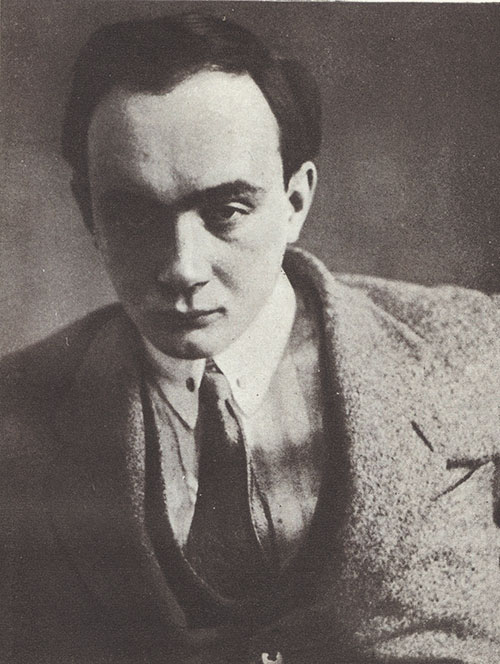

Of all Ukrainian writers of the Soviet era, Mykola Bazhan was nearly most kindly treated by authorities. In January 1939, he was awarded the Order of Lenin. As legend goes, Stalin personally added Bazhan to the list of laureates when he heard about his first Ukrainian translation of Shota Rustaveli’s poem The Knight in the Panther’s Skin. In 1940 he joined the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine (CPbU), from 1952 until his death he was a member of the CPU’s Central Committee. After the war and until his death he was consistently elected a deputy of the Verkhovna Rada (Supreme Soviet) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the UkrSSR. From 1943 until September 1949 he was Deputy Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the UkrSSR (in 1946 the government was renamed the Rada Ministrov (Council of Ministers) of the UkrSSR. In 1951 he was elected academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. To the first order of Lenin five more of them were added. He was also twice laureate of Stalin Prize, a laureate of Lenin Prize and of Shevchenko Prize, and also Hero of Socialist Labor.

In the Soviet hierarchy, Bazhan reached the highest peaks. When he was Deputy Chairman of Ukrainian government, Minister of Education Pavlo Tychyna and Minister for Foreign Affairs of the UkrSSR Oleksandr Korniychuk were subordinated to him.

It did not take long to enroll Bazhan in the classics and his literary works to be learnt at school. So Soviet theorists of literature took great pains to deal with his far from being perfect biography: to start with his father – follower of Petliura (Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army – Ed.), sotnik of the Army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, to follow with his executed fellow-writers and to crown it all with his half-German wife whose relatives stayed in the occupied territory and registered as “Volksdeutcshe” (ethnic Germans). Some of these facts were concealed, some were kept out of the public eye, and some were given publicity but rarely and reluctantly.

RELATED ARTICLE: An artist against the machine

What else do we not know about Bazhan on the threshold of his 115th anniversary? About him, not about his relatives, his parents, for who, according to Comrade Stalin, “djeti nje atvjechajut”(“Children are not responsible”) And why for a long time were they not willing to talk about?

Bazhan-designer

In the futuristic past of Mykola Bazhan, and so much undesired, there was another role of which no biography has mentioned. In 1923, Nick Bazhan made his debut as a poet-futurist with the poem Surma Jurm(“Horn of Crowds”), and simultaneously as a designer and typographer.

That year, the private futuristic publishing house Golfstrom published a beautiful red Zhovtnevy zbirnyk panfuturystiv (“October Collection of Panfurtists”). Obviously, it was Pavlo Comendant, the legendary publisher and organizer, who raised the money – this was a lonely futuristic book, he had his hand in.

The collection shows that panfuturists already back at that time realised: design is above all. Who knows how fashionable typography was in the mid-1920s, but futurist poets Heo Shkurupiy and Nick Bazhan played with it. The cover (wrapper in their terminology) of the Zhovtnevy zbirnyk panfuturystiv (“October collection of panfuturists”) was performed by Nina Genke-Meller, the avant-garde artist, Vadim Meller’s wife. And the montage, as stated on the back of the title, was made by Heo Shkurupiy and Nick Bazhan. Montage there meant layout, design.

