“A large current-account gap implies lots of net borrowing from abroad, which could presage a credit crunch if funding dries up. A high level of short-term external debt relative to a government’s stock of reserves means an economy lacks the means to tide borrowers through temporary difficulties. Rapid credit growth often signals overstretched firms and overvalued asset prices. A more open financial system may boost growth in the long run, but it also makes it easy for capital to flood out fast,” the publication writes.

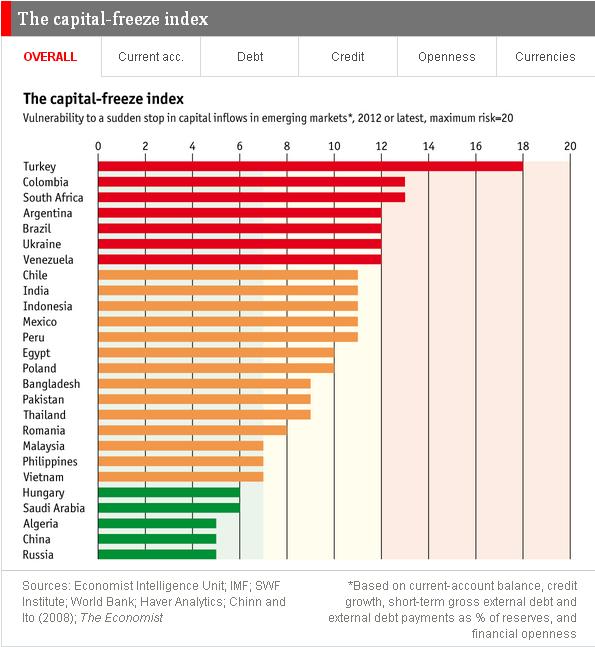

The Economist combined these four factors into an index measuring the vulnerability of 26 emerging markets to a capital freeze. “We have used a simple traffic-light system to group the countries. Green denotes economies, including reserve-rich oil states, that are at relatively little risk from a sudden stop. A current-account surplus, a vast hoard of reserves and a closed capital account mean that whatever troubles befall China, they are unlikely to include a panicked flight of capital,” The Economist notes.

“Countries in the red zone are most at risk. South Africa, Ukraine and a clutch of Latin American countries all look vulnerable, but Turkey tops the list,” the article concludes.