Ninety years ago, one of the most notorious assassinations involving Ukrainians took place. In broad daylight, on an ordinary workday, right in the heart of Warsaw, a Ukrainian militant shot Poland’s Minister of Internal Affairs and promptly fled the scene.

Peratsky: “The hero of the Lviv’s streets”

The future Minister of Internal Affairs of Poland, Bronisław Pieracki, first gained recognition during the Ukrainian-Polish War of 1918-1919. Before World War I, both nations were deprived of statehood and divided among empires. In 1863, Bronisław’s grandfather took part in the uprising against the Russians and, after its defeat, moved to Austria-Hungary. Born in 1892, Bronisław joined the scouts (known as Plastuny in Ukrainian) during his gymnasium years. During World War I, he volunteered for the Polish Legions, similar to the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen. His path closely mirrored that of his Ukrainian peers.

At the end of the war, he found himself in Lviv, right in the midst of the Ukrainian-Polish struggle to secure a national state. The Poles won, and the 23-year-old Pieracki was promoted to major and awarded the Virtuti Militari for bravery.

Photo: A group of Polish legionnaires (volunteers). The second from the left is 20-year-old Bronisław Pieracki, in 1915.

His Ukrainian peers showed no less fervour. Dmytro Paliy, one year younger than Peratsky, was one of the organisers of the November Uprising, which proclaimed the Ukrainian state in the Western Ukrainian territories.

Reflecting on the night of 1 November 1918, he wrote, “Each of us saw that we must start today or never. But by choosing the latter, could we then call ourselves a nation?”

Meanwhile, Yevhen Konovalets, four years older than Peratsky, formed one of the most battle-ready units of the Army of the Ukrainian People’s Republic in the Trans-Dnipro region—the Sich Riflemen.

Although the Ukrainians suffered a devastating defeat, they swiftly moved to create an underground resistance movement—the Ukrainian Military Organisation. The emergence of this underground movement was hardly surprising: the Poles had captured Galicia, but the post-war borders were still being determined by the Entente powers, and there was no consensus on the state affiliation of these lands. Yet, in March 1923, Galicia was officially recognised as part of Poland. During that time, the Ukrainian underground movement repeatedly made its presence felt, even attempting to assassinate Piłsudski in Lviv. As a result, Paliy ended up in prison, while Konovalets went into exile.

Bronislaw Peratsky’s biography was calmer—he served in the Ministry of War. His brother, Stanislav Sheptytsky, who was Metropolitan Sheptytsky’s minister, described him as “a very good head of the department of non-Catholic rites, who excellently navigated and managed them with great talent in those complex matters.”

Legal path vs revolutionary underground

The international recognition of Galicia as part of Poland had a profound impact on Ukrainians. In 1925, their underground institution—the Secret University, where thousands of students studied—was closed. That same year, the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance, the most powerful political force, was founded. It seemed that legal avenues were taking precedence over underground activities. In the 1928 elections, several founders of the Ukrainian Military Organisation, including Dmytro Paliy, won seats as representatives of political parties. Bronisław Pieracki, representing the Non-Party Bloc, a political force that had emerged around Piłsudski, also entered parliament.

Pieracki’s career was a blend of military service, involvement in Masonic lodges, and participation in underground organizations. In May 1926, when Piłsudski organized a state coup, Pieracki supported the railway workers’ strike, effectively halting the advance of pro-government troops toward the capital. Among Piłsudski’s close circle of colonels, Pieracki stood out as the youngest and the only one who had not fought in the 1st Brigade under Piłsudski’s command.

While Ukrainians refused to accept the loss of statehood, it appeared that political means could resolve all the contentious issues, even bringing former combatants who fought on the streets of Lviv, like Pieracki and Paliy, together under the dome of the Sejm. However, Bronisław received a new assignment—he became the deputy minister of internal affairs.

Photo: Yevhen Konovalets (first on the right) among combatants upon returning to Galicia, Vorokhta, 1921. It was within the ranks of former military personnel that the revolutionary Ukrainian underground took root.

During this period, Ukrainian-Polish relations swiftly deteriorated, particularly when it came to education. The issue stemmed back to Piłsudski’s predecessors, the national democrats, who introduced utraquist, or bilingual schools. Although Piłsudski’s associates publically condemned such actions, citing the harsh Russification policies before the war, the laws remained unchanged and eventually became even stricter—schoolchildren were mandated to celebrate Polish state holidays, including Marshal Piłsudski’s name day.

Hence, it’s no surprise that underground movements began to surface in Ukrainian gymnasiums. Unlike their older counterparts involved in liberation struggles, Ukrainian youth tended to be more radical.

They faced constant pressure from school administrations, showed enthusiasm for the Ukrainian Military Organisation, and established their own organizational structure. Their representatives actively participated in the founding assembly of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) in February 1929.

The merging of several nationalist groups did not necessarily lead to the creation of a revolutionary organisation. The OUN united a range of political figures, with a majority of delegates at the OUN Congress hailing from the Trans-Dnipro region. Yet, in Galicia, it was the youth who spearheaded the newly formed organisation, namely the leaders of the Union of Ukrainian Nationalist Youth. The rationale behind this was straightforward – the older generation was a bit wary of the new setup.

“Baba”, the head of the OUN’s ‘krayovyky’ – the regional leaders

The underground was experiencing a crisis, and in May 1930, Konovalets wrote: “I ring the bell to kick-start the OUN’s work from a dead point.” The regional youth sparked the movement, organizing a massive sabotage campaign in the summer of 1930. But Poland faced greater challenges, and Piłsudski decided to dissolve parliament and imprison opposition deputies.

For Poles, there was another way to suppress Ukrainians, and it was exactly how they named it – “pacification.” Instructions for its implementation in Lviv were conducted by the deputy minister, 35-year-old Bronisław Pieracki. About a thousand villages were ‘pacified’, and the matter was even debated in the “League of Nations.”

Piłsudski was satisfied with this display of a political force, and Pieracki awaited his promotion – the position of deputy prime minister. In May 1931, he became the minister of internal affairs and remained so despite changes in the cabinet. It was an interesting time when yesterday’s revolutionaries took turns leading the government: Piłsudski, Pristor, and Slavik. Before the war, they battled against the Russian Empire, hastening the arrival of Polish statehood.

Photo: The government of Leon Kozłowski, May 1934. Minister Pieracki sits on the far left – one of the key figures in the government.

Overall, the situation with Ukrainians seemed to be contained—the revolutionaries were making their presence felt, but within the region known as ‘Eastern Lesser Poland’ (formerly Galicia), the Polish state authorities took cautious measures. Since 1924, following an assassination attempt on President Wojciechowski, they have even refrained from visiting Lviv.

Galicia was often likened to the “Ireland beyond the San River,” and tensions were palpable. ‘Krayovyky’, the regional leaders of the OUN, were systematically targeted by the police: some were gunned down during “investigative experiments” or were brutally interrogated and died shortly after release from prison, while several others received lengthy prison sentences.

In the fourth year of the OUN’s existence, the leadership transitioned to 24-year-old student Stepan Bandera. Affectionately dubbed “Baba” by his mates, Bandera was the youngest among the leaders but distinguished himself with his unwavering resolve. In 1933, he orchestrated an assassination attempt on a Soviet diplomat as a protest against the Holodomor. Another significant event occurred when Bandera ordered a militant to surrender to the police to testify in court about Bolshevik crimes. This may have been the first recorded instance of a militant being sentenced after surrendering.

The Warsaw assassination

During organisational meetings, Bandera often found himself at odds with Konovalets – disagreements between regional leaders and those in exile were not uncommon. However, the overall direction of the organisation was largely influenced by the younger members. Konovalets once remarked, “It is challenging for those deeply entrenched in the emigrant mentality, accustomed to the civilised conditions of European states, to lead a revolutionary movement…” He further noted, “The burgeoning nationalist movement in the Western Lands does not welcome us. However, I am confident that as it consolidates and matures internally if we do not seek common ground, it will naturally develop its own leadership.”

Contrary to the prevailing trend, regional leaders began to assert themselves, prompting the leadership in exile to not only endorse but also instigate assassinations. One such plot was planned in Warsaw, with Minister Pieracki identified as a potential target. He was chosen partly because, surprisingly, he had relatively minimal security – rumour had it that the unmarried minister kept his personal life discreet.

Various sources had hinted at Ukrainians plotting an assassination attempt. Six months prior, a portion of the OUN archive, known as the “Senyk archive,” had fallen into police hands. Investigating judge Jerzy Luksenburg lamented, “Materials vital to the minister’s safety lay unexamined and untranslated within his own ministry.” Additionally, a German report warned of the impending attack. Yet, this report became lost within government offices and failed to reach the necessary authorities in time.

Photo: Funeral procession for the murder of Pieracki. Warsaw, June 1934.

Towards the end of May 1934, Mykola Lebed, the mastermind behind the assassination plot, attracted police attention. His suspicious activities were noted as he exited an OUN laboratory apartment in Krakow, carrying a bomb intended for the minister. Authorities planned to apprehend him at the Lviv train station, but Lebed unexpectedly boarded a train to Warsaw instead.

The police had compiled an extensive list of Ukrainian nationalists and were poised to make arrests. In Krakow and Lviv, this was scheduled for early June, but the minister embarked on a tour of Galicia, unwilling to disrupt society. Upon his return on June 14, 1934, mass arrests ensued. Nearly all the key regional leaders, from Bandera to the underground laboratory organisers, were detained. The following day, a militant fatally shot the minister (the bomb failed to detonate) and managed to evade capture, fleeing Warsaw.

“Colonel Bronisław Pieracki fulfilled his duties diligently and honourably, dying like a true soldier on June 15, 1934,” read Minister Piłsudski’s order to military units. Indeed, the Ukrainian-Polish conflict bore the unmistakable essence of warfare. The paradox lay in the fact that it was the youth on the Ukrainian side, graduates of Polish state schools influenced by polonisation, who became revolutionaries, challenging the Polish administration.

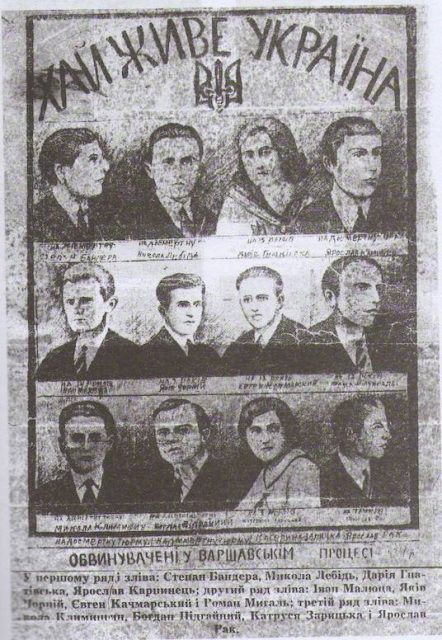

Photo: Postcard with the defendants in the trial for the murder of Pieracki. All defendants are aged between 21 and 31 years old.