In the book – it is almost unbelievable! – there are no poems by Mykhail’ Semenko. For the Zhovtnevy zbirnyk panfuturystiv (“October collection of panfuturists”) he wrote only slogans. Shkurupiy and Bazhan, often changing and composing fonts, placed those slogans not only on separate pages, but also framed with them other authors’ texts. Altogether in the collection there were 16 slogans plus Marx’s “Workers of the world, unite!”

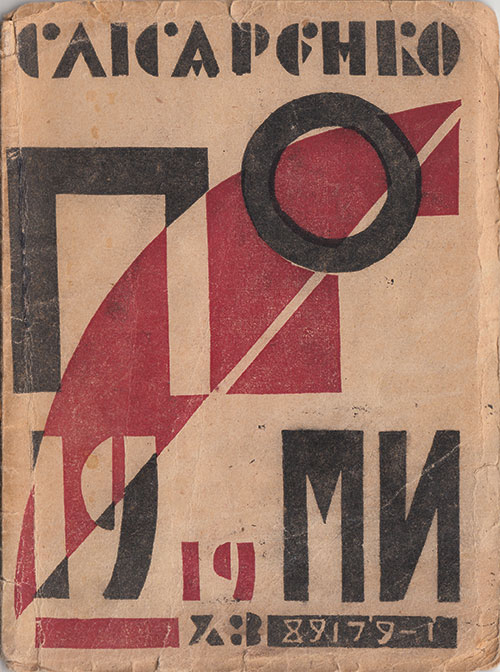

And also then in 1923 Bazhan – but that time without his new friend Shkurupiy – made a cover for the collection of futuristic poems by Oleksa Slisarenko Poemy (“Poems”). The constructivist cover was very unusual for its time: the geometrized red and black letters formed the word “Poems” and the number “1919”, obviously, the year. You had to look hard for the letter “Є” in the picture, although it is a lone red spot among black figures. Undoubtedly, in the common showcase, the collection attracted the attention with its bright (it is now it faded) and puzzling cover that was what the futurists sought for – to capture reader’s attention before he opened the book.

Another futurists’ edition of the same year – the collection of Geo Skurupiy Baraban (“Drum”) – is decorated with a font drawn cover in red and black colors, the author of which was not indicated. Probably, it could also be Nick Bazhan, because “Drum” and “Poems” by Slisarenko were decorated in the same color scheme and in a similar manner. Although it could be Shkurupiy himself.

His Soviet biographers preferred not to recall Bazhan’s artistic talents, because after that they had to explain to the readers who the panfuturists (Heo Shkurupiy and Oleksa Slisarenko in particular) were – too much new, or even forbidden, information; better to keep silent that the classic was also keen on drawing.

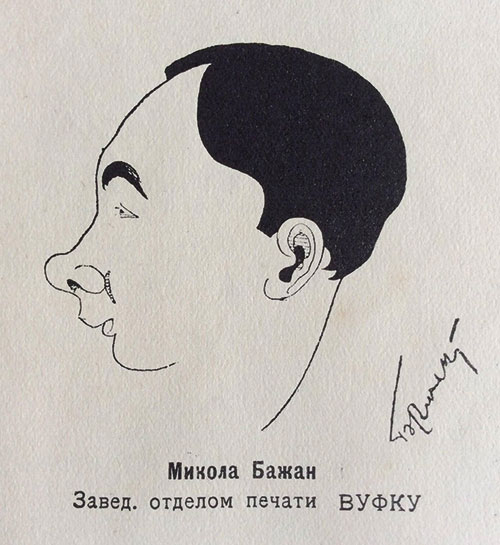

Bazhan-screenwriter

The leader of Ukrainian futurists Mikhail’ Semenko also brought Mykola Bazhan to the cinema. At first, Semenko went to Kharkiv to work in the All-Ukrainian Photocinematic Bureau and took Bazhan and Yuriy Yanovskiy with him as editors to the VUFKU (AUPCB – All-Ukrainian Photocinematic Bureau) script department. There was one step left to writing the screenplays, and Bazhan made it (as did Yanovskiy).

Cinema attracted writers with its novelty, opportunities, fame and fees, and in turn needed writers, because the laws of storytelling in the screenplay are the same as those of prose works. That is why in the mid-1920s, half of the screenwriters, half of the screenwriters were writers. And the record holder among them by the number of carried-out screenplays was Mykola Bazhan. Various directors made seven films using his scripts: Alim(1926), Mykola Dzherya(1927), Prygody Poltynnyka(“The Adventures of Half-Rouble”) (1929), Kvartaly peredmistya(“Uptown Blocks”) (1930), Pravo na zhinku(“Right to a Woman” (with Oleksiy Kapler; 1930), Rik narodzhennya 1917(“Year of Birth 1917”) (with Lazar Bodyk; 1931), Marsh Shakhtariv(“March of Miners”) (1932). Bazhan’s screenplays Mokra Prystan’(“Wet Pier”) (1932), Sertsya dvokh(“Hearts of Two”),Prystrast’(“Passion”) (both together with Yuriy Yanovskiy; 1933, 1934) and Kateryna(1937) remained ink on paper.

As we can see, Bazhan was both dealt with film adaptations of literary works and wrote his own original screenplays. Four of those films have survived, and we can still watch them today, but Bazhan probably never watched them, at least after WWII. Unfortunately, the most convenient for the Soviet regime, Mykola Dzherya – the film adaptation of Ivan Nechuy-Levitsky's social problem tale, which became ingrained in the canon of works of art on social justice and the struggle of serfs with their blood-sucking masters, has not survived.

Instead, the plots of Bazhan’s original screenplays one and all became of the taboo topics. Alimis the first film about Crimean Tatars, the script to which Bazhan wrote from the play by Ipchi Umer. The adventurous romantic-social film about the proud and courageous Crimean Tatar Robin Hood was very popular with the audience. In May 1944, the Crimean Tatars were deported. Even earlier, Ipchi Umer was repressed and exiled, and he died at Tomsk mental hospital. At first the film Alimwas edited, and in 1937 banned from showing, and its copies were destroyed.

It is enough to say about Prygody poltynnyka (“The Adventures of the Half-Rouble”) that its script Bazhan wrote on two stories about the children by the odious Volodymyr Vynnychenko (famous Ukrainian statesman, political activist, writer, and 1stPrime Minister of Ukraine – Ed.). It is not even clear how it was shot and released on screens, given the cooling in relations between Vinnychenko and the Government of the UkrSSR.

The film Kvartaly Peredmistya(“Uptown Blocks”) is about a Jewish girl, Dora, who fell in love with a Ukrainian youth, a worker Vasyl, and faced misunderstanding and rejection from both her own parents and Vasyl’s. That film written by Bazhan director Hryhori Hrycher-Cherycover shot in Bazhan’s native Uman. Later, in an essay about actress Nata Vachnadze, who played the leading role, Bazhan mentioned: “When I myself started working as a film editor and screenwriter, in the late twenties, I wrote the script of Kvartaly Peredmistya(“Uptown Blocks”), which told a story of the impoverished town of my childhood, a poor Ukrainian-Jewish town, where old, dark traditions of alienation, prejudice and prejudice still existed.”

In the 1920s, the Jewish theme was not uncommon in Ukrainian and, in general, Soviet cinema. However, on the example of shtetl life, it was difficult to show the class struggle and victory of the proletariat, so it was Sholem Aleichem whose screen adaptations were mostly filmed. The Kvartaly Peredmistya (“Uptown Blocks”) attracted with the story of modern life, and moreover, the film raised the question of women’s rights: it is one of the first Soviet films where the main character is a woman. It seemed like nothing seditious, but after the Holocaust’s non-recognition in the USSR, after prosecution of cosmopolitans and the “item 5” (a column in the Soviet passport for indicating citizen’s nationality, usually to detect Jews – Ed.) the picture about the struggle of a Jewish girl against “religious and low-browed prejudices” lost its relevance.

RELATED ARTICLE: Hollywood on the Black Sea coast

Another story of a young woman who breaks patriarchal stereotypes is the film Pravo na zhinku(“The Right to Woman”) (1930), a script to which Bazhan wrote with Oleksiy Kapler. Among Ukrainian panfuturists, Kapler was simply called Lucy; at that time no one could fancy what kind of adventures awaited him. Svetlana Stalin, a 16-year-old leader’s daughter, fell in love with nearly forty-year-old Kapler, winner of the Stalin Prize for the film about Lenin, and Kapler reciprocated her feelings. He paid heavy price for that short novel: he was soon arrested, condemned for anti-Soviet agitation (it was 1943) and sent to labor camps. Kapler was released and rehabilitated only after Stalin’s death. The fate of movie was also unlucky: Pravo na zhinkufor the first time since its premiere and release in 1930 was shown in 2015, nowadays.

Bush (the most) senior

In the 1920s, only one Bush was known in Kyiv, and it wasn’t George. That was how the film critic, editor of the magazine Kino (“Cinema”), editor of the Kyiv Film Factory Mykola Bazhan signed. Under that made-up name he also published one of his two cinematic books – Nayvazhlyvishe z mystetstv (“The Most Important of the Arts”) (1930).

In general, this side of Bazhan’s activity was not hidden by official biographers. In any reference-book of Writers’ Guild, any encyclopedia in the article about Bazhan you will find a terse line “In the 1920s he edited magazine Kino. In fact, those few words mean so much. Bazhan was the head of magazine Kinofor five of its best years, although the name of the editor was never mentioned in the magazine. He came to the editorial office in 1926, when founded a year ago magazine moved from Kharkiv to Kyiv, where a new film factory was being built inspiring young cinematic hopes in the city. Bazhan commissioned the design of the magazine to his long-time, as early as from gymnasium, friend Yuriy Kryvdin. Their parents served together in the Stavropol Regiment – Lieutenant Colonel Bazhan and Colonel Kryvdin, and then together in the army of the UPR. After Mykola’s hobby, Yuriy fell for cinematography: he made decorations and photo compilations for the magazine, published the book Shcho take kino (“What the Cinema is”) (1930), headed the publishing house “Ukrteakinovydav” (Ukrainian theater-cinema publishing house), in the creation of which Bazhan invested a lot of time and effort.

Bazhan attracted the best writing forces to collaborate in the magazine and later at the film factory and in Ukrainfilm, which emerged after the elimination of the VUFKU. It came to a point that the informants of the DPU (State Political Agency) reported that during hard times Bazhan employed all the literary friends at the film factory and ordered them fictitious screenplays only to support them financially.

In the early 1930s, writer Volodymyr Yaroshenko sarcastically called Bazhan “the evil genius of Ukrainian cinema”. He explained: “Whatever Bazhan may do for Ukrainian cinema, whatever he may recommend to do, cinema won’t benefit from it, but on the contrary, this will be harmful”. According to a secret informant, “Yaroshenko meant the following facts: editing for 5 years of the magazine Kino, that narrow-known body of VUFKU, a magazine which, without assuming self-criticism, incorrectly covered the state of filmmaking, did not engage worker correspondents, did not educate proletarian cinema-journalists; separated itself from the film community, focusing only on the narrow circle of petty-bourgeois intellectuals (Kosynka, Zhihalko, Atamanyuk, Frenkel, etc.)” This is a 1932 report, so it is enough to replace minuses with pluses – and we will have a more or less real picture.

Today, the refusal to involve working correspondents and take up the education of film journalists from regular socialist overachieving workers, called to literature, positively characterizes the magazine editor. And who did secret informant call among the “petty bourgeois intelligentsia (intellectual society)”? First-rate writers who should be looked up to by those who seek answers to questions. However, the informant said otherwise: “It’s not surprising that, when Bazhan left the editorial board (late 1930), the tone of the magazine got a little refreshed”. In fact, under Bazhan, Kinowas “the best two-weekly cinema magazine in the USSR” as it distinguished itself, and only that period of its history – vivid, meaningful, original – was first and foremost worth of descendants’ and researchers’ attention.

These and other undesired names and facts in Mykola Bazhan’s biography should not have been concealed. There were almost no friends, colleagues, and like-minded people when Bazhan became the deputy chairman of the Radnarkom (Council of People’s Commissars): most of them disappeared into the swirl of the Great Terror, and someone else died in the war. Heo Shkurupiy was arrested in December 1934 and executed three years later near Leningrad. Yuriy Kryvdin’s fate is unknown. Hryhori Hrycher-Cherycover made only two feature films in the 15 years since Kvartaly Peredmistya(“Uptown Blocks”). Therefore, those pages from the biography of the Stalin Laureate were not deleted – they were simply silent: maybe no one will be interested, everyone will forget. But you only pull a thread, as an entire iceberg will float to the surface, so there is a burning desire to call it a sort of a pun “Bazhan Undesired”.

Bio

Mykola Bazhan (1904–1983) was a prominent Soviet Ukrainian writer, poet, translator, and highly decorated political and public figure. From 1957 and until his death, Bazhan was the founding chief editor of the Main Edition of Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia publishing In 1970 Bazhan was nominated for a Nobel Prize in literature, but he was forced by Soviet authorities to write a letter refusing his candidature.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook