Since the Land Code was passed back in 2001, the idea has been to make land a commodity. Eleven years later, the issue of opening an agricultural land market is still contentious: should farmland be allowed for sale or not? If so, who should have the right to buy it and in what quantities? The government did not dare tackle the issue under President Leonid Kuchma or under President Viktor Yushchenko. Both supporters and opponents of the idea expected that the current government under President Viktor Yanukovych would try to put the problem to rest. The thinking was that it would surely be able to find a scheme under which Ukrainian chernozem (“black earth”, the soil contains a high percentage of humus and is therefore highly fertile – Ed.) agricultural land would be quickly appropriated by several families. However, on the initiative of Hryhoriy Kaletnik, Party of Regions MP and current chief of the parliamentary Committee for Agricultural Policy and Land Relations, the Verkhovna Rada prolonged the ban once again in late November 2012. This time, though, the moratorium was extended for another three years rather than one as before. The duration of the extension, which will expire on 1 January 2016, leaves no doubts that this was a political decision – the next presidential election is set to take place in 2015.

Some people with knowledge of the situation view the decision as coming from influential groups that aim to hinder the Family from adding agricultural land to the other attractive Ukrainian assets it has acquired. On the other hand, the Family’s business may not yet have accumulated enough financial power to do so. Another possibility is that it may be hoping to enjoy much more freedom of action, including less interference from influential oligarchs, after the problem of 2015 is resolved this way or another and the Family has concentrated all the power in its hands. It is clear that after the final redistribution of Ukraine’s assets, chernozem will be the only remaining resource with the potential of bringing in unheard-of profits in the future—provided, of course, that the right scheme is utilized. It appears that the potential Ukrainian land barons have yet to come up with one.

In any case, land remains one of the hottest issues in Ukraine and could trigger major confrontations both within the current government and between the government and the opposition parties as well as market participants, while prompting unpredictable reactions from millions of land-owning farmers. Add to this the historical Ukrainian attachment to land, which is viewed as a key factor of national security and sovereignty. Given all these nuances and circumstances, a decision may have been made (especially after it became clear that the Party of Regions would have no stable majority in the newly elected Verkhovna Rada) to remove this additional destabilizing factor.

NO SUPPORT?

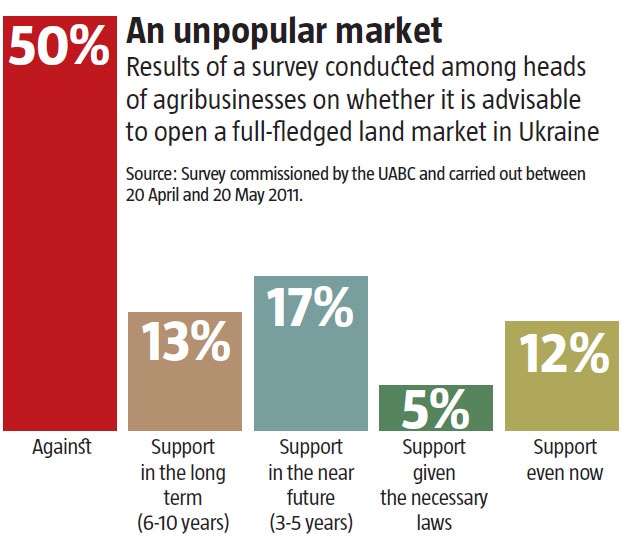

A survey of agricultural producers carried out by the Ukrainian Agrarian Business Club (UABC) in spring 2011 showed that 80% would support an extension of the agricultural land sale ban. Half of the respondents were categorically against, arguing that agricultural land should never be made available for sale and purchase. 17% were in favour but only for a moderate term (3-5 years), while another 13% favoured a long term extension (6-10 years). There were agricultural market players among the respondents: farmers, CEOs and owners of agribusinesses that arose from defunct collective farms, and top managers of agricultural holdings. This paradoxical fact has a perfectly logical explanation.

Modern economics states that what matters in a market economy is not who owns assets but who manages them. In Western Europe, farmers are in no hurry to purchase lands that multiple generations of their ancestors rented from descendants of local feudal lords. Ukrainian agribusinesses have a similar mindset as they rent thousands and tens of thousands of hectares from land owners. “The majority of companies working the land are not going to purchase it,” Harmelia Vice President Vadym Bodaiev says. And this is an optimal decision. For example, a company would need to fork out up to $50 million US dollars to buy 50,000 hectares of land. This is much more than the cost of the machines it uses to cultivate this area. Even agricultural holdings – not to mention less powerful companies and privately-owned farms – cannot afford to take this much money out of circulation, money they need now to upgrade their equipment and farms and purchase foreign-produced high-yield seeds, fertilizers, etc.

What agricultural investors badly need, Bodaiev says, is long-term stability in land relations, at least as long as their project’s payback period, which is 7-20 years in Ukraine. Moreover, Ukraine still lacks an adequate legal framework for transactions involving agricultural land, while they are strictly regulated in developed market economies. Not just anybody can purchase a plot of land there and not everyone has the right, even after purchase, to sow the field or use it as pasture for cattle. Most countries limit the range of potential buyers of agricultural land and quite a few restrict ownership to one person. Many more countries define who has the right to conduct farming.

Ivan Tomych, President of the Union of Agricultural Servicing Cooperative Societies, says that to put Ukrainian villages on the market track, the government needs to have a package of laws passed that would secure enough support for agricultural producers, reform local budgets and revamp the authority of local government bodies. In order for the land market to start operating, countless additional pieces of subordinate legislation and amendments to other documents are needed. For example, the Law “On the Land Market” was passed in the first reading and has been gathering dust in parliament for a year now because no one wanted to approach such a sensitive subject prior to the election.

A large portion of the land owners are also clearly scared by the prospect of land changing hands. They have good reason to be concerned about what might happen to their land in this environment of total legal nihilism, rampant corporate takeovers and authorities and businessmen that employ no-holds-barred tactics. What if skinheads start making rounds in villages, demanding that locals sell their land for next to nothing? A court that today strips citizens of their right to vote by annulling their ballots on contrived grounds may one day take away their private property as well, despite ownership rights being enshrined in the Constitution. Even if the judicial system were fair, an ordinary land owner would clearly be at a disadvantage in terms of the ability to defend his legal rights due to a lack of funds for court proceedings and attorneys.

WHO WILL BUY?

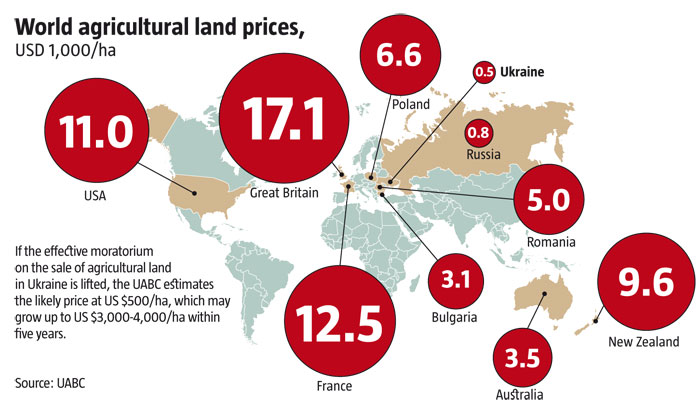

Ukrainian land is greatly undervalued. Experts say that if agricultural land had gone on sale starting on 1 January 2013, a hectare of chernozem would cost USD 1,000 on average, much less than $12,500 in France, USD 6,600 in Poland and USD 3,100 in Bulgaria, according to the UABC. The low price of Ukrainian land may attract profiteers and oligarchs.

Non-oligarchic capital is not being invested in Ukrainian agricultural land, but the moratorium is not the only obstacle. Another hindrance is Ukraine’s low business attractiveness. “Investors are very frightened and reluctant to invest in Ukraine’s agriculture,” UABC President Aleks Lissitsa says. This is also true of Ukrainian investors. On the one hand, large Ukrainian agribusinesses report multimillion-dollar investments. On the other hand, the majority of these go to relatively liquid assets that can even be taken abroad if need be, while investments in fixed property or infrastructure are in the range of hundreds of thousands of dollars, rarely millions, even in the case of fairly successful agricultural holdings that use 10,000-20,000 hectares of land. In order to buy land the company cultivates, it will need at least USD 10mn, even if prices remain as low as they are now. Investing this much money in fixed property, which essentially means burying it, is something large businesses are not ready to do because no one can say precisely how quickly investments will be recouped. In fact, this is the reason why, with few exceptions, Ukrainian oligarchs, who are accustomed to reaping high profits, have not hurried to target Ukrainian agricultural land. However, there are people who are willing to get a piece of the Ukrainian land pie even now without any reservations. These are, above all, investors from the Persian Gulf area and China. First, they are used to doing business according to informal agreements rather than law. Moreover, they have more experience working in countries that, like contemporary Ukraine, have low legal and business cultures. For example, they are actively buying land in Africa. Second, we are talking about government companies in China and relatives of local monarchs from the Persian Gulf countries. Both have close ties to the state and hence more leverage with the governments of the countries they operate in. But the main thing is that they are after more than just making a profit – their strategic goal is to provide a stable source of food for their countries amid increasing global food and water shortages and thus to insulate themselves from possible revolutions. Oil sheikhs and Chinese government companies are not afraid to invest with an eye to the more distant future.

The consequences of Arab or Chinese investments in agriculture are viewed by many as a threat to economic security, especially in undeveloped countries. For example, in Russia agricultural holdings controlled by the Chinese (those who have managed to acquire Russian citizenship or non-residents acting through proxies) are rapidly turning into veritable Chinese colonies. They hire as many Chinese labourers (often illegal) as possible, while their farms switch completely to Chinese seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. One consequence is growing imports from China. Another, more alarming consequence is that Chinese seeds may be genetically modified (the country sets no limits on GM foods), while Chinese pesticides are extremely toxic. For example, DDT is still being applied there, and Chinese versions of the pesticide can still be found in products six months after harvest, while original pesticides made by leading Western producers completely decompose within two to four weeks. GM plants may cross-pollinate standard plants within the range of two kilometres, while pesticides contaminate ground water and rivers. Of course, developed countries have controlling bodies that do a fairly good job of preventing this kind of un-green behaviour, but the situation is completely different in countries where any issue can be solved with bribes. Moreover, China sometimes presses for the right to apply its own technological standards. For example, this is its intention for the Chinese-Belarusian industrial park near Minsk. As a result, the use of GM foods and harmful pesticides becomes completely legal in these areas, while Chinese investors turn out to be above the law in the country of operation.

However, the Yanukovych regime seems to be turning a blind eye to these and many other existing threats to national security. China has already opened a USD 3bn credit line to develop joint agricultural projects, half of which are aimed at improving irrigation systems in Kherson Oblast, a region of fertile chernozem land and one of Ukraine’s most sparsely populated areas. Considering the Chinese experience of investing in African countries, it may be assumed that China invests this much money in upgrading agricultural infrastructure with an eye to putting it under its complete control later.

Amid tense relations with both the West and Russia, the current Ukrainian government is increasingly seeking support in the Far East. This is not surprising because China differs from other world leaders in being completely indifferent to the ideological inclinations of its partner countries. The only condition is that they boost its economic power in the world arena.