Despite the desperate attempt of Ukrainians to recover their statehood, the first war of independence was defeated while the territory of Ukraine ended up being divided between four states. But the statehood faded slowly and different communities still harbored the last hopes for an insurgency in the Dnipro Ukraine or a compromise decision of the West on Halychyna.

In the meantime, Ukrainian society changed significantly. The fact that Ukrainians acquired huge experience of war in Ukrainian military formations was a crucial one. This was especially visible in people from Halychyna where they had avoided professional military service at any cost before the war of independence.

“Our public hated military uniforms as much as it hated prison rags,” writer Andriy Chaikovsky wrote in his memoirs. “Mothers would throw a fit whenever their child ended up in the army.” According to Austrian laws, an officer could only marry a rich bride. This meant that military service automatically withdrew a young man from his national group.

With the war of independence, even if short, over 100,000 people went through the Ukrainian Galician Army. A huge number of those eventually found themselves in Polish internment camps. An official report from the Polish Ministry of Military Affairs dating back to November 1920 mentioned 70,000 war prisoners. Ukrainians were not the only group but reports from different camps showed that they were the majority. A December statement mentioned the disarmament of up to 30,000 of “Petliura’s people”. Given those numbers and war experience one could expect that combat groups would emerge eventually, and they did.

The cause of Spilka, the Union

It was impossible to count how many underground structures the military set up. But one eventually grew into the large and effective Ukrainian Military Organization, known more informally as Spilka, the union in Ukrainian. The breaking point came on September 25, 1921, when UVO member Stepan Fedak attempted to assassin Polish Chief of State Jozef Pilsudski in Lviv.

The issue of where Halychyna would belong was not yet solved on the international arena by then. So virtually the entire Ukrainian population was in opposition to the Polish occupation regime. Fedak’s shot, numerous arrests and the flow of sympathizers joining UVO turned it into the major revolutionary force in Western Ukraine.

RELATED ARTICLE: The forging of unity

One of the main factors in the popularity of UVO was its leader Yevhen Konovalets, an activist in the student movement of Halychyna before the war and commander of the Kyiv Sich Riflemen during the war. His Sich Riflemen friend Andriy Melnyk and Konovalets himself married the Fedak’s sisters. At the time of Fedak’s assassination attempt their father was one of the most respected Ukrainians in Lviv and chairman of the Committee of Ukrainian Residents, an entity representing Ukrainians in relations with the Polish authorities. The police wrote in its files that the marriage gave Konovalets “access to the political circles of the region”. Shortly after the assassination attempt, the UVO leader emigrated.

The second attempt to assassinate the chief of state took place at the Eastern Trade Fair, an international expo in 1924. An UVO militant threw a bomb at the vehicle with Poland’s president Stanislaw Wojciechowski. That attempt failed as well, but the Poles learned their lesson. When Ignacy Moscicki, the president of Lviv Polytechnic University, was elected head of state (1926–1939), he avoided visiting Lviv.

The burial of Tadeusz Holowko in 1931. He was a Polish politician known as a Ukrainophile killed in an attentat by a Truskavets unit of the OUN at a Ukrainian resort. Ukrainians were then pressing the League of Nations to hold Poland accountable for its pacifications. Neither the Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists nor the local leaders probably knew about the assassination plans

Meanwhile, Western states made the ultimate decision to transfer Halychyna to Poland in March 1923. Ukrainian politics changed: the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR) government in exile led by Yevhen Petrushevych moved to a sovietphile position and political parties emerged in the “borderland”, i.e. Western Ukraine. The former caused a slight divide in the UVO turning it into a militant group without political leadership. The latter allowed members of the underground movement to legalize themselves through party activity. This had been unthinkable just a year earlier. In 1922, politician Sydir Tverdokhlib was shot for his participation in the election campaign.

Now, the UVO Leadership Team believed that it would manage control or at least coordinate Ukrainian political life. That expectation was futile: many leading members distanced themselves from the revolutionary activity, opting for party work instead.

Young members could replace them to some extent. Two students – one was Roman Shukhevych – shot the curator of education in Lviv in 1926 in protest against Polonization. But the youth had limited access to the UVO, so the gymnasium students created their underground groups on their own. Experienced UVO members had influence on them, yet the emergence of new organizations expanded the range of revolutionary structures. The same developments were taking place in the rest of Europe.

“In addition to that, Ukrainian nationalist movement began to shape,” UVO member Osyp Boidunyk stated. “It could grow into a serious competitor for the UVO, especially abroad. The Dnipro Ukraine element began to stand out and dominate in it. It was not linked to the UVO organizationally and the UVO lacked any element of it. This absence of it in the UVO bothered Yevhen Konovalets, especially as his plans included intensification of the campaign across Ukraine under the Bolshevik Moscow occupation.”

The idea to unite into the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists emerged in talks between the leaders of different structures.

On the path to Vienna

In November 1927, the I Conference of Ukrainian Nationalists took place in Berlin where 15 people established the Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists (LUN) led by Konovalets, followed by a decision to hold the Congress to unite all organizations.

“A body emerged beyond the existing nationalist groups that had to stand above us as the highest entity of the whole nationalist movement. The creation of it did not come from the grassroots level through elections, but from the top without elections based on an agreement between several individuals,” conference attendee Volodymyr Martynets described the establishment of LUN.

Not everyone welcomed that scenario. The II Conference took place in spring 1928 in Prague before the Congress where nationalists distanced themselves from the legal political movements: “The Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists distances itself from all Ukrainian political movements and does not enter into cooperation with them. All organizations of Ukrainian nationalists in Ukrainian lands and abroad must step on that path,” the first resolution of the Prague conference stated.

The unifying Congress was scheduled to take place on September 1, 1928. Little time was left for organization, and the next date of December 1 was unrealistic. The ultimate decision was to have the Congress between January 28 and February 3, 1929, for the 10th anniversary of the Unification Act.

While Konovalets was heading to the Congress with an idea of uniting with other organizations, his biggest problem was with his local UVO members and their conflicting opinions on the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). While some wanted close cooperation with the political parties, the others together with the Union of Ukrainian Nationalist Youth (UUNY) decided to disrupt that scenario and demanded that Konovalets turned the organization into a military dictatorship.

The first list of invitees to the Congress had to be revised. Eventually, Ivan Kedryn, the political editor of Dilonewspaper and member of the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance, was the only representative of the camp supporting legal activities. Invited as a guest, he joined the closed-door consultations with representatives of regional sections where Konovalets acted as a silent arbiter. “The entire meeting had to reveal to Col. Ye. Konovalets the confrontation of diverging views. Therefore, he did not share any conclusions with us, nor approbations or rejections of conflicting views,” Stepan Lenkavsky from the UUNY mentioned in his memoirs. “Col. Ye. Konovalets had the skill to respectfully diffuse deep conceptual differences in a way that left neither side with a sense of triumph or defeat.”

The position of young representatives of regional sections won. “The Congress outlined the new organization framed along our interpretation of the nature of OUN. Col. Ye. Konovalets chaired the organization but did not agree to become a military dictator over us. We forgave him that very soon,” Lenkavsky wrote in the memoirs.

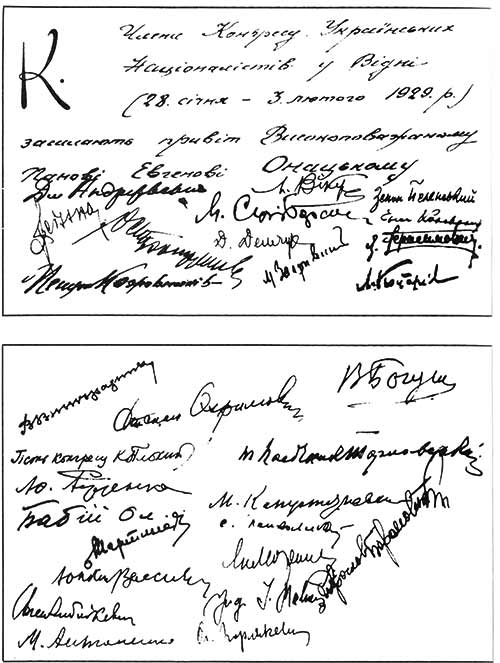

One of the two cards signed by the attendees of the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (28.01–03.02.1929). One ended up in the hands of the police sending six Congress attendees to court in 1932. Five got four years in jail

But the situation seemed far more complex than that: once the position of “politicians” in the UVO was defeated, representatives of emigre organizations were to be appointed before the revolution. These included people who had spent years away from Ukraine and felt perfectly comfortable in their new countries. The difference in their circumstances was illustrated by the Congress that took place under special security rules.

The delegates did not find out where the Congress would take place until right before it when they were told to come to Prague and sent to Vienna with fake documents. In Vienna, they settled in a small hotel where the meetings took place. They were banned from leaving the hotel or talking in the corridors in the first days. Suddenly, someone sent a greeting card around the room asking attendees to sign it. “This is not right because we are not on a tour in the mountains from which we could send greetings. But once the Colonel signed it, maybe the card would not be sent by post and would end up in specific hands,” an UVO member said in the discussion between representatives of regional sections. They did sign that card, and the next one. After the Congress, they took a photograph together.

Two years later, the signed card ended up in the police. Six members of the Congress ended up in court and got four years in jail for their participation in the Vienna meetings.

Dictat of the young

The Congress opened a new page in the history of the nationalist movement. Yevhen Konovalets visited the United States that same year as the newly established organization could expect more support from Ukrainians there than a militant group like the UVO. Konovalets himself tried to change his image of a pro-German politician. He was criticized for living in Germany, the sinner of World War I.

He settled in Switzerland with his family while nationalists were receiving funds, passports and diplomatic support from the Lithuanian government. Surma, the main print outlet of the UVO, relocated from Lithuania to Germany. The Lithuanian funding from Kaunas and Ukrainian funding from the US allowed the OUN to get back on its feet. But the internal situation was far more complex than what it looked like to an external observer.

The youth in Ukraine was becoming uncontrollable and active beyond expectation. In the early 1932, OUN’s outlet Rozbudova natsii(Building the Nation) published an official declaration of its emblem, a trident with a sword, and the anthem, We Were Born in the Great Hour (March of the New Army from 2018 – Ed.). Despite its militarist symbols, the leadership of nationalists was not so revolutionary. Part of it was outraged when it learned of the assassination of Emilian Chekhowsky, head of the U-unit for Ukrainian affairs at the Lviv police in March 1932. In a long series of assassinations committed by the OUN, including of a soviet consul, a Polish minister and a director of Ukrainian gymnasium, the murder of the main policeman dealing with the underground movement was probably the most logical and easy to explain. But it was that assassination that triggered a storm of discussions.

“The OUN does not use terror in politics or tactics. The leadership never authorized anyone to commit acts of terrorism. Now and before, Polish officials have been presenting the OUN as a terrorist organization which it isn’t,” said a draft statement of the Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists on the murder of Chechowsky. It was Konovalets who botched that statement. In his sharp letter to the Leadership, he dotted all i’s about the position of young revolutionaries in Ukraine: “In your letter, you put yourself and the whole Leadership of Ukrainian Nationalists on a pedestal of actual leadership which it is not in practice for different reasons. We initiated the organized nationalist movement, we helped it take shape, we are injecting it now but we are not leading it. I, too, start having doubts about whether we will succeed in leading it, despite our best intentions. It is possible that as the movement evolves, someone will take over leadership and lead it further on… In the Western Lands, this movement grows increasingly radical more than some of us wish. We cannot exclude a near prospect where we will find ourselves against that movement, in the role of parents, with no ultimate influence on its further development. Therefore, as people regarding ourselves as the Leadership, we should be aware that we might find ourselves in an unpleasant situation in the near future. The young nationalist movement in Western Lands does not tolerate us. But I’m sure that it will create its own leadership as it grows stronger and more organized internally unless we try to find a compromise.”

RELATED ARTICLE: A noble identity

Konovalets learned his lesson from the experience of Yevhen Patrushevych. In Konovalets’ words, Petrushevych “was sitting in Vienna and believing that he was the great dictator and that all of his orders had to be executed immediately”. As the leader of the Ukrainian sections of the OUN, Konovalets had a far more sober mindset and avoided movements “that would only be mocked locally, by the local nationalists”.

The revolutionary organization into which the OUN had morphed moved along the trail laid by the local members. The relations of the emigre and local sections got better. Konovalets was the only largely keeping that balance with his undeniable authority as an arbiter between different sides. “This was a paradox of sorts, that someone who was not extremist himself stood at the helm of an underground revolutionary organization,” wrote Ivan Kedryn about Konovalets.

The OUN leader was patient about every aspect of his position. He was eventually evicted from Switzerland and he lived his last years in Rome. The role he played in the nationalist movement was obvious to both OUN members and to its bitter enemies.

When Pavlo Sudoplatov, the future assassin of Konovalets, met with Stalin, he wrote Stalin’s words in his memoirs: “Our goal is to behead the movement of Ukrainian fascism ahead of the war and to force these bandits to eliminate each other in a struggle for power.”

The murder of Konovalets in 1938 and a new geopolitical situation caused by World War II did provoke a split in the OUN along the divide between the local members and the emigre part. But in its first decade, the OUN was a relatively solid foundation on which both of its split-offs, the Banderite and Melnyk wings, established independent and self-sustaining organizations.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook