The last five years have seen Ukrainian-Russian trade relations actively decline. The original impulse came when the Customs Union was set up in 2011 by Russia with Kazakhstan and Belarus, following which Russia began trade wars against Ukrainian manufacturers and producers as a way to force Ukraine to also join. In summer of 2013, pressure grew once more as President Viktor Yanukovych prepared, for all intents and purposes, to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union that included a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement. With Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine in early and mid-2014 and the economic component of the AA between Ukraine and the EU coming into force in 2016, the process accelerated steadily.

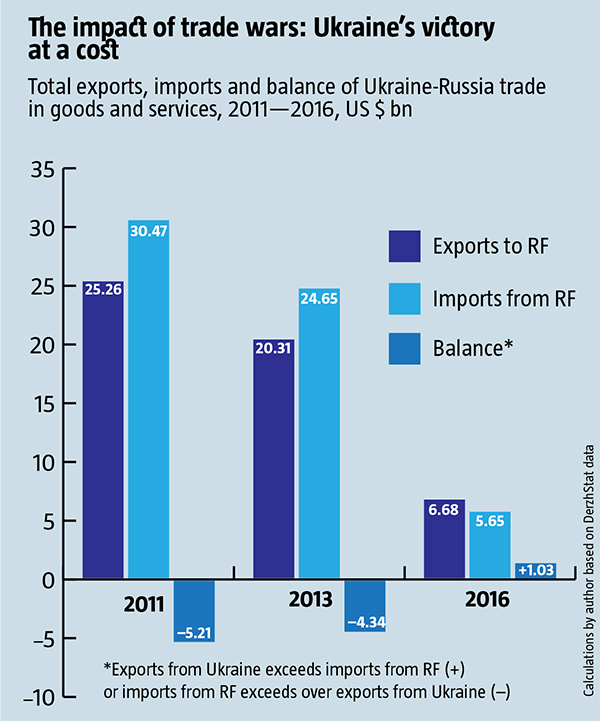

The economic aspect of Russia’s hybrid war has cost both countries enormously. By 2016, Ukraine’s exports of goods and services to Russia had shrunk to US $6.68 billion from US  $20.31bn in 2013 and US $25.26bn in 2011. Russian suppliers lost even more: imports from Russia collapsed to US $5.65bn from $24.65bn in 2013 and US $30.47bn in 2011. The winner, if one can even talk in such terms in this kind of situation, turned out to be Ukraine. Its huge trade deficit with Russia, which amounted to US $5.2bn in 2011, had turned to a surplus of more than US $1bn by 2016.

$20.31bn in 2013 and US $25.26bn in 2011. Russian suppliers lost even more: imports from Russia collapsed to US $5.65bn from $24.65bn in 2013 and US $30.47bn in 2011. The winner, if one can even talk in such terms in this kind of situation, turned out to be Ukraine. Its huge trade deficit with Russia, which amounted to US $5.2bn in 2011, had turned to a surplus of more than US $1bn by 2016.

A sloppy clean-up

The main thing is that Russia lost its status as Ukraine’s key trading and commercial partner, a dependence on its larger neighbor that forced the country, for more than two decades, to concede to Moscow’s demands, even when Kyiv enjoyed a pro-European administration, and made the majority of its producers effectively Russian lobbyists. This release from its dependence is now a fact at the level of the economy in general, but has not yet been absorbed in the consciousness of Ukrainian business—which can be seen in the way a large chunk of it positions itself. The consequence is that too many businesses have remained pro-Russian through sheer inertia.

This is partly encouraged by the remnants of economic dependence on Russia, as well, by the large debts that a slew of Ukrainian companies have at Russian banks. Other factors include the dominance of imported Russian top managers, the continuing and significant dependence of strategic domestic sectors on supplies of raw materials and fuels from the RF, and the dependence of certain export goods on the Russian market. To overcome these factors, a new push is needed, either from ordinary Ukrainians or from targeted restrictive measures on the part of the state—perhaps both.

The biggest positive impact in releasing Ukraine from the dominance of Russian business more recently can be attributed to the sharp loss of position by IUD, the Industrial Union of Donbas, a corporation once owned by Serhiy Taruta and now controlled by Russia’s Vneshekonombank. In 2013, it was responsible for almost 20% of Ukraine's metal output; since the blockade of ORDiLO, it has almost completely lost its market. Another factor was the sale of the Kharkiv Tractor Plant by its Russian owner. Yet another one is sanctions against Russian banks and other companies, which is forcing them to find a way out of the Ukrainian market, including the sale of the Ukrainian subsidiary of Sberbank, the Russian state savings bank.

