOs have been able to determine the ratio of legal and shadow funding in election campaigns in Ukraine, but it’s no more than 40% legal to 60% shadow. Anything that can be covered by the term «staffing» is not accounted for, because commission members, promoters and even professional staff at campaign headquarters, and party election observers all work unofficially. Over UAH 2.1bn was allocated for local elections from the state budget, UAH 1.4bn of which was supposed to be spent on the token UAH 400 being paid to commission members. This makes additional zeroes and shadow funding budgets hard to calculate.

The typically unusual problems of this campaign included a change in legal regulations and the election system itself shortly before the election. While most political observers will declare that this has always been the case, Ukraine has never seen such tectonic changes less than a month and a half before the official start of a campaign. The new Election Code, which was applied for the first time in a real campaign last fall, needs to be seriously amended after every election cycle. It takes two or three campaigns to properly refine the Code and make it generally acceptable. The Central Election Commission (CEC) took on responsibility for interpreting certain rules and procedures, which might have had a fatal impact on the campaign. This approach can be used once during a transition period, but not regularly.

Meanwhile, the key political factor of this campaign was the structuring of the election along party lines and the nomination of candidates in most unified territorial communities (UTCs) and all councils from parties that represented their interests. The parties that effectively did not exist on the ground in villages, towns and even smaller cities ended up with a major and unfair advantage. Yet the obsession with political brands did not always have a direct effect in local elections. For instance, in 2019, the situation was straightforward: Volodymyr Zelensky gained record-breaking support among voters, built a party that served as a banner for candidates for the Verkhovna Rada, and replicated the results of the presidential election in the Rada vote, thanks to a combination of factors. In 2020, every relatively strong local leaders, politicians and mayors were forced to join parties represented in the Rada or with a nationwide rating – or else create their own «franchise» party.

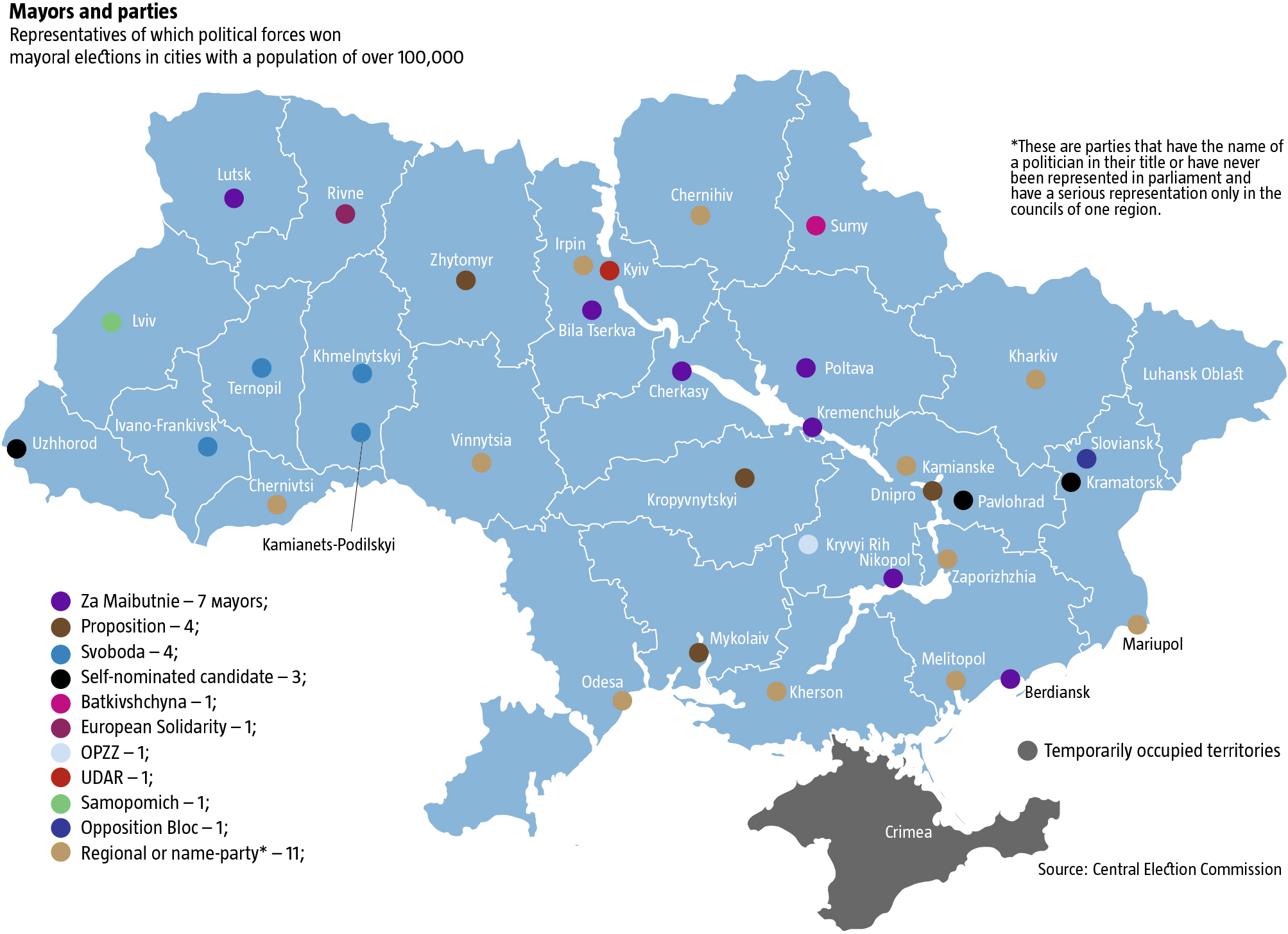

The last option proved the best one for candidates who were reluctant to deal with party ratings, negative ratings or future commitments barely a month before the vote. It was easier to sell the voters a well-known name or good administrator who had shown results, in the context of decentralization, during their previous term in office. As a result, mayors only changed in the cities where incumbents did not run, such as Rivne or Kryvyi Rih, where Kostiantyn Pavlov, Yuriy Vilkul’s successor, won. In fact, Pavlov was already openly acting as an advisor to Vilkul between the first and second rounds, chairing public events, calling official meetings, and so on.

But the election results seen in the light of major cities were deceptive, as were projections for UTCs based on national party ratings. In fact, the «party of self-nominated candidates» came out the winner of this election with 15.61%, thanks to UTCs with populations under 10,000, where self-nomination was effectively allowed. Sluha Narodu[Servant of the People] came second with 15.04%, followed by Batkivshchyna [Motherland] with 10.49%, Opposition Platform-Za Zhyttia [For Life] (OPZZ) with 9.89%, Za Maibutnie [For Future] with 9.58%, and European Solidarity with 9.18%. Local parties with small national ratings ended up with 30.21% of all seats.

RELATED ARTICLE: Dinosaurs vs «Dinosaurs»

The OPORA network estimates that, of the more than 21,000 candidates elected under the proportional system as of November 20, 2020, 59.9% gained seats in oblast and county councils and the councils of UTCwith a population of over 10,000 as party-list candidates in single multi-seat constituencies, while only 40.1% did so in territorial constituencies where the voters actually vote. Unfortunately, this means that the electoral system is not open enough: candidates cannot move up a party list unless they personally pick up 25% of the votes needed for a full mandate. As a result, those running for oblast councils in territorial constituencies had the best chance of being elected, 53.8%, compared to just 36.9% for those running forUTC councils. In other words, the more voters in a constituency, the better the chance of being elected there. 64.1% of OPZZ nominees made the 25% quota, followed by 53.7% nominees from European Solidarity, 53.2% from Sluha Narodu, and 50.9% from Nash Krai [Our Land]. If candidates had to gain just 5%, rather than 25% of the vote to move up the party list, the election system would be 91% open. In fact, the previous version of the Election Code had this very rule – and it should be returned if Ukraine’s lawmakers want to democratize the electoral process, and give voters more power over election results and over consistent work on developing internal party democracy.

The greatest challenge for the newly elected councils is to make sure that the majority engages in quality, effective work, that there’s a proper balance between national and local party interests, and that the powers of, say, county councils, is clearly delineated in legislation.

America’s Founding Fathers and the authors of its Constitution foresaw some developments that are still significant for many today. Among others, John Adams said about parties which represent part of the community, not the entire community, so competition among them will lead to the division of the nation.

The key question for Ukrainian parties is whether they will act on the basis of the same principles as 300 years ago or follow modern trends, and, if so – which ones? Affected by populism and super-effective, unrestricted direct communication with voters, party systems are dwindling even in democratic countries. The liberal way of regulating party activity is moving towards stricter self-regulation. Parties in Ukraine today mostly have flexible ideologies that shift from time to time, whereas party narratives risk aggravating social divisions where this can be avoided if some share of local councils were elected from lists of independent candidates. If elections are to take place under the party system in the future, reforming election legislation needs to start with the reform of party structures and related legislation. Rather than expecting the government to regulate party work, which would be undemocratic, these changes should foster conditions that will give party members influence over how party organizations operate, and make them more open and accountable to voters.

Olha Aivazovska, Board Chairman of Civil Network OPORA and Global Network of Domestic Election Monitors (GNDEM)

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook