In March, Ukrainians mark the foundation of Carpathian Ukraine, the autonomous political entity within Czechoslovakia that boldly declared independence on March 15, 1939, surrounded by adversaries. In the lead-up to World War II, Carpathian Ukraine stood resolute against nations asserting the “might makes right” to subjugate and dismantle entire nations and peoples.

Facing Hungary, supported by Germany and Italy, and bolstered by Poland’s backing of Hungary, Carpathian Ukraine’s defiance even unnerved Stalin. The young state’s leaders, champions of Ukrainian unity, posed a threat to occupiers’ colonial ambitions, embodying the aspirations of a united Ukrainian nation. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, Carpathian Ukraine’s resilience stemmed from the organic growth of a conscious Ukrainian identity on this historic Ukrainian land. A testament to Ukrainians’ ongoing quest for self-determination, Carpathian Ukraine symbolized the enduring relevance of their national liberation efforts from 1918 to 1920.

“We are part of the Ukrainian people”

To truly understand the importance of Carpathian Ukraine during the years 1938-1939, we need to go back two decades. Just a week after the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR) declared independence on November 1, 1918, events unfolded in the Ukrainian lands along the southwestern Carpathian Mountains slopes. These events highlighted the unwavering identity of the local Ukrainians despite centuries of Hungarian colonisation and assimilation efforts. Holding onto their ancient ethnonym “Rusyns” (Latin: Rutheni), the Ukrainians of this region made an explicit declaration of their affiliation. On November 8, 1918, the Rusyn People’s Council in Stará Ľubovňa, followed by the Rusyn People’s Council in Svaliava on December 8, and then the Maramorosh Rusyn People’s Council in Sighet on December 18, all proclaimed their unity with Ukraine. Only the Rusyn People’s Council, founded on November 9, 1918, in Uzhhorod, advocated for autonomy within Hungary.

A significant milestone in the struggle for the unity of Transcarpathian Ukrainians with the rest of Ukraine was the establishment of the Ukrainian Hutsul Republic from November 8, 1918, to June 11, 1919, under the leadership of President Stepan Klochurak. Later, he would serve as a deputy in the Sejm of Carpathian Ukraine and as its minister. Klochurak addressed the public in one of his speeches:

“Long before the war, the Hungarian ruling elite sentenced us to national demise. They stripped our people of the right to have their own cultural organisations, even banning our children from learning in their native language in church schools. […] We’ve always been aware of our place within the Ukrainian people. Our kinship was never forgotten by our people despite centuries of being cut off from our brothers.”

Prominent spiritual figures of the Ukrainian revival movement of Carpathian Ukraine: Greek-Catholic priests Dmytro Popovych, Sevastian Sabol (Basilian monk), Bishop Dionysius Nyaradiy, and Polikarp Bulik (Basilian monk). Author unknown. Photo: Public domain

On January 21, 1919, the General Assembly (Congress) convened in the city of Khust, led by Mykhailo Brashchayko and comprised 420 delegates – one for every thousand of the population. They unanimously voted in favour of joining the Ukrainian People’s Republic, which had been established in 1917.

Following this, the political landscape unfolded in a manner that once again left the Ukrainians of the Transcarpathia to choose the lesser of two evils. Seeking to avoid a return to Hungarian rule, and after consultations with the diaspora in the U.S., amidst the occupation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic by Bolsheviks and the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic by Poles and Romanians, they agreed on May 8, 1919, to unite with Czechoslovakia. This decision was supported by arguments such as its Slavic character and Prague’s promise to grant autonomy to the Ukrainians. This pledge was officially enshrined in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on September 10, 1919.

However, upon becoming part of Czechoslovakia, the Transcarpathian Ukrainians did not receive justice. This was because the Ukrainian ethnic territories west of the Uzh River valley were ceded to Slovakia. As a result, the Ukrainian-populated region, which had been promised autonomy, was limited to the historical counties of Maramorosh (excluding its southern part and the city centre of Sighet), Ugocsa (excluding its southern part), Bereg (excluding its southern part), and Ug (excluding its southwest part).

Later, the Slovaks even claimed Uzhhorod, and Avgustyn Voloshyn, serving as a parliament deputy and one of the Ukrainian leaders, had to expose these aspirations. Adding insult to injury, Prague’s government chose the name “Subcarpathian Rus” for the Ukrainian region, a neologism from the 1870s coined by the Russophile Adolf Dobryansky, rather than “Transcarpathia”, a term that had been in use since the 1830s.

“Divide et impera”, or its “democratic” variant by Ukraine’s “Slavic brothers”

In their quest to form the “Czechoslovak” nation, the elites of the new state, proudly claiming to be the “most democratic” in this part of Europe, resorted to colonial tactics aimed at assimilating Ukrainian Transcarpathia. It wasn’t just about the salt extracted in Solotvyno, sent as raw material for milling in Olomouc, only to return and be sold at a higher price as a product. Nor was it solely about the Transcarpathian wood being shipped westward for processing rather than being processed locally.

The crux of the matter lay in the context of the division among the Ukrainian elites of that era. There were the Russophiles, often dubbed as “Russians,” and the Ukrainian Narodovtsi, or the Populists. The Czechs, wary of bolstering the latter, placed their bet on Russophiles.

With the rise of local “Russians” aided by immigrants from the former Russian Empire, particularly the chauvinistic Russian White Guards, the people of the Transcarpathia found themselves pressured to adopt the Russian language in schools. Moreover, instead of the heavily Magyarized Greek Catholic Church, they were encouraged towards Orthodoxy imbued with a “Russian spirit.” These were the consequential byproducts of Czech panslavism and Russophilia.

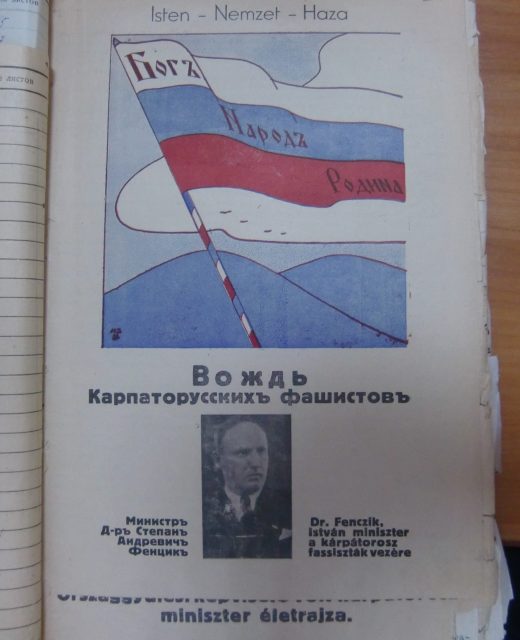

Agitation leaflet of Stepan Fentsyk, one of the leaders of the Russophiles of Zakarpattia, “leader of the Carpatho-Russian fascists”, a Magyaron, and Minister in the government Andriy Brodiy. Photo: Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine in Zakarpattia region

Over two decades, the Czechoslovak authorities exploited the opposition between the Ukrainian Populists and Russophile factions to evade their promise of granting autonomy to the Transcarpathia. Czechoslovaks’ excuses were predictable: the local populace wasn’t deemed ready for self-governance, and the question of power transfer remained elusive due to societal divisions. The state simultaneously discriminated against Ukrainians, depriving them of the chance to gather administrative experience even within local administrations.

“After a decade under Czechoslovak rule in the Transcarpathia, where Czech presence was nearly absent before 1918, the government apparatus consisted of 80% Czechs,” wrote Sevastian Sabol, a Ukrainian Basilian monk, poet and writer. By 1927, out of all 2262 civil servants in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, only 301 were Ukrainians.

This continued until the Ukrainian Populist faction, with the growing rise of Ukrainian national identity, prevailed over the Russophile faction in the mid-1930s. In 1929, during the First Congress of Youth in Uzhhorod, Leonid Bachynsky, a Ukrainian writer, journalist, public figure, and educator hailing from present-day Dnipro, publicly referred to the region as “The Zakarpattia Ukraine” (Transcarpathian Ukraine). This led the Czech authorities to expel him from the country.

However, the process of asserting Ukrainian identity continued, reaching a turning point with massive protests against the ban imposed by regional president Antonin Rozsypal on the public use of the blue-yellow flags. In 1934, Ukrainian youth from across the region gathered for their Second Congress of Youth in Mukachevo. Despite the ban, they defiantly marched with blue-yellow flags. The event drew over nine thousand participants, showcasing the growing strength of Ukrainian national identity. The ban on the Ukrainian flag, viewed as a direct repressive response by the Czech administration, lasted for five months.

The Munich Agreement and its consequences

Ukrainian identity in the Transcarpathia was gradually maturing towards independence. This transformation is exemplified in the life of Ukrainian leaders, particularly Avgustyn Voloshyn. Initially influenced by Russophilia, Voloshyn gradually shifted. By closely observing the lives and needs of the local Ukrainian population, he developed a strong Ukrainian identity, eventually becoming the symbol of it. The generation to which Voloshyn belonged, along with those that followed, transitioned from identifying as “Hungarian Rusyns (Ruthenians)”, an ethnographic minority, to embracing their Ukrainian identity. Members of these generations not only witnessed this shift but also reflected upon its significance.

Sevastian Sabol explained: “Educated in Hungarian, and later in Moscow-oriented schools, once I myself was one of those disheartened Rusyns, for a long time stubbornly torn between Budapest and Moscow. Only when I began to delve into the history of my own people, into its glorious past, its language and culture, did I see that we have no reason to consider ourselves less valuable than other nations […] We, the Rusyns, are children of the great Kyivan Rus-Ukraine […] We are also Ukrainians, just like those beyond the mountains in the Galicia and along the Dnipro, where the golden-domed Kyiv stands […]”.

As the ambitions of neighbouring powers, especially Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler and its ally, Hungary, led by Miklós Horthy, grew, Czechoslovakia found itself in a precarious position. On September 30, 1938, Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy signed the Munich Agreement, which forced Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland to Germany, leaving it vulnerable to Berlin’s influence. The lesson drawn was from the unrealistic hopes of the then British Prime Minister and self-proclaimed ‘peacemaker’ Neville Chamberlain. Upon his return from Munich, he stood in front of his residence at Downing Street 10 and declared: “Dear friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time. From the bottom of my heart, I thank you. Go home and get a good, quiet sleep.” This appeasement of dictators by Western leaders ultimately set the stage for World War II. The Munich Agreement caused a crisis in Czechoslovakia but made autonomy achievable for the Transcarpathia. The country was forced to become a federation of Czechia, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia – Carpathian Ukraine.

The compromise and the Russophiles’ betrayal

Drawing on his political acumen and foreseeing significant changes, Avgustyn Voloshyn reinvigorated the First Central Ruthenian (Ukrainian) People’s Council in August 1938, an institution that had its roots in the liberation struggles of 1918–1919. Within this council, Ukrainians and local Russophiles agreed on a temporary unity to demand autonomy, first on October 8 in Uzhhorod and later in Prague. The Council’s initial Prime Minister, Andriy Brodiy, the Russophile, upon his appointment, vowed to steer the people to a “safe haven.” Yet, not everyone, especially in Prague, grasped that his intentions pointed towards Hungary. Surprisingly, within two weeks, the Prime Minister was arrested on charges of treason in favour of Hungary.

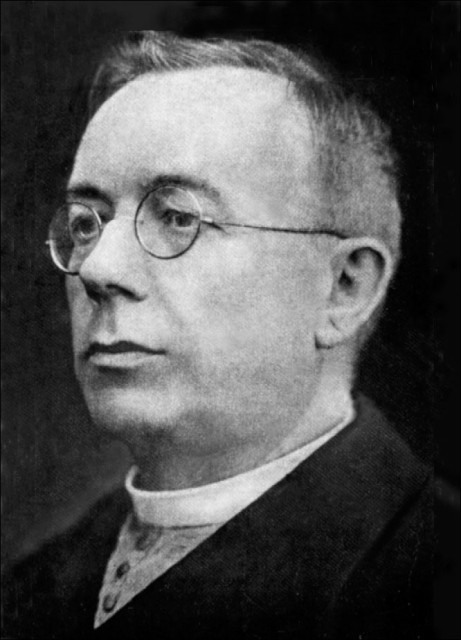

Avgustyn Voloshyn, Greek-Catholic priest, educator, patron, public-political figure, President of Carpathian Ukraine. Photo: Public domain

Despite everything, a new government led by Avgustyn Voloshyn was formed on October 26, 1938. The following day, the Nova Svoboda newspaper published an appeal from the Ukrainian People’s Council, stating: “We believe that the great 50-million Ukrainian people will continue to raise their powerful voice and will not allow our eternal enemies to impose shackles on us again.” The Ukrainian agenda for autonomy took a prominent place. The idea of Ukrainian unity in the development of the Transcarpathia was the backbone that held everything together.

First Vienna Award: Ukrainians stood firm

The elation of achieving Ukrainian sovereignty had barely settled when the Transcarpathia was dealt another blow. On November 2, 1938, a forced the First Vienna Award by Germany and Italy compelled Czechoslovakia to yield a portion of its territory to Hungary. This loss amounted to approximately 12% of Ukrainian autonomy’s land, with estimates ranging from 1500 to 1700 km2, including the key cities of Uzhhorod, Chop, Mukachevo, and Berehovo. However, this setback did not crush the Ukrainian spirit: they evacuated as much as possible from the occupied areas and established the new capital in Khust. On November 4, the First Ukrainian People’s Council issued a manifesto, which concluded: “Ukrainian People of the Transcarpathia! Take pride in the responsibility of laying the foundations of our state. Trust in your leaders – the First Ukrainian (Rus’) People’s Council, believe in the power of your people, who, with the strength of a courageous army, lead you towards a glorious future. Be resolute, and through your hard work and sacrifice for the Ukrainian people, demonstrate that you have evolved into a nation capable of shaping its own destiny.”

Resistance to the emancipation of Transcarpathian Ukrainians persisted in Prague, and it wasn’t until November 30, 1938, that the central government permitted the use of the term “Carpathian Ukraine” – on condition that it could also be referred to as “Subcarpathian Rus.” In practice, though, “Carpathian Ukraine” took precedence.

In response to the call of Carpathian Ukraine in the years 1938–1939, Ukrainians from various regions, especially from Galicia, Volyn, Polissia, and even the diaspora, rallied to the cause. During Carpathian Ukraine’s parliamentary elections held in February 1939, nearly 92,4% of the voters demonstrated their trust in the leadership of Carpathian Ukraine, especially Voloshyn, who led the Ukrainian National Association. Meanwhile, Hungary was crafting new plans to occupy Carpathian Ukraine. The first plan was set for the night of November 19–20, 1938, followed by another on February 12, 1939. However, on both occasions, the Hungarians were held back by Hitler, awaiting the opportune moment to dismantle Czechoslovakia. That moment came when Slovakia declared its independence on March 14, 1939. Under the guise of maintaining peace, Germany occupied Czechia, while Hungary took control of Carpathian Ukraine.

Resisting the occupation

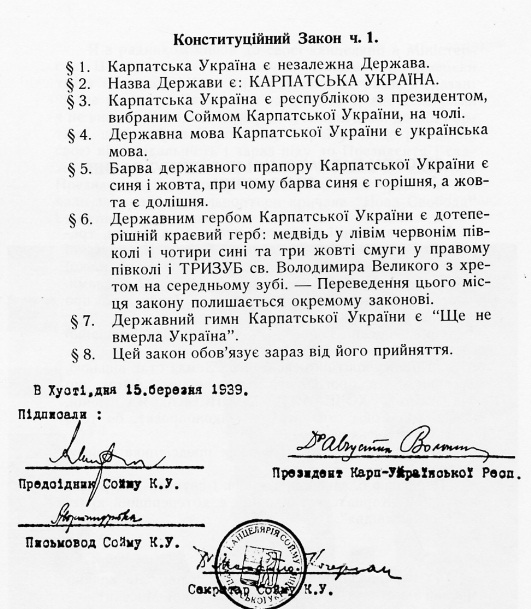

The Ukrainian state fiercely resisted the occupiers despite the fact that its Organisation of National Self-Defence, Carpathian Sich, had not yet evolved into a full-fledged army, remaining a paramilitary organisation. Amidst the thunder of cannons, the Soym (Assembly) of Carpathian Ukraine in Khust passed a Constitutional Law proclaiming the state’s independence. The Ukrainian language, the blue-yellow flag, and the anthem “Shche Ne Vmerla Ukraina” (Ukraine Has Not Yet Perished) were proclaimed the new state’s official symbols. Avgustyn Voloshyn was elected president, with Augustin Stefan chosen as the head of the Soym.

The building of the state gymnasium in Khust, where the Parliament of Carpathian Ukraine declared its independence. Photo: Public domain

On March 16, Hungarian forces seized Khust, and by the 19, they claimed the capture of the entire Carpathian Ukraine, although pockets of resistance persisted until May. The Carpathian Sich suffered approximately 1,500 casualties, including killed, wounded, and captured members. Subsequently, the Hungarians executed around 4,500 Ukrainians from the region. The government of Carpathian Ukraine was forced into exile, yet the occupation forces felt uneasy and spread rumours of Voloshyn’s imminent return.

Hungary maintained control over the Transcarpathia until October 1944, when Soviet forces pushed them out. It is noteworthy that even the Communists, as they established their authority in this Ukrainian region, sought to leverage its reputation for their own legitimacy. They even adopted the name “Transcarpathian Ukraine” for the region. However, in reality, they, much like their predecessors, began to dismantle any signs of Ukrainian identity that did not conform to their ideological agenda.

Constitutional Law No. 1 of Carpathian Ukraine, proclaimed on March 15, 1939. Photo: Public domain

In historical literature, claims sometimes surface that Transcarpathian Ukraine aligned with Nazi Germany. However, an analysis of the events of 1938–1939 and the subsequent years debunks these claims. Firstly, following the cui prodest principle, it becomes clear that Hitler’s policy mainly benefitted his ally, Hungary. Secondly, Germany strategically used the Carpathian Ukraine in its complex geopolitical manoeuvres against Poland, Romania, the USSR, and even Hungary itself. The idea of autonomous Ukraine was especially vexing to Stalin. Consequently, during the 18th Congress of the Communist Party on March 10, 1939, the first following a period of great terror, Stalin declared that Carpathian Ukraine was a fabrication of Great Britain and France designed to create discord between the USSR and Germany.

The subsequent joint actions of Hitler and Stalin, especially against Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland, exposed the systematic “collaboration” between these tyrants against their targets. Romania, despite its neutrality concerning Carpathian Ukraine, witnessed Poland’s ruling elites succumbing to the allure of joining an aggressor club, driven by their anti-Ukrainian policies and fear of any potential Ukrainian state. This compromised Poland’s later claims of being exclusively a victim of the Second World War. Following the Munich Agreement, Poland seized the Zaolzie region from Czechoslovakia. Later, it took the tiny mountainous area, Jaworzyna from Slovakia and, at Hungary’s proposal, participated in targeted and well-planned acts of terror against Carpathian Ukraine. These policies naturally led to logical consequences: great powers (Germany and the USSR) devoured smaller ones, only to clash with each other later on. It is worth noting that Carpathian Ukraine’s appeal to Germany to guarantee its independence, even during the time of Hungarian armed aggression, was not an orientation towards Berlin but rather a desperate attempt to survive.

Amidst the chaos of the Second World War, the President of Carpathian Ukraine and his compatriots faced a moral dilemma and opted not to collaborate with the Nazis, fascists, and their allies, unlike some of their neighbours. Notable figures of Carpathian Ukraine, such as Ivan Rohach, Ivan Roshko-Irliavsky, Vasyl Kuzmyk, and others, who championed the idea of a united Ukrainian state, perished in Kyiv. After his exile, President Voloshyn settled in Prague, where he worked at the Ukrainian Free University. In May 1945, a counterintelligence unit of the USSR’s People’s Commissariat for Defense, SMERSH, arrested Voloshyn and took him to the Soviet Union. He was pressured to support the establishment of a communist regime in the Transcarpathia, but he rightly saw the Soviet presence as an occupation. Following mistreatment and interrogations, Voloshyn passed away in the Butyrka prison on July 19, 1945. He remained steadfast in his ideals and values. In 2002, he was posthumously awarded the title Hero of Ukraine.