As the capital of Ukraine, Kyiv has its own open air museum – the National Museum of Folk Architecture and Life of Ukraine, generally known as Pyrohovo. It has been around for over three decades, having opened its doors in 1976. Sprawling across 133.5 hectares of land, this is the largest museum of its kind in Ukraine. Despite its impressive size, Kyiv residents and visitors are well-acquainted with it and have seen most of its buildings, which, by the way, are not in the best of shape now. So it makes perfect business sense to invest in similar new skansens: peoples’ interest in them, particularly during folk festivals leaves no room for doubt. For example, Mamajeva Sloboda, located in a park next to the National Aviation University and near the city centre, has been a great success since its opening in July 2009. The place is packed during festivities. Visitors can spend time in the recreated living quarters of regular and senior Cossacks, attend a Liturgy at a wooden church, built in line with the canons of ancient Ukrainian architecture, get a bite to eat in a real tavern and learn interesting crafts during master classes. The museum’s main drawback is its location. It is surrounded by the city, so it is sometimes hard to ignore the clumsy multistoried buildings towering over a cosy recreated village house or threshing barn. To help Kyiv residents, who are generally reluctant to spend their vacations on an ethnographic expedition, a brand new museum complex, the Ukrainian Village, was built near the village of Buzova in the Kyiv-Sviatoshyno District.

THE LIFE OF ANCESTORS

The museum itself is divided into six mini-zones, representing different regions of Ukraine. Each features authentic houses (some over 180 years old) which were transported from these regions and painstakingly put together by specialists who were advised by ethnographers. Not only the houses and their full decorations but also numerous outbuildings have been reconstructed – threshing barns, potteries and blacksmith’s shops. The Sloboda Ukraine zone even features a miniature operating distillery and conducts master classes in the making of moonshine. Nearly all the structures at the open air museum are functional, so they are not in danger of going to rack and ruin.

There is a house on either side of the entrance to the Ukrainian Village: one dated 1888 from the village of Pyshnenky (representing the region of Ukraine along the middle reaches of the Dnipro River) on the left and a Hutsul house from the Carpathians on the right.

The former has an interesting oven that is characteristic of the Poltava region. In the larder of the latter, there is an unusual bed which appears to bulge up in the middle. According to tour guides, it is supposed to create some privacy for the husband and wife, because sex life was virtually impossible in houses which traditionally also accommodated many children. An important detail: there is a playground (the smaller one of the two there) near the Hutsul house, so children are sure to have fun.

Located on the museum’s territory is the Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki Church, which is always open. Its iconostasis, carved by contemporary specialists, is almost comparable to ancient models of Ukrainian Baroque. The church’s policy is to attract rather than repel people, so no critical remarks are made regarding visitors’ external appearance.

There are four more homesteads on the neighbouring, larger part of the Ukrainian Village. These represent Sloboda Ukraine, Southern Ukraine, Polissia and Podillia. Curiously, the house from Podillia has painted images both outside and inside, all made by professional artist Oksana Horodynska. She made the oven especially vivid by covering it with classical images of roosters, guelder-rose, oak leaves and numerous flowers.

Visitors who come to the museum on Saturdays can buy freshly baked bread and participate in the baking process. This is just one of eleven master classes conducted by the museum. In addition to baking, instruction in offered in Petrykivka painting, pottery, smithing, Easter egg painting and even chopping wood. There is also a small zoo. Just don’t expect to see any exotic animals there – the zoo only has traditional Ukrainian domesticated animals: piglets, rabbits, sheep and guinea fowl. Nevertheless, this does not take away from the joy of interacting with them, especially for children.

EXPLORING ETHNIC VARIETY

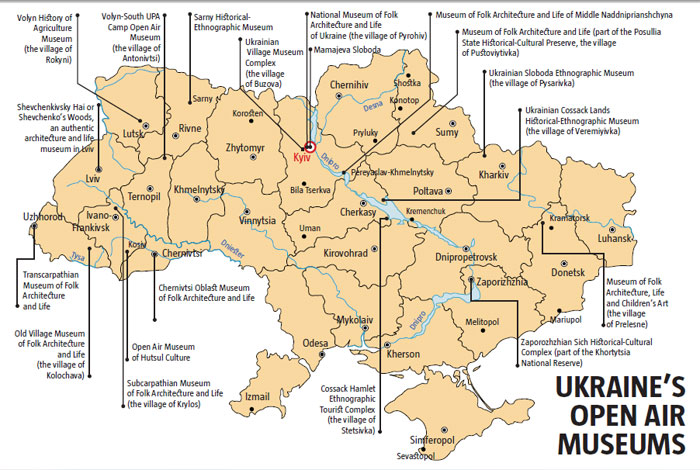

Compared to other post-Soviet countries and even its Western neighbours, Ukraine has quite a few open air folk museums. Most of them are located in Western Ukraine, and just two are to the East of the Dnipro River. One is the diminutive Museum of Folk Architecture, Life and Children’s Art in the village of Prelesne, Donetsk Oblast, which consists of just one village homestead typical of Sloboda Ukraine. In contrast, the other – the Middle Naddniprianshchyna Museum of Folk Architecture and Everyday Living located in Pereyaslav-Khmelnytsky, is vast. It is big enough to keep visitors on their feet for an entire day or even longer. One of the museum’s biggest draws is its wooden churches. Taras Shevchenko once painted its Saint George’s Church. Another, Saint Paraskevi of Iconium, is home to – surprise! surprise! – the Space Exploration Museum with a Foucault pendulum in the middle.

Understandably, museum specialists have paid particular attention to the Carpathians with their living authenticity. Three other open air museums focus on the life of the highlanders. An exception is the Chernivtsi Museum of Folk Architecture and Life, which generally focuses on the lifestyle of people living in the lowlands of Bukovyna. This museum has a rich tradition of carnivals, particularly the Epiphany, for which participants come from a number of villages in the region. The lifestyle of the Hutsuls and their neighbours, the Boikos, from either side of the Carpathians, is represented in two open-air museums: one in the village of Krylos near Halych and the other in Uzhhorod. Both are quite compact, but the latter is perhaps the most photogenic, since it is located in a picturesque area under the walls of an ancient castle.

The old-timer among Ukrainian skansens is the Museum of Folk Architecture and Life in Lviv, known as the Shevchenko Orchard. It received its first exhibit, the Saint Nicholas Church from the village of Kryvka, back in 1930 thanks to the efforts of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky. The museum continues to make acquisitions and is now waiting for one of the few surviving wooden Roman Catholic churches from the village of Yazlivchyk, near Brody. The Shevchenko Orchard quite successfully competes with Kyiv’s Pyrohovo in terms of the number of events it hosts and has the major advantage of being centrally located. It is within walking distance of Lychakivska Street and the Lviv High Castle (Vysokiy Zamok).