Forecasting risks that ensue from Russia’s possible actions in the Black and Azov seas is no longer something extremely difficult or unrealistic – the experience of 2014-2019 serves the purpose, as long as we do not give in to the information and political hysteria around.

Russia’s occupation of Crimea unearthed the long conserved geopolitical divide along the Sea of Azov, the Black and the Mediterranean seas. Tectonic shifts like this do not stop on their own.

The processes of 2020 will be the continuation of Russia’s strategy and tactics, using military, geographic and geopolitical opportunities created in Crimea in six years of occupation beyond the peninsula. In a nutshell, its military threat and imperial expansion will be projected beyond Ukraine to cover the whole of South-Eastern Europe, South Caucasus, Turkey, and the Syrian knot in the Middle East with further development in North Africa. Another element of this is creation of Moscow-controlled chaos wherever possible, primarily in the EU and NATO states, as well as the Balkans.

The problem of freedom of navigation in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait that broke out “unexpectedly” in April-May 2018 should be viewed in this context. 2019 has already shown some elements, attempts and sketches of the “Azov technique” for the expansion of sea occupation into the Black Sea.

The analysis of ungrounded halting of vessels heading to/from Mariupol and Berdiansk, Ukrainian ports in the Sea of Azov, during the last 18 months reveals some patterns and leads to interesting allusions.

With no effective response from the international community, Russia has grown more brazen in the Kerch Strait, now using navigation asymmetrically as part of its demands for negotiations on unrelated issues, such as resumption of water supply to the occupied Crimea.

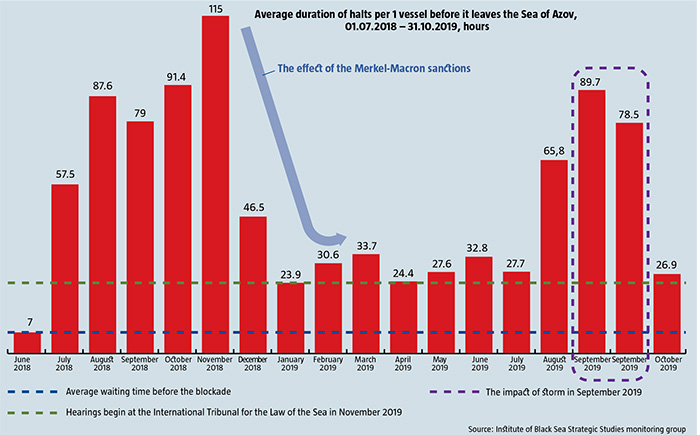

European leaders have used the same asymmetric approach to temporarily decrease the time for which ships are held in the Kerch Strait by linking this to the EU’s decision-making on the construction of Nord Stream 2 and direct sanctions against Russian ports in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. In Ukraine, this move was sometimes referred to as “the Merkel-Macron ratio”.

Once Nord Stream 2 received final approvals and the ratio was no longer valid, the vessels were once again halted in the Kerch Strait for longer periods. When the Russian strategists wanted to look innocent in the runup to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea several months later, the delays of the vessels navigating to and from Mariupol and Berdiansk near the Kerch Strait shrank again (see diagram).

Under no circumstances, however, the duration of delays returned to the pre-blockade time. As Lithuania’s Foreign Affairs Minister Linas Linkevičius once described it aptly, it’s as if someone stole $1,000 from someone, returned $100 and everyone is happy that he is willing to cooperate.

Russian strategists use these ongoing violations of international law to test the limit of concessions and patience of the civilized world and its readiness to respond to Russia’s whims.

Based on this algorithm and earlier experience, it is fairly easy to forecast scenarios for 2020.

RELATED ARTICLE: Russia’s hybrid expansionism in the Arctic

The Azov sea port accounts for just a small fraction of exports compared to the other numerous ports in Odesa, Mykolayiv and Kherson. We are almost certain that the Azov crisis was a test. Ukraine’s key export routes are in the Black Sea leading to the Bosphorus.

From H2’2018, Russia has been increasing the number of navy ships and coast guard boats in the Sea of Azov. It sends new ships there and transfers the vessels engaged in the Caspian, Baltic and White seas via domestic river routes.

Next to the recommended Odesa-Bosphorus sea routes in the Black Sea are the oil drills located on Ukraine’s shelf and captured by Russia at the beginning of the occupation of Crimea. Few pay attention to the fact that these platforms at the Odesa field, also infamously referred to as Boyko drills, are closer to Odesa coast than they are to the occupied Crimea. The closest Russia-seized drill is 77.6km or 41.9 miles away from Odesa coast, 50.4km or 27.1 miles from the Snake Island, and 121.5km or 65.6 miles from Cape Tarkhankut. The closest drill to Kherson coast is just 52.2km or 28.2 miles away (see map).

Each platform and drill has long hosted a garrison of Russian special forces or marines, as well as radars for surface, underwater and air surveillance – in total, over a dozen Russian military objects on Ukraine’s shelf. While auxiliary boats patrolled them in the past, the 41st Missile Boat Brigade of the Russian Black Sea Fleet has been doing that since June 1, 2018 with 24/7 rotation and powerful battleships.

In one possible scenario, Russia could start halting the vessels heading to and from Odesa for check-ups. The FSB can easily come up with a report about a diversion group on one of the vessels with plans to explode the drills at the stolen Odesa field (which Russia considers its own in addition to the rest of the Ukrianian shelf where it extracts and steals up to 2bn cu m of gas annually). If Russia does so one, two or three times, the consequences for the traffic in that area are easy to see. This may not happen with proper deterrence, but that scenario should be on the table.

Another plausible scenario is a landing operation, possibly with diversion groups, on the Ukrainian Black Sea or Azov coasts. The Sea of Azov has almost entirely become a Russian lake by now as the Russians enjoy absolute domination there. Over the years of occupying Crimea, Moscow has seriously reinforced its Black Sea Fleet. As a result, Russia enjoys full advantage in the sea and may well be planning to use this advantage – especially in 2020 when the transit of Russian gas via Ukraine as a deterrence could disappear.

The problem of a landing operation is that it is impossible to guess where exactly it could hit. Ukraine’s entire coastline in both seas is vulnerable to such operations. How can Ukraine respond in the sea? All Ukraine’s government can do until it seriously reinforces its Navy, i.e. for the next 3-4 years, is ask NATO to have its military vessels permanently patrolling the area like they did in 2014. After March 2014, NATO ships patrolled the Black Sea almost 90% of the days until the end of that year. In our opinion, that prevented the outbreak of an “Odesa People’s Republic” on May 2, 2014.

In order to prevent such operations, Ukraine could try to create a sea border in the Sea of Azov in 2020. This means informing the world that the 2003 agreement on cooperation in joint use of the Sea of Azov with Russia is no longer valid, so Ukraine can unilaterally declare the area its territorial waters under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and protect this border with all navy and coast guard means.

Apart from the sea border, there will be more need for asymmetrical sanctions against Russia in 2020. It is highly likely that international economic restrictions will be imposed on Russian ports in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov for trips to the occupied Crimea as part of the “updated Crimean package” to replace or reinforce the “Azov package”. This could be effective deterrence against Russia in its intentions to occupy the Black Sea.

Clearly, Ukraine will further strengthen its marine capabilities in 2020. It might finally develop a proper sea policy in the context of real threats to the freedom of navigation in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, now finally recognized both domestically and internationally after 2018-2019. For now, Ukraine is still a state with land-oriented thinking and a habit of fighting wars on horses, carts, APCs and tanks.

RELATED ARTICLE: Hollywood on the Black Sea coast

Azov experience offers another source of hope: the halting of trade vessels during movement in the sea stopped when Ukraine’s Navy started escorting commercial boats from Mariupol to Kerch. It is therefore possible that ships from NATO countries could be invited to join Ukraine’s Navy in escorting or patrolling trade vessels along international sea routes.

One hopeful factor which the Russian strategists seem to have missed is that freedom of navigation is a fundamental principle of the civilized world that stands alongside freedom of trade and human rights. Therefore, engaging the international community in an effort to block threats to this freedom could also deliver some positive results in 2020.

By

Andriy Klymenko,

Institute of Black Sea Strategic Studies monitoring group

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook