As Karl Popper was writing his Open Society and Its Enemies, one of the ideological cornerstones of contemporary European liberalism, threats to civil society were expected to come from a variety of different sources. Standing in the way of a community of free citizens capable of joining forces and defending their rights were government agencies (they sought to justify their own existence, expand their staff, increase expenses and thus make more room for corruption), passive citizens (with their distinctively uncritical treatment of the government), paternalism and traditions that have formed in certain societies.

All of this holds true for Ukraine. But equally harmful to our emerging civil society are imitators and timeservers who have turned public activity into a type of business based on grant seeking and report writing.

REPRESENTATIVES OF SOCIETY

The concept of a civil society is an integral part of the contemporary understanding of democracy. Democracy means not only fair elections, formal procedures and mutual control of government agencies and politicians. It is also an opportunity for citizens to freely pursue their interests, develop their potential and exert sufficient influence on government officials. In fact, the government has to serve society by fulfilling state functions for its benefit. Citizens pursue their interests both independently and in groups which have the status of civil society institutions. In developed countries these institutions produce the lion’s share of new ideas that are generated by society as a whole. They perform social functions, organise civic mutual aid and interact with the government and business for the efficient and transparent solution of urgent issues. Intellectuals and think tanks play a crucial role in this system. They find new ways for society to develop and identify the true causes behind problems faced (or generated) by the government and business. They also serve as moral authority and intellectual centres for public movements aimed at improving the situation in the country.

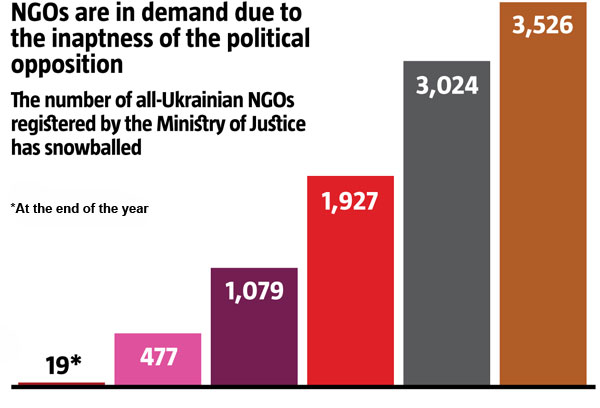

Officially, Ukraine has a number of such institutions. In 2011, nearly 50,000 NGOs (66 per cent of the total) and charity organisations (31 per cent of the total) were registered in Ukraine. Among NGOs, 18 per cent are sports societies, 15 per cent professional, 11 per cent youth, 9 per cent unions of veterans and invalids, 7 per cent cultural and educational, 5 per cent ethnic and 5 per cent human rights associations. By the end of 2011, there were only 3,500 all-Ukrainian organisations, of which around 500 were set up in the past two years.

This broad definition already points to a problem. It puts together under one umbrella the vestiges of the Soviet era (trade unions and “artistic unions”), public initiatives (organisations set up to solve specific problems or monitor government activities) and a number of others. Each of these categories is a topic that merits a separate discussion because most of them are not working to even try and approach their declared objectives.

However, most of the blame rests with associations of artists, scholars and experts that call themselves research, or analytical centres, and which should be an example for others to follow and serve as the intellectual and moral vanguard of society. These organisations have the potential to generate new values, standards and knowledge, as well as make clear recommendations on how to implement them in practice. But much will be required from everyone to whom much has been given.

WHO NEEDS AN INDEPENDENT OPINION?

Society has a demand for nongovernment institutions, and the more autocratic the government, the stronger the interest in alternative opinions is. Opinion polls carried out by the International Foundation for Electoral Systems in Ukraine (IFES) showed that 41 per cent of the respondents across the country pointed out the need to have NGOs in 2005, and this index had almost doubled (76 per cent) by 2011.

But the supply that would meet this demand is missing. There are both objective and subjective reasons for this situation. First, independent NGOs have limited sources of financing. Second, most of them were set up by professional grant seekers who have turned public activity into a type of private business.

Ukrainian legislation provides no palpable stimuli for entrepreneurs to make donations to NGOs. Unlike many developed countries, such donations do not bring any tax relief in Ukraine. Thus, NGOs have few ways of obtaining financing for their activities. First, they can apply for government financing. Second, they can convince business that they have a good reason to exist and that their products are useful. Third, they can obtain grants from international or foreign donors.

However, each option poses its own problems.

The government has to be interested in the development of independent thinking. After all, the governments of most developed countries sponsor universities and research centres to conduct fundamental and applied research. However, a mere 0.05-0.1 percent of the national budget has been allocated to support NGOs in Ukraine. And even these sums are distributed following the overall tendencies inherent in government purchases – with kickbacks up to 70 per cent and dividing up money among one’s “own men.” Moreover, officials often distrust NGO representatives, viewing them as “strangers” who are far removed from the real problems faced by public administration; and sadly the latter point is often true. It is easier for an official to organise a puppet “public council” attached to these agencies rather than interact with independent experts.

WHY SHOULD BUSINESS CARE?

Because entrepreneurs do not see stimuli to support public activity (in the absence of additional benefits, etc.), they must understand why they need the activity of specific organisations. On the one hand, it may be a kind of PR show of the “progressive nature” of their businesses targeting, and above all, a show for their Western partners.

This list includes the Foundation for Effective Governance (close to Rinat Akhmetov) and the structures and initiatives launched by Viktor Pinchuk (particularly, the YES forum in Yalta), Petro Poroshenko and others. The defining feature of these structures is the organisation of pompous events to show that their sponsors belong to “globally relevant circles.” For this purpose, Pinchuk brings celebrities to Yalta, while Akhmetov pays world-renowned experts to write “plans of national development” or “energy strategies.”

The main shortcoming of this activity is that it produces empty texts that are unfeasible to implement in reality and divert the attention and resources of society away from true problems. This, in particular, pertains to the mass media: journalists (even from periodicals that pride themselves on being objective and unbiased, such as Ukrainska pravda) attend these events and provide coverage. The combination of PR practices in hosting these events and their coverage in the style of a beau monde reception (largely without any criticism of the organisers or invited figures) turns the discussion of truly important problems into an exchange of self-introductions.

There are other, “mixed” options for cooperation between businessmen and NGOs. For example, Mykola Martynenko is believed to be a key sponsor of not only the politician Arseniy Yatseniuk, but also the Oleksandr Razumkov Centre. This organisation positions itself as being outside politics, and a large part of its budget comes from grants. However, the presence of “exclusive” business financing may set limits on freedom and independence, which may soon show through in the forthcoming parliamentary elections.

In contrast, there is an overall lack of examples when businesses and NGOs have civilised partnership relations. The problem is not only that businesses are unwilling to donate. The thing is that NGOs rarely have anything worthy of offering to potential donors. General recommendations in the style “If mice are not to be eaten by predators, they have to turn into hedgehogs” are of no interest to companies, while none of the numerous “centres” and “institutes” carries out truly high-quality applied research. The International Centre for Prospective Research is a case in point. In 2010, this organization received (and spent) money for 13 projects, but the efficiency of this feverish activity is next to zero: the public has not seen either deep research into problems of the economy and public administration, or any implemented recommendations.

FLOWERS ON CONCRETE

The most controversial way to support NGOs is attracting grants from international or foreign donors. It is controversial if only because they were the only source of financing for independent organisations during the first years of our independence.

The main grant-giving organisations are representations and special foreign aid structures of the USA, the EU, leading EU members, world-famous private donors (primarily George Soros) and several other organisations. Their role in the development of independent NGOs in general has been, and still is, crucial. The support provided by, for example, the Renaissance Foundation and Western institutions made it possible for NGOs to appear in the early 1990s. However, with time and the development of Ukrainian society a number of problems have piled up in the relationships between donors and associations of Ukrainian citizens.

The thesis, adopted by some supporters of the current government, that grant-giving organisations pursue “the interests of the West” to the detriment of Ukraine should be rejected immediately. Many proponents of these “versions” should themselves answer the question about how they spend the Russian financing that they receive (see The Ukrainian Week, Is. 9, 2011). Of course, foundations that are part of government organisations in specific countries promote their interests. A noncritical perception of such structures by certain grantees leads to strange cases. A textbook example is the superficial critical statements made by historian Yaroslav Hrytsak regarding the OUN and the UPA, which can only be explained by his cooperation with Polish foundations. However, as far as political issues are concerned, Western countries are objectively interested in the democratic nature (and thus stability and economic development) of Ukraine, which is exactly what our society wants.

The problems of a “grant-based” civil society lie elsewhere, and the biggest one has nothing to do with grant-givers at all. “Grant sucking” (uncritical acceptance of programmes, seeing funding as a self-sufficient goal, etc.) is not a Ukrainian term. But in democratic countries grants are an auxiliary, rather than the main, source of financing for civil society. In contrast, neither the government nor business in Ukraine supports NGOs for the reasons mentioned above. That is why grant-givers are forced to perform uncharacteristic functions. However, it is impossible in principle to secure the fully-fledged development of a civil society in a country of 45 million by distributing grants in the amount of $3,000-20,000 (and less frequently $50,000-100,000), for 6-12-month projects (in rare cases, longer).

What was necessary in the early days of independence leads to distortions now, 20 years later.

First, grant seeking has turned into private business. There is now a group of people (mostly in Kyiv and less so in the regions) who view grants as a source of their income. The main thing for them is to write reports on time and meet the deadlines for another grant competition. Hence there are thousands of “one-man centres” that obtain grants to carry out some empty activity of the brochure- roundtable-publication kind and write essentially useless documents. But they continue to win new grants. Certain activities (such as the publication of printed products) have turned into a source of additional income when a smaller-than-declared number of copies are printed, etc. A glance at a public report of any large donor reveals a number of “centres” and “institutes” that you can only learn about from this source. If organisations do not maintain quality control over products for which they pay, this kind of parasitism will continue to persist.

Another problem has to do with certain distortions in the way grant-giving organisations are involved in Ukrainian realities. For example, traditional grant consumers form a “support group” of sorts: they tell donors what they want to hear and receive additional funding in order to be completely reassured that their own versions are true. At the same time, lies cannot be ruled out.

Some organisations may seek more intimate relationships with certain government representatives.

For instance, one of the directors of the Institute of World Policy which gets the funding from the Think Tank Fund, International Renaissance Foundation, USAID and other donors, also heads the Institute for Nuclear Research which cooperates closely with entities linked to Andriy Kliuyev, member of the Party of Regions, Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council and, according to some experts, chief coordinator of administrative leverage and enforcement bodies at the upcoming parliamentary election.

The third and final problem is that donors are not sufficiently demanding enough in terms of who receives their grants. This turns their programmes into a kind of “losers’ tank.” For example, Oleh Rybachuk, who proved to be absolutely incapable of implementing any specific decisions as Vice Prime Minister for European Integration (2005) and Chief of the Presidential Secretariat, remains one of the most active receivers of grants. He and his team are associated with network initiatives such as “The new citizen” and others.

COOPERATION BETWEEN SECTORS

These and similar problems show that an attempt to build a civil society based exclusively on grants is like planting flowers on concrete. This vegetation will require constant monitoring and will become unviable as it demands increasing amounts of attention and resources. For civil society in Ukraine to develop without constraints, the concrete that shackles it should be removed in the first place.

Thus, it makes sense to pursue the objective of creating a transparent structure for the distribution of government-commissioned research among NGOs. It must be a part of reforming the system of government purchases, and associations of citizens should urge politicians to include guarantees to this effect in their pre-election programmes.

Another objective that could be pursued is getting entrepreneurs interested. Businesses, primarily medium and non-oligarchic large ones, and NGOs have to find common ground, the areas of common interest in which the former would be willing to invest resources and the latter intellect and the ability to find new (and real) answers to existing problems. In order to stimulate this search, it is possible to adopt a mechanism that is used in many Western countries. Entrepreneurs who are interested in making certain social changes happen could set up “supervision councils” to identify research areas and finance specific results.

Grant-givers – international, foreign and Ukrainian – could, on the one hand, look into supporting new organisations (until they prove their sustainability) and, on the other, participate in large-scale projects to develop systems of applied changes that our country needs if it is to attain European standards in specific areas. They could help prospective researchers, opinion leaders and public activists from Ukraine (especially those “on the ground”) to get acquainted with specific experiences in Western and other countries and focus this effort on supporting changes in Ukraine rather than their imitation.

CIVIC FICTION

According to the Institute of Sociology at the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 80 per cent of Ukrainians are not members of any NGO, even though Ukraine is almost on a European level in terms of the number of NGOs. The classical mafia-type union of large capital and government bureaucracy is utilising the absence of civil society in order to create an illusion that democratic institutes exist and to directly solve their own business problems.

“Ukraine has an entire system of puppet organisations that appear to be civic structures,” activist Serhiy Hendlevsky says. “They are set up by specific financial-industrial groups, entrepreneurs or even simply officials, who cannot be businessmen in our conditions, in order to protect their interests in the public domain. In general, this kind of thing also exists in the West. There is an entire network of fictitious NGOs there that are, in fact, financed by certain companies in order to influence public opinion by way of injecting certain statements and topics into public discourse. It is especially characteristic of the pharmaceutical and environmental spheres. However, this drawback is offset there by the overwhelming majority of bona fide NGOs that bring together true activists genuinely interested in their cause. In contrast, most NGOs in Ukraine are directly linked to donors or are even set up by them. They also have close contacts with spin doctors who work for politicians and keep a low profile. There are also a number of NGOs that do not work constantly for one client but simply sell their services in carrying out certain campaigns.”

According to information obtained by The Ukrainian Week, an entire network of such organisations is attached to Ukraine’s Cabinet of Ministers and the Verkhovna Rada. Their main objective is to act on orders from above and insert certain desired statements in public discourse, initiate draft laws, criticise opponents and sustain the necessary level of attention to and the discussion of topics in which their clients are interested. Heads of such NGOs are most often front men or, quite openly, assistants to MPs or employees of government ministries. These organisations are especially common in social spheres that are not associated with financial benefits and large money flows – sports, medicine, education, social policy, etc. In contrast, clients from “rich” ministries – finance, coal mining and economy – prefer to keep their puppet expert centres and analysts working at full string.