One single event and the subject of war instantly takes top place in the list of things that worry ordinary people. In Kyiv, which is relatively far from the frontline and from both Ukrainian seas, people started buying up groats in grocery stories and hard currency at exchanges. Snatches of conversation in the streets echo the phrase “martial law,” even when the conversation is among hipsterish girls with steaming lattes in their hands – and the tone quite disgruntled. And that was even before the Verkhovna Rada convened to discuss the president’s proposition.

The range of reactions among ordinary Ukrainians was hardly a surprise. Nor were the informational attacks that appeared that same day in the social nets. “Ordinary citizens” wrote about urgent mobilization, levies because of martial law, and other fakes of varying degrees of plausibility. The next morning, you could already hear people saying in their offices that men would be “taken right off their trains and enlisted in the National Guard.” Depending on the kind of company, the main focus of these insatiable recruiters would likely be programmers, or drivers, or just about anybody who went out of their home for bread and matches.

There are also calls to maintain the peace, offer sober assessments of news in the press and help the military. This was common during the Maidan and whenever things escalated at the front. It’s easy to predict the consequences as well: stores are increasing their inventories of groats as the price goes up, the dollar will not hit UAH 50, and the subject of war will soon be replaced once again by talk about utility rates, the latest video from a popular musician, or the weather. It’s disappointing but natural. Moreover, if the choice is between a “festival of fear” and indifference, the latter doesn’t seem like the worst option in the world. For those for whom war is a daily reality, nothing has changed and nothing will change.

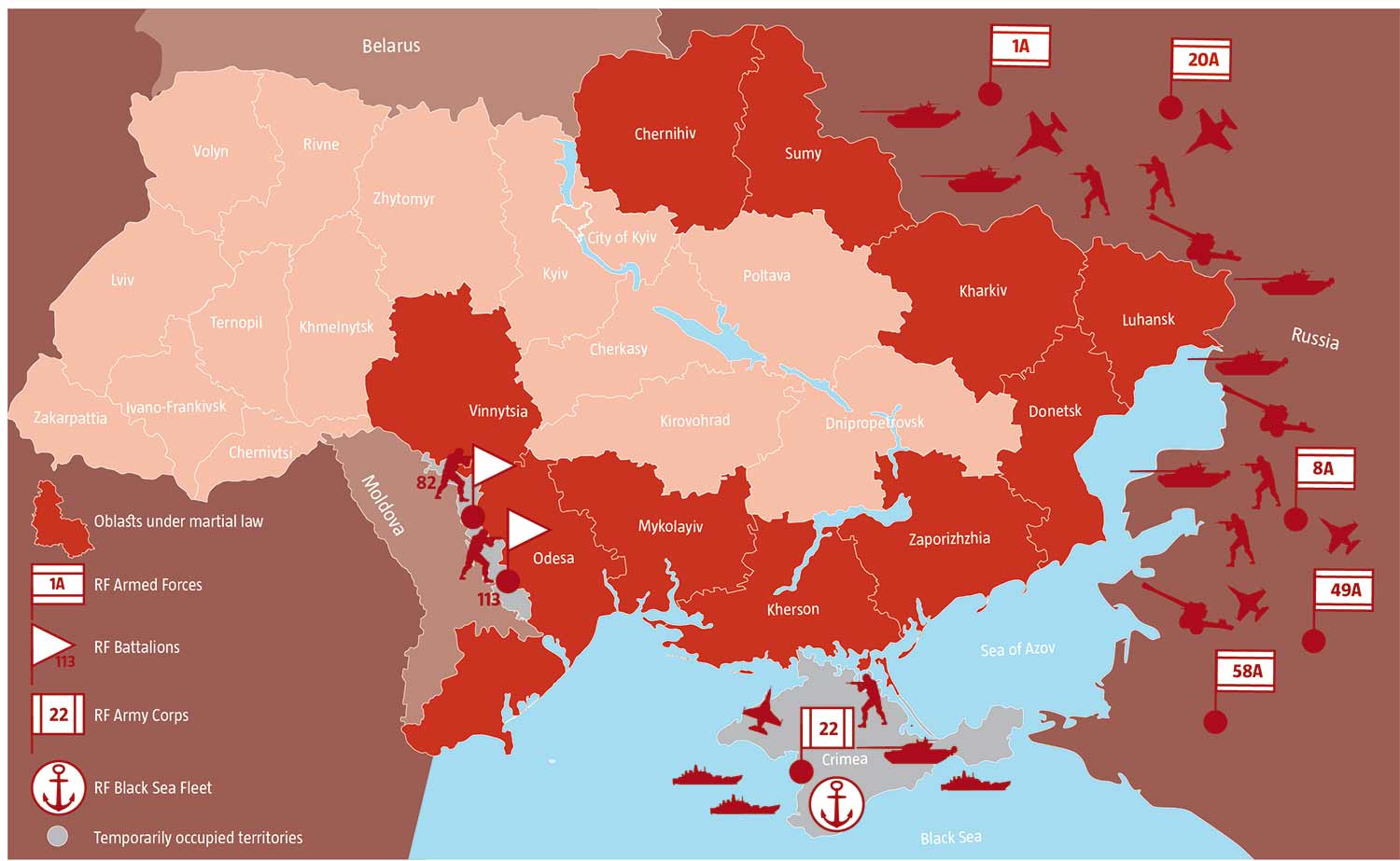

The bare bones of what happened at the evening session of the Rada on November 26 was that 10 oblasts would live under martial law for at least a month. The main law that regulates the situation during this period is called “On the legal regime of martial law.” The third and fourth words in this phrase are often left out, but the emphasis should properly be on them, and not the last two. The main point is the legal regime, and not the loss of rights and dictatorship. When the emphasis is shifted, it becomes possible to understand the main features of this state.

RELATED ARTICLE: Combative precautions

First of all, the thing that worries so many Ukrainians: mobilization. The answer is short and sweet: no mobilization is underway in Ukraine right now. Not even in the 10 oblasts where martial law has officially been declared. For starters, mobilization has to be announced through a special presidential decree that also establishes how many are to be mobilized and for how long. And this example is true of the rest of the issues related to martial law as well: the government gains more power, but this is not to say that will take advantage of them. Even if they are to be used, a special procedure has to be followed, just as under normal circumstances. The conditions for applying any new powers were clearly delineated by the president during his address to the Rada: “I want to emphasize separately: this will be applied only in the event of a land attack by Russia.” In other words, the main condition is a possible offensive operation by Russia. If this were to happen, it’s unlikely it will much matter at that point whether the Rada’s decision to mobilize has the force of law or a presidential decree does.

“The decree instituting martial law allows the government to introduce restrictions,” says Volodymyr Vasylenko, one-time Ukrainian representative on the council for human rights at the United Nation. “That is, it’s not imperative. This is already considerably mitigated. Everything will depend very much on the actual situation that develops in a given oblast.” Vasylenko says that the average person is unlikely to suffer as a result of this new legal state and notes that martial law is not something Ukraine invented, either.

“A state of war should be differentiated from martial law, which many Ukrainians actually don’t understand and even some of the country’s leadership doesn’t understand, although the Constitution talks about it – admittedly not entirely clearly,” Vasylenko explains. “A state of war is a regime under which armed forces are used in response to the use of armed force by an aggressor country. This affects only the procedure for applying force against an enemy. Martial law establishes a restrictive regime for specific civil rights within the country itself. It’s normally instituted to establish the most helpful conditions within the country to repel the aggressor, including to counter enemy agents, fifth columns, useful idiots and so on.”

In the past century, nearly 20 countries around the world have declared martial law on their own territories. Among the most recent examples are Egypt, Thailand and Turkey, although even Canada declared martial law in Quebec in 1970 during the October Crisis. Turkey declared martial law in 2016 after an attempted coup and maintained this state for two years, a period noted for the persecution of opposition military personnel, journalists and activists. Still, in all four cases, martial law was invoked in response to a domestic crisis, with the ensuing political consequences. In Ukraine’s situation, the threat is external. This reduces the risks that martial law will be abused for domestic political purposes, although it does not completely eliminate them.

Among the possible consequences of declaring martial law that generate considerable unease among ordinary citizens are the setting of curfews, restrictions on travel and the expropriation of property for defense purposes. If people assume such a possible development and wish to evaluate it, they should first re-read the presidential decree that the Verkhovna Rada approved. At the time this article went to press, two key elements that were written into Points 4 and 6 were absent. Firstly, the Cabinet needs to enact a plan for how implement and ensure measures under the legal regime of martial law. This is the document that would determine which agencies responsible for enforcing different restrictions. Moreover, oblast administrations and local governments would have to establish defense councils locally. In case of escalation, this is who would bear responsibility for specific actions and for issuing the relevant legal acts. Quite a few government agencies would have to take on responsibility that don’t necessarily fall under the presidential chain-of-command, such as the Interior Ministry and the police.

In any case, interfering in housing or, say, taking away the right to an education without justification –the kinds of things that Yulia Tymoshenko and Oleh Liashko were scaring the public with during the Rada session – would definitely not be happening. For one thing, any such moves require separate determinations and legal acts to be issued by the responsible agency. Otherwise, there are always the courts. Indeed, the law on martial law clearly states that Ukraine’s judiciary will continue to work as usual and prohibits setting up emergency or special courts.

While the everyday situation is pretty clear, the political implications are far less so. According to law, the president has three main advantages that he can use for his own purposes. First is the option of raising the question of banning public gatherings and parties that are engaged in anti-Ukrainian activities. However, the law clearly states: “in such order as is stated in the Constitution.” The Basic Las allows such bans only through the courts, while the courts are continuing to operate in standard mode. It’s hard to imagine that they might stop the activities of even a single organization during the course of a single month.

The second advantage is the option of setting up military administrations at the local level. In January 2018, the Verkhovna Rada passed a substantial set of changes to the law on martial law. Most of these innovations dealt precisely with the way that local governments would work under martial law. Briefly stated, the president was given the option to replace local councils, mayors and village heads with military administrations. Under the law on martial law, this can only be in effect as long as the special regime is in place, with the exception of cases where the councils and heads resign on their own. However, the document specifies the pre-term “termination,” not the “suspension” of the powers of local councils. How a court of law might interpret this nuance is not known. In other words, hypothetically, it could all simply lead to a snap election. In principle, the president can use such an opportunity to increase his influence at the local level, so setting up military administrations is not necessary.

The third presidential advantage is in the prohibition of elections during a state of martial law. Plenty has already been written about Poroshenko’s attempts to postpone their scheduled dates by instituting martial law. However, the situation currently looks like this: martial law has been instituted for 30 days and the election will still take place as scheduled, on March 31, 2019. To affect this, the president would have to extend martial law for another month, but the procedure for prolonging it is the same as for instituting it in the first place, and so the Rada will have the last word.

RELATED ARTICLE: Russia’s Azovian knot

Today, the only ones who are suffering from martial law in the political arena are a series of new unified territorial communities (UTCs). The CEC set the first elections for 125 UTCs for December 23, and not all 125 are in oblasts where martial law has been declared. However, those UTCs whose elections will not take place will see their budgets shrink next year – unless the Rada makes the necessary amendments…

Altogether, then, it’s clear that the law on martial law itself does not offer the president any unambiguous advantages in relation to the upcoming elections. So the reasons for why this decision was made need to be sought elsewhere. It’s hard to say whether one month will be enough to significantly improve the country’s defenses, but a significant signal has been issued to the international community. The institution of martial law could be used to strengthen Ukraine’s position in international courts where it is suing Russia. But the main impact is that Ukrainians have once again focused their attention on the war. “Army” is the first word on posters belonging to the current Head of State. So, at least for December, President Poroshenko has taken the lead in the information space.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook