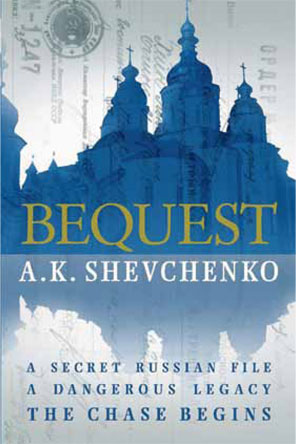

Our interview with Anna Shevchenko, a Ukrainian-born writer who now lives in Britain, took place at the European Books Festival of Cognac. Her debut thriller Bequest is about the British, Russian and Ukrainian intelligence services' hunt for Cossack Hetman Pavlo Polubotok's gold. The French translation of Bequest has turned out to be a big hit. Visitors kept interrupting the interview to get an autograph or ask Anna who the hetmans were and whether or not it is safe to travel around Ukraine in a camping trailer, and whether or not she remembers the day Chornobyl exploded. We also spoke with her about trends in British literature, the responsibility of writers for the image of their nation and Western stereotypes about Ukrainians.

UW: Are there many writers in the UK who write about anything linked to Ukraine?

I’d say that Ukraine mostly comes up in political journalism. A lot of research is published on Ukraine’s geopolitical choices. But these are not novels. An interesting book called Odessa Brides was recently published in English. It’s by Janet Skeslien Charles from New Zealand. Janet presents a great portrait of what was going on in Odesa between Perestroika and 1991 when Ukraine gained independence, giving an extremely interesting perspective of Ukrainian reality through a foreigner’s eyes. Apart from that, Andrey Kurkov’s, Maryna Levytska’s and my novels about modern Ukraine have been the only ones published in English, as far as I know.

UW: Is Bequest your first novel?

Yes, but I published two books with research on Ukrainian and Russian mentality earlier. This was where it all started. My first book was a brief guide on Ukraine from the perspective of Ukrainian mentality. It was published in 2005. I did this because it would get Ukraine into a series of books about different countries. The actual research cost me two-three times more than the paycheck was. What surprised me though was that I found absolutely nothing on Ukrainian mentality when I began to look for contemporary research. After the first two books were published, my grandmother gave me my grandfather’s diaries to read. He was a dissident and a professional historian. It was really painful to read his diaries. “Write a story about all this if you want to leave the memory of your grandfather,” my granny told me. “Make it a novel this time.” I was pregnant at that point — expecting a child and “expecting” a novel. It took me 12 years to research all the sources and complete the book.

UW: Tell us about your grandfather, Fedir Shevchenko…

He had a sad and difficult life, one typical of an intellectual in the 1970s. He was a historian and the director of the Archeology Institute. He wrote the truth about Ukrainian historian and first president Mykhailo Hrushevsky, but it was prohibited; did research on Ukrainian Cossacks and edited the Soviet Encyclopaedia. He was a versatile, talented man who was known in the world. That’s what the authorities didn’t like about him. Anonymous reports started coming in against him and his name was removed everywhere. That was in 1972. Then, literary critic and dissident Ivan Dziuba was arrested and poet and dissident Dmytro Pavluchko faced persecution. Worst of all, my grandfather could have said so much and he never did. That was my major inspiration. I wanted to finish his unfinished work. After Perestroika, he was invited to speak about Hrushevsky at the Academy of Sciences. So many people came that they couldn’t fit into the auditorium and they stood in the doorway. But the system had broken him and he could no longer speak the truth. That was my worst pain. My grandparents inspired the characters in Bequest and this novel is dedicated to them.

UW: Do you see yourself as a writer of high or popular literature? Do you accept the division?

I don’t think of myself as a writer. I’m just a story teller. I see things as if they were in a movie. I use different stories from Ukraine to bring its history to a mass audience. It’s not that I don’t respect highly intellectual literature. It’s certainly very important. I’m just not sure today that I can do it. By the way, I was inspired to start writing books by my neighbours' six-year old daughter. I used to take her to school with my daughter and she would give me three words and I had to make a story out of them every day. I had just 20 minutes to do that while driving the girls to school. And she would edit me all the time. Then six months later she told me, “Now you can really start thinking about writing books.”

UW: Still, you write historical detectives, not children’s books…

The key message of my first, second and maybe the two other books I’m currently contemplating is to show that history tends to take revenge. Subsequent generations get to pay the price for treating history carelessly. My next book is about the secrets of the Yalta Conference, the documents we don’t know about. I worked in the UK and American archives, Livadia palace in Crimea, and talked to many different people. And there were some secrets there. The information I will reveal in my book will disturb some people. But not knowing it is even more dangerous.

UW: Do you feel yourself a British or a Ukrainian writer?

For me, the plot, the shape and completeness of a story are the priorities. This is what you can reach in any language. The point is what you write about.

UW: Do you think festival promotion is effective for writers and the nations they represent?

The Cognac literature festival is very vibrant, lively. It attracts people who have nothing in common with a given country but want to know more about Ukrainian history and culture. The festival is not commercial and reveals new music, photos, literature and art… All generations come here. Some people have been to Ukraine to study or just travel, but most have only heard that the country exists. I think this festival is a great initiative.

UW: Are Ukrainian writers seen as something exotic in the West, or are they an integral element of the common European image?

Sadly, they’re definitely exotic. I’ve experienced this myself. Ukrainian literature is viewed as something new, an alien world. Recently, I did a programme on trips to Crimea, Russia and the Far East for the BBC. I was invited to talk about my second book on the Yalta Conference and I accepted the invitation only because I had a chance to tell something about Ukraine. Surprisingly, Ukraine was not mentioned once in the draft programme.

UW: How similar are the themes in contemporary Ukrainian and British literature?

I would probably combine this question with the theme of football, although it may surprise you. And I’m not talking about Euro 2012. There is a book called Dynamo: Defending The Honour Of Kiev by Andy Dougan. It’s about the Death Match of Kyiv Dynamo during World War II. A film with many British celebrities, including Gerard Butler, will be done on it soon. You may think that this has nothing to do with the problems Ukraine has now but the situation actually reflects British mentality. The British like to support the losing party. The concept of the losing party getting victory in the end makes Ukraine much more closer to the UK than any common economic or art events. That’s how bridges are built – through football and history. For me, that was an important example of how a story that had nothing to do with modern time engaged Ukraine into the current trends in the UK.

UW: What other trends are popular in the UK today? What Ukrainian writer could fit them?

Maryna and Serhiy Diachenko, definitely. Their fantasy is something the British find extremely interesting. Black detective stories also have a chance in the UK. Just look at all these popular Scandinavian novels. Kurkov fits in really well with his irony, sarcasm and surrealism that the Brits love and understand.

UW: Do your books build bridges? Do they contribute to creating the image of Ukraine in the West?

I think the Bequest contact has worked. Its detective element helped. And the plot – the hunt for gold is always interesting and everyone is familiar with it. I wanted to communicate Ukrainian history to the readers through this story. When a British newspaper wrote that “Shevchenko compiled a brief course on Ukrainian history,” I felt that they got my message right. That was my goal.

UW: So, you realize that people on the UK now partly see Ukraine through your eyes?

I’d really like them to see Ukraine through more eyes than just mine. But that’s what we have at this point. They see it through the eyes of Kurkov, Denysenko and other modern writers. And I’m grateful to the British audience for finding my eyes helpful.

UW: Do you think writing, literature and storytelling entails responsibility?

Definitely, yes. I feel 100% responsible for what I do. The responsibility is actually huge.

UW: How do people in the UK see Ukrainians? Do they know anything about Ukraine?

They know the three stereotypes: Chornobyl, Andriy Shevchenko and mines. Sadly, that’s all. In summer, a surge of negative media surfaced before Euro 2012. The media often write about Ukraine’s endless political problems. But the good thing is that people have finally realized that Ukraine is a separate state. Ten years ago, they would often not distinguish Ukraine from Russia.

UW: Do you think Europe is finding Ukraine more and more interesting despite all our troubles?

I think so. A lot of French people came up to me at this festival asking not just about books, but about Ukraine and its history. Their questions ranged from Cossacks to Chornobyl. The 120-seat hall, where the roundtable on Ukrainian history was hosted, was filled with the French, with all kinds of questions and comments coming from them. These intelligent people wanted to enrich their own culture.

UW: Have your books been translated into Ukrainian?

No, the novels haven’t been translated yet. My first book Bequest has been published in 12 countries so far. Perhaps it will appear in Ukraine next year. I would be delighted if my books could reach Ukrainian readers.