The study “The Rights of the Imprisoned in Ukraine in 2010”, jointly carried out by NGO Donetsk Memorial with specialists from the Penitentiary Association of Ukraine, which spanned 2010 and the first half of 2011 showed a sharp deterioration of prison conditions in the Interior Ministry system and the State Punishment Enforcement Service as compared to 2005-2010. According to social surveys conducted by human rights organisations, the number of people who experienced violence at the hands of the police rose by nearly 30 per cent from 604,000 in 2009 to 780,000-790,000 in 2010, while the number of deaths nearly doubled (from 23 to 51). These indices correlate well with the weakening of civic monitoring of prison conditions.

ONE STEP FORWARD, TWO STEPS BACK?

In 2005-2010, the Ministry of Internal Affairs set up civic councils to secure human rights within its structure and its regional directorates, as well as mobile groups to monitor temporary detainment facilities, rooms for pre-charge detention in police stations (popularly known as “monkey cages”) and remand homes.

Having representatives of the public on their teams, these groups were quite active, according to human rights activists. They made over 900 trips in 2006-2009 (306 in 2009) to special institutions run by the Interior Ministry. On each trip they checked prison conditions and demanded internal investigations if violations were detected. As a result, seventeen temporary detention facilities in which norms were violated were closed.

Another body important for counteracting abuse was the Directorate for Human Rights Monitoring set up as part of the Interior Minister’s apparatus in 2008.

However, when power changed hands in 2010, the situation went downhill. One of the first things the new Minister of the Interior, Anatoliy Mohylov, did was to disband the abovementioned Interior Ministry directorate. Mobile groups were able to make a mere 12 trips to penitentiaries in the first three months under the new minister (March-May 2010).

Conditions in pre-trial detention units (known as SIZO) also deteriorated. The European Court of Human Rights received 19,950 applications from Ukraine in 2010 and 23,750 in 2011. According to the 2010 report by the government’s point man for the European Court of Human Rights, a large part of the complaints had to do with violations of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms regarding people who were detained or imprisoned – from limitations in correspondence to torture in pre-trial detention units and refusal to provide medical aid.

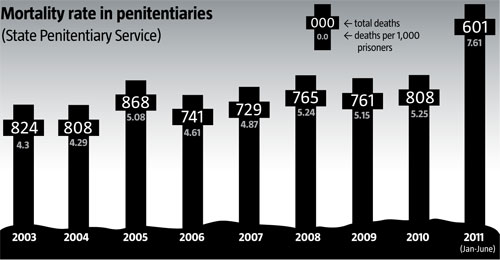

According to human rights activists the situation with medical care was especially critical. The abovementioned study says that the Lukianivka Pre-Trial Detention Unit has a mere 42 beds for the 3,000 people kept there and the situation in many other such units is even worse. According to certain sources, only inmates that receive material and financial aid from the outside can afford to stay in the medical department. The system is simply unable to provide efficient medical care for all suspects. As a result, the mortality rate in penal institutions has surged: 761 deaths in 2009, 808 in 2010 and as many as 601 in the first six months of 2011. Failure to provide medical aid may be qualified as torture of suspects and convicts.

CONTRARY TO THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE

Under Article 11 of the Law “On Pre-Trial Detention”, each detained person must have a space of at least 2.5 square metres (4.5 sq m for a pregnant woman or a woman with a child) in a pre-trial detention unit cell. The norm is somewhat higher in penal colonies: former President Viktor Yushchenko signed a law to increase it from 3 to 4 sq m before stepping down. According to UN recommended standards, pre-trial detention facilities should have at least 4 sq m per inmate. However, even the effective norm of 2.5 sq m is often violated due to overpopulation in some regions. For example, with a norm of 2,850 inmates, Kyiv has 37 per cent (1,058 persons) more than it should in its pre-trial detention centres, while Donetsk has 2,898 inmates instead of the permissible 1,970.

But the problem is not only a lack of space. Human rights advocates say that pre-trial detention is not so much a preventive measure as a way to put pressure on the accused. It is very convenient for an investigator to keep a suspect in a pre-trial detention facility: he or she is always “close at hand”, more susceptible to pressure and easier to frame up. Remarkably, 14,412 (22.3 per cent) were released from pre-trial detention facilities in 2010 of which 5,942 were freed owing to the fact that courts delivered verdicts without any prison sentence and 2,540 because the preventive measure was mitigated. Almost 8,500 people could essentially remain on recognisance not to leave rather than behind bars. This would free more money to spend on staff and pay damages according to decisions of the European Court of Human Rights. Finally, it would be much more humane with respect to citizens who have not been found guilty. Moreover, there is a worldwide practice of using hi-tech devices (such as bracelets) to track the location of suspects.

Pre-trial units are also actively used against political prisoners. More than 20 inmates can be said to have experienced serious pressure in SIZOs in modern-time Ukraine. For example, there was the high-profile case of Hanna Sinkova who was detained after cooking eggs on the ‘Eternal Flame’ (a permanent gas flame monument) at a war memorial in Kiev in protest against the government diverting budget money from its specified targets. Opinions may vary as to her deed – and this form of paying tribute to the dead – but the fact that a 19-year-old from a family of intellectuals was arrested and spent several months in a SIZO defies common sense. Moreover, Sinkova had never been charged with a crime before and came to interrogations without fail. At the same time, even a person suspected of a murder can avoid being put in a SIZO. But to do so, he or she needs to have close links to people in high offices. A case in point is Serhiy Demishkan, son of Party of Regions MP Volodymyr Demishkan, who was until recently head of the Vinnytsia Region Administration and is now president of Ukravtodor. According to the mass media, Serhiy Demishkan and his accomplices kidnapped Vasyl Kryvozub, CEO of an air transportation company, in 2007 and drowned him in the Dnieper. Nevertheless, when the blue-and-whites came to power, the suspect was released on recognisance not to leave.

One of the biggest concerns about Ukraine’s penitentiary system is, according to human rights advocates, that it is not working to prevent repeat crimes. As of today, 51.9 per cent of Ukrainian prisoners (about 56,100) are repeat offenders. In 2010, the situation further deteriorated when this index rose to 55 per cent. That the government does not care about rehabiliting criminals can be seen from the line in the 2011 National Budget which allocated a mere UAH 2.4 million to train prisoners in vocational institutions within penitentiaries as part of their social adaptation.

Human rights advocates also point to extremely alarming trends in the way penitentiaries are staffed and the low quality of their personnel. This is only logical: the turnover rate there is about 30 per cent, which is too much for a service that needs to have psychologically trained specialists with many years of experience.

Punitive measures are applied to the imprisoned who protest and complain. Donetsk Memorial has registered a significant level of corruption among prison personnel, “particularly in the application of parole.” Bribery detection has been on the rise, but it has had no effect on the overall level of corruption among prison guards.

WHAT TO DO?

It is evident today that Ukraine needs to reform its penitentiaries. Above all, regulations governing pre-trial investigation and keeping suspects in custody should be revised. Clear and binding criteria need to be set out to determine what preventive measure should be applied to what category of suspect. Moreover, electronic bracelets, microchips and other new technologies to track the location of suspects urgently need to be introduced. These novelties are contained in the new Criminal Procedure Code, but it would make more sense to amend the existing one rather than wait for a new edition. On the one hand, this will permit a saving of about a million hryvnias per day, and on the other, thousands of suspects would avoid coercion and torture. Finally, the state will then be able to meet the internationally recommended 4 sq m per suspect in penal institutions.

Another direction of reform is a drastically different approach to staffing penitentiaries. The selection and motivation of staff need to be changed. Instead of creating an army of 35-year-old pensioners (early retirement is the main incentive for those who go to work in the penitentiary system), it would be much more efficient to create a career path for the staff with a decent social package, salary, etc. Prisoners that are released need to be able to socialise. To this end, they should be given an opportunity to earn real money while in prison. If necessary, they should be able to learn a trade. (For example, in one women’s colony in Russia the inmates learn to code and return to life outside prison as software engineers.) Released prisoners should receive legal aid with issues like registration at a place of residence, court appeals regarding deprivation of property, etc.

Civic monitoring must be stepped up, because the experience of 2005-2009 proved that specialised human rights organisations are highly efficient in reducing the scope of torture and killings in prison. At the moment, the situation is the exact opposite, and some bureaucrats are abusing the penitentiary “reform”. The Audit Chamber found that UAH 130 million was used inefficiently in 2006-2010 under the State Program to Improve the Conditions of the Imprisoned and Detained. The Donetsk Memorial NGO says that only eight of the 23 recommendations brought to the attention of government bodies in 2011 regarding the operation of penitentiaries are being acted upon to some degree. Regulations, both ministerial and national, are essentially stalled. The rights of convicts continue to be violated both on the level of overall conditions in which they are kept and in the way the staff treats them.

CRIMINAL TRENDS

– The prison population has grown over the last three years and has reached the mark of 345 prisoners per 100,000 population

– The number of life-sentence prisoners is also on the rise and was at 1,727 (including 20 women) on 1 July 2011

– Detainment as a preventive measure is applied on an unjustifiably large scale

– The number of tuberculosis sufferers is gradually declining in penitentiaries, but the number of HIV positive inmates is steadily growing

– The mortality rate in the first six months of 2011 grew by 46 per cent and the suicide rate by more than 20 per cent