RELATED ARTICLE: The first lessons of decentralisation in Ukraine

Still, there remains the threat that these sales are fictions, because the buyers are Russian business entities, the way it was with Sberbank in Ukraine. Or that someone is taking advantage of the situation to reduce the evident presence of Russian business on individual Ukrainian markets in order for them to be dominated by companies that are nominally Ukrainian, but are actually owned by Ukrainian compradors who are closely linked to Russia, such as SCM’s Rinat Akhmetov or Oleksandr Yaroslavskiy, who has long been an agent for Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska.

In a discussion of the prospects and purpose of maintaining Russian business in Ukraine that took place in March 2016, the President of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RUIE) Aleksandr Shokhin told those present that, according to Putin, “you have to be patient a little longer. At least there’s still a chance.” As long as this opinion does not change to its opposite and we don’t see a large-scale, irreversible exit of Russian businesses from Ukraine, there’s a great deal that needs to be done.

It is also evident that an opposite tendency is taking place: a growing presence of other Russian FIGs on the Ukrainian market, such as the Alfa Group, which recently added Italy’s UniCredit—and along with it, its subsidiary and one of Ukraine’s larger financial institutions, UkrSotsBank—to a portfolio that already contains its own eponymous Ukrainian subsidiary. Alfa also continues to control the largest mobile operators in Ukraine, Kyivstar, and has a stake in a smaller one, life:), and the other major operator is owned by Russia’s Mobile TeleSystems, which has rebranded its Ukrainian subsidiary as Vodaphone. Dozens of other Russian providers also continue to operate on the internet and telecoms service markets.

In this regard, the recent decision to add owners of Russian social networks to Ukraine’s sanctions list seems like just a small step in a huge task that needs to be undertaken to free the country from the domination of Kremlin agents in strategic sectors. Because any Russian entity operating in these sectors is completely dependent politically on Russia’s security forces for its survival.

Trends in bilateral trade in services

Exports of Ukrainian goods to the Russian Federation bottomed out in 2016, possibly temporarily, at US $3.59bn or 9.9% of Ukraine’s overall exports compared to US $15.05bn or 23.8% in 2013, and US $19.8bn or 29.0% in 2011. Since the beginning of 2017, exports began to rise again, reaching US $1.28bn over January-April, which is 38.5% more than for the same period last year. Still, the trade wars of recent year have led to a situation where the cumulative domestic export to Russia, the volumes of goods and services are almost equal. Nearly US $3.09bn of services or 32.1% of overall exports of services from Ukraine went to Russia in 2016. The decline in such exports compared to 2013 and 2011 is also significant, when they were 36.9% and 38.5%, but nothing compared to the collapse of trade in goods.

At first glance, Ukraine’s dependence on the export of services to Russia remains considerable, and exchanging them seems beneficial primarily to Ukraine, as it ensures a substantial surplus balance of US $3.1bn, compared to less than US $0.5bn of imported services in 2016. However, these apparent figures hide a radically different reality. The lion’s share of domestic exports is transport services, which constituted US $2.77bn or 89.6% of all exports and US $2.63 of the trade surplus. But included in these figures is more than 80% of the cost of Russian gas that transits through Ukraine’s gas transport system (GTS).

This transit is a service exported to Russia only as a consequence of the fact that, at one point, Ukraine’s leadership allowed the Russians to maintain their colonial approach to Ukraine and its GTS. And so gas is sold to Europe, not at the Ukrainian-Russian border, as it should be, but on the Ukrainian section of the one-time border of the USSR. In the end, this approach entrenched Ukraine’s status as almost little more than a Russian autonomy, a territory through which Gazprom simply transported its fuel to consumers. Once Ukraine puts into effect its announced intention to change things when the current contract with Gazprom expires in 2019, European consumers will be buying Gazprom’s natural gas at the border between Ukraine and Russia, and the transit services will then be exported to EU countries, not to the Russian Federation.

RELATED ARTICLE: What's missing for the management of state enterprises to be properly reformed?

If transporting gas is removed from the equation, it turns out that there is no other serious component in the export of services to Russia from Ukraine. And that means that Ukraine has a significant positive balance only in such service areas as IT, with US $145.1 million exported vs US $68.1mn imported, equipment maintenance and repair with US $29.3mn vs US $5.3mn, construction with US $5.5mn vs $1.3mn, and processing raw materials on a tolling basis, with US $4.2mn vs US $0.9mn. Russia, by contrast, has a huge positive balance in providing a slew of services to Ukraine, suggesting that the post-colonial inertia in business, finance and insurance remains: business services with $206.7mn imported vs US $119.1mn exported, financial with US $34.6mn vs US $2.7mn, insurance with US $5.7mn vs US $1.0mn, as well as royalties and other matters related to intellectual property with US $10.5mn vs US $7.2mn.

Weak spots in bilateral trade in goods

The weak spot for Ukraine’s export goods to the RF remains the fact that most of them continue to constitute a major share of their makers’ overall exports. For instance, over January-April 2017, 70% of all Ukrainian deliveries to Russia represented 40%+ of the total export of such goods out of Ukraine, while for around 30% of deliveries to the Federation, the Russian market represented 70%+ of the total export of such goods out of Ukraine. To be more precise, nearly all of Ukraine’s alumina exports—96.1% worth US $166.6mn in Q1 of 2017—and all of its exports of radioactive elements and isotopes, worth US $36.6mn, end up on the Russian market. They are the final remnants of Moscow’s strategy of incorporating Ukrainian assets into the “transnational corporation” known as the Russian Federation.

In the case of alumina, it’s about the output of the Mykolayiv Alumina Plant (MHZ), which is part of Deripaska and Partners’ Rossiyskiy Aluminia [Russian Aluminum]. Indeed, the domination of the Russian monopolist has led to a situation where, despite its capacity to satisfy all of Ukraine’s domestic needs and even export aluminum and goods made of it, Ukraine still imports it to this day, including from Russia! Meanwhile, the commitments Rossiyskiy Aluminia made to build an aluminum plant in Ukraine and process part of the alumina into aluminum locally during the privatization of MAP were forgotten the moment the papers were signed. Moreover, for a long time, RA deliberately blocked the work and effectively destroyed another enterprise in the industry, the Zaporizhzhia Aluminum Plant (ZAK).

The export of all of Ukraine’s nuclear materials to Russia, which is reprocessed into nuclear fuel and other materials in the Federation and then imported to Ukraine as a finished product, is similarly the consequence of many years of failure on the part of Ukraine’s governments in establishing a domestic nuclear production cycle for the country’s atomic energy stations (AESs).

The export of all of Ukraine’s nuclear materials to Russia, which is reprocessed into nuclear fuel and other materials in the Federation and then imported to Ukraine as a finished product, is similarly the consequence of many years of failure on the part of Ukraine’s governments in establishing a domestic nuclear production cycle for the country’s atomic energy stations (AESs).

Still, substantial dependence, more than 40% of all exports, on the Russian market can be seen in an additional 30 or so other Ukrainian commodities whose deliveries to the RF are worth nearly US $1bn a year and more—each. These are predominantly a large variety of machine-building products, which were connected to supplying components to Russian enterprises: turbines worth US $83.1mn over January-April 2017, or 66.8% of all such exports from Ukraine; railcars worth US $22.5mn or 82.4% and locomotive railcar components worth US $24.5mn or about 53.0%; liquid pumps worth US $24.2mn or 65.9%; electric motors and generators worth US $16.1mn or 63.5%; transformers worth US $12.3mn or 44.7%; motion transmission mechanisms worth US $14.5mn or 68.5%; farming equipment worth US $11.5mn or 64.8%; and equipment for moving soil, rock and ores worth US $8.9mn or 62.5%.

For these manufacturers, it’s clear that the Russian market remains key to their export business and sometimes even represents most of their production, however small the orders might be. On one hand, this illustrate just how flaccid are the marketing and production strategies of the management of these enterprises, which are not putting serious effort into finding opportunities to reorient their production facilities towards modified versions of items that could be sold to different markets or even domestically. On the other, it also shows that the government is doing little or nothing to encourage this kind of reorientation from the Russian market to the domestic one or other foreign ones. For instance, it could offer targeted interest-free or low-interest loans for the purchase and modernization of equipment and for retraining personnel. There are also not enough public procurements and often unjustified preferences in purchasing that kind of equipment and technology in Ukraine itself.

A huge dependence on the Russian market is also evident among certain types of finished rolled steel products. For instance, 77.5% of all of Ukraine’s exports of steel angles, structural bars and sections, worth US $72.3mn in the first four months of 2017, 58.1% of all galvanized flat-rolled steel, worth US $27.8mn, 72.7% of stainless flat-rolled steel, worth $20.0mn, and 48.1% of bars, rods and sections of corrosion-resistant steel, worth US $14.5mn, are exported to the Russian Federation.

RELATED ARTICLE: How coal trade with the occupied territory of Ukraine benefits Rinat Akhmetov

Clearly, the export of certain types of steel to the RF was huge within its category, even though it was relatively minor compared to the total export of all steel products from Ukraine, worth US $1.4 billion during this same period—never mind all ferrous exports, which were worth US $2.9bn. Ukrainian pipe-makers have pretty solidly moved away from the Russian market, after being the focus many a trade war between the two countries in years past: over January-April, they shipped only 24.3% of their products, worth US $31.2mn, to the RF.

Other industrial manufacturers, however, still are quite dependent on this market. 50.5% of Ukraine’s wallpaper products, worth US $20.2 million over January-April 2017, went to Russia, 58.4% of ceramic tiles, worth $12.8mn, 45.1% of uncoated paper and cardboard, worth US $9.5mn, and 50.0% of plastic containers for transporting and packaging goods, worth $13.5mn. Even though this represents sectors that are far from leading ones in Ukraine’s economy, each of their annual sales to the Russian market amount to generally UAH 1bn and more and their share of overall exports is quite large. So the loss of the Russian market for many manufacturers in key sector could be quite painful.

And so, the shrinkage of the Russian market share from around 30.0% to only 9.3% of exported domestic products in the first four months of 2017 does not reflect the uneven share of individual groups of goods. The fact is that the majority of industries either export only a few percentage points of their product or none at all to Russia. The basis for Ukrainian deliveries to the RF continue to be predominantly those products that are simply very dependent on this particular market and makes these manufacturers very vulnerable not only to the economic situation in Russia but to bilateral relations. In terms of Ukraine today, this means that they will inevitably tend to lobby Russian positions.

Threats to economic security

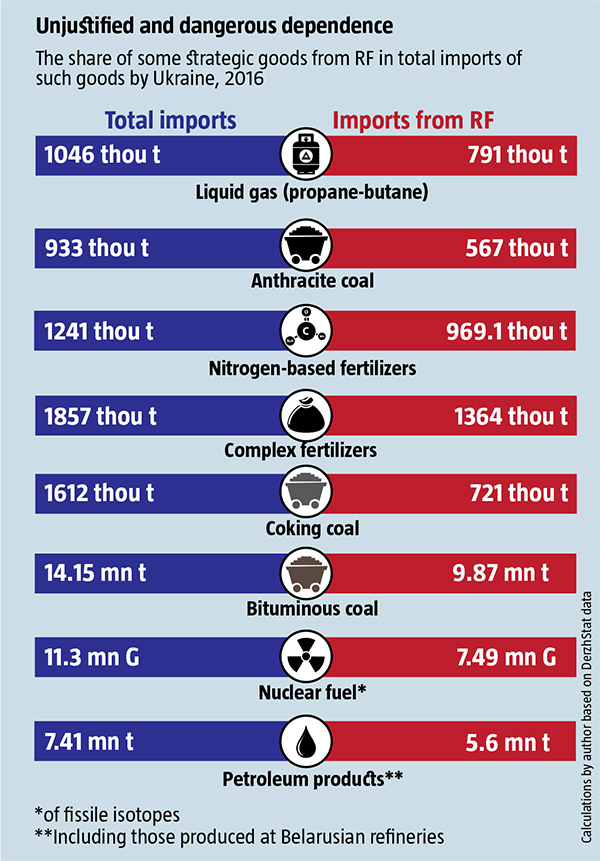

Meanwhile, Ukraine is enormously dependent on imports of most of its raw materials and fuels from Russia, which constitutes a threat to the country’s economic security in key sectors: the power industry, steel-making and farming. Moscow has demonstrated on many occasions its readiness to use not only restrictions on imports of Ukrainian goods that are very dependent on the Russian market in its hybrid war against Ukraine, but also restrictions on the delivery of raw materials and fuels from its own suppliers. Such artificial shortages threaten to cause serious problems for Ukraine’s economy. The latest examples are coal, piping and liquid gas. Moreover, this does not mean that in the future this kind of manipulation might not be extended to other commodities for which Ukraine is critically dependent on supplies from the RF. Most of these can obviously be substituted by switching to other suppliers, but with Russia delivering 50-80% of the needed quantities today, switching in a hurry is likely to present real problems. That means that this switch needs to be happening gradually, already today.

In the power industry, this means the hyperdependence on Russian nuclear fuel at Ukraine’s AESs, and on Russian anthracite, petroleum products and liquid gas at its cogeneration plants or TESs. The example of nuclear fuel is one of the top success stories in this regard. Although 66.3% of Ukraine’s nuclear fuel for its AESs, calculated in fissile isotopes, and 70.5% in terms of value was imported from the RF in 2016, this was still considerably less than just a year earlier, when the same shares were 90% and 95%, while in the first four months of 2017, the share of RF imports of fuel assemblies was down to 53% by value.

With other forms of energy, the situation is much worse. In 2016, 69.8% of all anthracite imports were from Russia, 66.7% by value. Since the beginning of 2017, all deliveries came from Russia, despite earlier announcements by the Ministry of Power and Coal that they would be banned. Moreover, there are indications that shipments of anthracite to Tsentrenergo, one of the central power utilities, marked as apparently coming from Georgia appear to have been fictitious sales.

The situation is also critical with deliveries of petroleum products and liquid gas. Fully 75.6% or 71.7% by value of the former came to Ukraine from the RF and Belarus in 2016, even though in 2015 only 67.9% and 66.7% did. This year, the share is up to 77.0%. In 2016, 75.6% of all liquid propane-butane came from the RF or 75.4% by value, while another 20.7%, 19.1% by value, came from Belarus. By comparison, these same imports in 2015 amounted to only 60.4% and 58.3% from Russia and 93.1%, 89.9% by value, for the two countries combined. And so we can see, not only complete dependence on supplies from the only realistic source, and continuing pressure to reduce supplies from alternative sources. Yet it would seem that the import of this kind of gas should be a lot simpler to diversify than imports of piping.

RELATED ARTICLE: The social and economic distortions of the tax-paying system in Ukraine and ways to change that

In the metallurgical industry, Ukraine is hyperdependent on deliveries of coke and bituminous coal from Russia, which is needed to process ores. The share of RF imports of bituminous coal grew to 69.8% in 2016, or 63.2% by value, compared to 55.0% and 46.8% in 2015, while imports of coke rose to 44.7%, 45.1% by value, compared to 34.5% and 36.9% in 2015—although the total volume of imported coke in 2016 was actually down from 2015.

In the farm sector, dangerous dependence levels can be seen in imports of Russian nitrogen-based and especially complex fertilizers. In 2016, 78.1% of nitrogen-based fertilizers, 80.6% by value, came from the RF. The lion’s share of other fertilizers came from Belarus, whose enterprises are completely dependent on the supply of gas from Russia, which is needed to produce them. Ukraine also gets all of its semi-finished ammonia to produce fertilizers at domestic plants. Lat year, 73.4% or 67.4% by value of all complex chemical fertilizers came from the RF as well, representing a domestic market share that is significantly larger because of the smaller output volumes from domestic manufacturers.

And so, overcoming Ukraine’s critical dependence on Russian imports of raw materials and goods that are important for the economic security of the country requires active, immediate measures to gradually diversify supplies. At the same time, it’s important to avoid getting into prohibitive tariffs and other mechanisms that simply provide artificial breaks to individual market monopolists and create problems for consumers, as happened not long ago with mineral fertilizers.

A more measured and long-term instrument against dumping and monopolization on the Ukrainian market by Russian suppliers could be to apply a cap on the volume of deliveries from a single source, say, not more than 25% or 35%, which is acceptable according to domestic anti-monopoly legislation. But the calculus for such measures must be based on the real, not nominal, country of origin of each product. For instance, it’s obvious that supplies of petroleum products or liquid gas from Belarus should be treated as the equivalent of supplies coming from Russia, which is the sole source of all raw materials for producers in Belarus.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook