Volodymyr Rashchuk is a well-known Ukrainian theatre and film actor, musician, and athlete originally from Mariupol. Together with his wife, Victoria, they volunteered to join a military unit in the early days of the Russian invasion in February 2022. Victoria was helping at the field kitchen while Volodymyr set off to face the Russian forces on the outskirts of Kyiv, from the side of Brovary.

* * *

Volodymyr Rashchuk didn’t go to the military enlistment office because he lacked military experience and had a deferment due to his health. However, this did not prevent the actor, who would later receive a call sign “Artist”, from earning an officer rank in the S3 section of the 3rd Battalion “Svoboda”, a unit of the Ukrainian Armed Force’s Operational Support Brigade “Rubizh”. He has gone through Brovary, Irpin, Bucha, Hostomel, Rubizhne, Severodonetsk, Bakhmut, Kurdyumivka, Ozaryanivka, Spirne…

Rashchuk says that he is now fighting in one of the most motivated units because “we are all volunteers here”. “I didn’t come for the money. We came there as fully-fledged individuals who were self-sufficient in their fields. We are entrepreneurs, actors, architects, hustlers. There are all the different types of people who have proved themselves very effective in this war. Once, a fellow soldier came and asked, “How much money do you get?” I said, “Vasya, before the war, for one day of filming, I would be earning 18,000 hryvnias [approximately 440 euros. – ed. ]. And I was filming constantly. Six months straight with no days off. So, what do you think motivates me now? I came here to fight for Ukraine”.

This and all the photos below: Ivan Yasniy

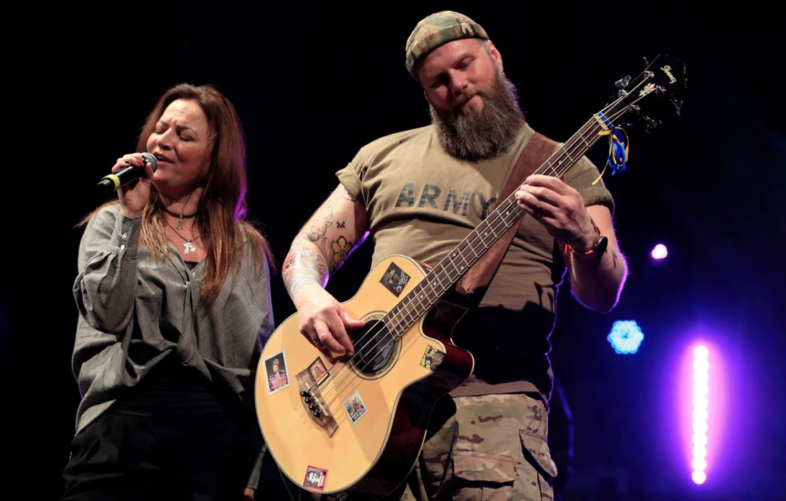

Rashchuk continues to fight, while in the breaks between rotations on the front, he even manages to act in movies and perform on stage. It was on the film set that we were lucky to meet and have a conversation. Gradually, we talked about everything, mainly cinema and war, though – because today, this is what our daily life is.

Below is Volodymyr’s direct speech.

* * *

The Film Set After the Trenches

It really triggers something. There’s Klava, an actress, sitting in the car. Suddenly, her cup fell down; she picked it up and said she would have to disinfect it to make sure it was clean to drink from it. And at that moment, I had a flashback of me drinking water from a puddle because I hadn’t had water for two days. I think to myself – we live in such different realities that it’s not just complicated, it’s practically impossible to explain. But there’s one story… I wouldn’t want girls and women to see things that my wife and daughter saw. My daughter now has such PTSD that she constantly trembles. She can’t film a video on her phone because her hands keep shaking. We’ve even consulted psychologists but to no avail.

I do feel like I live in different worlds. There’s one, and it seems to me that everyone should understand what happened to me. But that doesn’t always happen and it’s really hard this way. Sometimes, on a set, actors come to Kalashnikovs and start touching them. I say, “Hey, buddy, it’s been almost two years, and yet you still don’t know how it works?”

Now, there are those actors being filmed in military uniforms. They haven’t been anywhere, haven’t fought anywhere, haven’t held a weapon, and yet they are playing the roles of soldiers… Honestly, I think it’s disrespectful. Really, isn’t it better to invite a real-life soldier who will most certainly perform this role better than a professional actor? That’s my opinion.

Probably, I wouldn’t be able to handle any serious acting right now. But when it comes to buffoonery, satire — it’s just powerful. There [in the series “Code Name Tamada” – ed.] are such absurd circumstances the characters get into such comical situations. There is this character who hates Russians with all his heart and he has to get to the occupied territories to save the major’s daughter, who was evacuating people and got captured herself. And the only option is to do it under the guise of a DJ. In certain places, we completely rewrite the script because we want it to be realistic. Because not everyone understands what war is, and not everyone comprehends that it’s happening now.

What kind of movies should we be making now?

I think it’s smart to unload the horrors we are facing onto people right now. I find it difficult to understand civilians. They are scared of explosions. And I think I have 420 strikes per hour in my sector alone. And we already have different realities directly. But I understand how difficult it is for people who have never lived through it and who have not made the decisions I had to make.

Churchill once said if we don’t have theatre, cinema and culture, then what are we fighting for? I’m having similar thoughts. More than anything, I really want Kyiv and all our cities to live peaceful lives as if there were no war. But on the other hand, I want societal awareness. For people to understand that the war is ongoing. And that every day, our guys are dying out there. They die in excruciating pain…

Once, when I returned from Bakhmut, I didn’t even get my car cleaned. I did this so that when I’m here, in a relatively ‘quiet’ environment, I don’t forget the price we are paying to have it. There’s such a stench of dampness, diesel, and blood. My girls sat down, and my daughter asked, “What’s that smell here?” “Sweetie, that’s the smell of war”, I said. There were still traces of blood, things we couldn’t wipe off the fabric. That’s how it is.

Regarding movies, I believe we don’t need graphics. Everyone is overwhelmed and burdened enough. Of course, everything must be well-documented and filmed so that these stories don’t just disappear because, no matter how you think about it, our guys are dying. We may not have enough time. And on some level of buffoonish satire, black humour, I think today it’s very relevant. We’re not beating ourselves up there. In Severodonetsk, we didn’t shower for 26 days. 26 days! We hit a bunch of their equipment there; we targeted Kadyrov’s Akhmat unit. But the point is that we kept joking through all this time. And these jokes bordered on the level of evil and boundless evil.

I’ll tell you a few stories. Our commander is passing through; we’re standing in the passage near the windows, and suddenly, they [Russians – ed.] launch grad rockets. You don’t know where it will land; those missiles scatter everywhere. He steps back and says, “Quickly, move away from the windows, now! Not because I care about you, just because there’s no one else”, and walks away. We’ll all die. We are sure about that 100 per cent. But what matters is how you’ll get there…

So, if we’re going to make a story about war, let’s make it a dark comedy. It shows the level of our spirit and our truly carefree and brave nature. We don’t care how many of you [Russians – ed.] are there because we’ll win anyway.

We need to make light films. But with substance. I don’t like the vain, empty sketches. I like it when jokes reach a true absurdity, prompting people to realise really deep things full of meaning. We, directors and creative people are ready for this, but first, the stars must align.

The Profession

It helps a lot. Always. Everyone. It’s about communication, organising people, leading by example, making decisions. It’s the foundation that helped me grow from an infantryman to a squad and company commander; it taught me battalion management.

I worked at the Mariupol Theatre; I studied at Karpenko-Kary University for five years. For seventeen years, I worked at Lesya Ukrainka Theatre. I’ve had more than 20 leading roles performed in 28 plays per month. I have over 300 series, films, and everything that could be done over these years. I used to spend three months preparing for a movie; I took courses in extreme driving, became a professional stuntman, fell from the fourth floor, and learned to do anything myself. I trained with special forces, and even before the war, I knew how weapons worked, how an assault group operated, and how to clear the buildings. I know how to fight with cold weapons; I can ride a horse without a saddle. I know different languages. So, in a way, this is also my contribution to the profession. And I can work for 10 months without a day off. I’ll never say I’m tired – I will only be grateful for it. And when I see people not treating their profession the same way, it’s a betrayal for me. I honestly believe in it and act accordingly. When people don’t do that, it hurts me.

An actor is a person who is supposed to heal you. So, if you come to my play and you are hurting, your soul is in pain, I should share my emotions with you, and I hope that when you leave the play, you’ll heel. A musician has an instrument. He can change strings and tune it, and he’ll play. But for an actor, we keep it all inside. You can’t get sick, you can’t oversleep, you can’t do anything. These are all elements of the profession. You can’t treat people poorly because you work with them. These are details. But if you don’t have that, what’s your weapon, what can you share and how can you heal someone in pain?

The Return

When there was an opportunity to act again, I decided to go all in. I had a night shift from four in the evening until nine in the morning. And by ten, I had to be on another set. I move there, and there’s a full day until ten in the evening. And they ask me, can you handle it? It’s been more than a day since I managed to sleep. But one thing is doing military work that doesn’t bring you satisfaction and you’re forced to do it to survive, and here you’re practicing your own profession. I go out and say, “God, thank you for giving me this day; thank you for granting me work”. Well, it’s pure bliss. People don’t appreciate this. They can’t understand how important it is.

The Language

The thing that annoys me the most in Kyiv is the language issue. I don’t understand why people are so screwed up. Why is it that they don’t grasp the basics? And perhaps, this is the case when it’s impossible to rely on societal awareness here. On the state level, this [Russian language – ed.] should be prohibited. You should never get a job if you can’t speak the state language. You should never achieve anything if you don’t have a fluent command of a state language. Yes, just like in any civilised country. But, unfortunately, in our case, things are completely different – it hurts so bad.

Why did the war start? Because Putin was tricked. He was actually sure that things were really bad here, and perhaps, another five years down the line, their propaganda would have eaten us alive, and they would actually come in with a parade. He miscalculated the timing. But the Russians didn’t give up, and they continue working on it now. They have an extremely powerful propaganda machine, and they know how to do it. Now, with Arestovych, Boyko, who appeared in the background, and now Loboda [Russian-speaking singer – ed.] getting involved—this is complete madness. Yet, they influence people’s minds through social media, they have subscribers, and they really hit their electorate. Because this idiot [Arestovych, ex-presidentail adviser – ed.] will definitely run for office, and that’s the beast that brought the war here in the first place.

My own Ukrainisation

There was this meme that you fell asleep on fevral [February in Russian – ed.] 23rd, but you woke up on liutyy [February in Ukrainian – ed.] 24th. That’s exactly what happened to me. We lived in Vyshhorod. We saw those Russian helicopters flying over the Kyiv Sea; we saw the Ukrainian Armed Forces shooting them down. And it just snapped in me. I continued to speak a rustic surzhyk [a Ukrainian-Russian pidgin dialect, sometimes used in Ukrainian territories once colonised and Russified by Russia – ed.], a broken language, gradually improving, but I never switched to Russian again. Never.

But let’s look at it from another perspective. Now, we don’t have a direct connection with our ancestors who fought for the survival of Ukraine and its language. There are no Sich Riflemen [Ukrainian People’s Army unit operating in 1917-1919, – ed.], no UPA [Ukrainian Insurgent Army – ed.] here now. Just like back then, they also didn’t have a connection with the Cossacks or Kyivan Rus. But it’s something we feel at the genetic level. It’s something in our blood. When you stand on your land and realise that you are Ukrainian. For me, over these two years, there has been a true transformation. I regained the sense of who I am. I really went to war without thinking about it, only realising it later. As pompous as it may sound, I was ready to die so that the Ukrainian nation would exist. This is the idea of Ukrainian nationalists, for whom life itself has no value because language, culture, heritage, history, and land are more important. Ukrainians are phoenixes. People who are reborn from the ashes. These ashes are sprinkled with the blood of our ancestors. And that is our strength. On some intuitive level, I felt this.

Language is the only thing that can unite us anywhere. For example, we were in a war zone, and there were two Lemko villages. There was the same school where Sosiura [Volodymyr Sosiura, Ukrainian poet and writer – ed.] studied. This is in the Luhansk region – and the local population there speaks Ukrainian.

You know, some people [civilians – ed.] say, during the war, soldiers in the trenches speak Russian too, and that’s fine. But honestly, in our unit, nobody would speak Russian. None. Because if someone speaks Russian, that’s it – either they were captured or the Russians got our radio.

Language is our identity. I swear, it physically hurts me when people say, “Well, but what’s the difference?” My birthday is on October 11th. And it was my first birthday when everyone congratulated me in Ukrainian, except for three people. My dad is in Donetsk; my mom is in Greece, and my sister, who’s in Frankfurt—three people who sent me their wishes in Russian. Well, I can’t insist that my parents switch to Ukrainian because they are old. But I told my sister. And she says that it’s the language of her childhood; her mom used to sing her lullabies in Russian. I said, “Sister, you left the Mariupol drama theatre five hours before Russians bombed it, you spent three days evacuating from marching Russian troops to Zaporizhzhia, and only 60 out of 120 cars in your column survived and made it alive”. And still, she says it’s “my problem”. She doesn’t learn. There are many people who are aware, but there are many others who don’t understand why there is a difference. Therefore, I believe the use of Russian should be banned at the state level. There are no other options. Otherwise, it’s a trouble.

The War

The war’s outcome greatly depends on the geopolitical dynamics and the situation on the front. As they say, nobody judges the winners. If we defeat the enemy, then the question will be open for us. But if we don’t, something I don’t even want to think about, then as Russians say, “Russia will end where the Russian language ends”.

When the Russians attacked Kyiv, all of Ukraine rallied together. If a driver could find a car—he evacuated people; if he could find socks—he found them; if he could find a shelter—he found it; if he could take up arms—he took them, and there it goes. No one thought that they were not good, experienced enough, or didn’t have the skills. Everyone just rallied and stepped up. That’s heroism. That’s the nation. And, in fact, this is true statehood.

We were the first in the brigade to start using FPVs. They turned out to be so effective that now our normal numbers are 300 per month. We’ve burned 14 tanks and 30 armored vehicles. We lost 24 heroes in three months, but we’ve eliminated about a thousand ‘bastards’ [Russian soldiers – ed.]. We are in a lowland, and they are 90 meters higher. They see everything through cameras, all our logistics, everything. It is a highly complicated territory.

Authorities won’t approve a UAV unit in our battalion. In the last rotation, we had a UAV unit: large strike drones, Mavics, reconnaissance drones, FPVs, and Lelekas [‘Stork’, Ukrainian-made drones). We covered the front line, acted as counter-battery, and hit distant targets; we transmitted coordinates – this is how the war evolved. Now, without drones, you’re nobody. We’ve devised a plan and said that we needed a unit now. The commandment tells us it’s impossible. We say that the personnel needs to be expanded and that we need people for intelligence who will engage in espionage. They tell us there are such people in the brigade, what more do you want, where are you getting involved? Now, we found tracked vehicles for mine clearance, for kamikaze attacks, machine gunners and evacuators. They [commandment – ed.] also prohibited us from buying them, although it’s our money. Ordinary people are donating us money for this, but the funds go through the centralised system. Now, what do we have? A smaller Soviet army fighting the bigger Soviet army. We have certain successes. But the “bastards” are learning quickly.