History offers many examples of how dense networks of good roads ensured lasting unity in very heterogeneous state formations, such as the Roman or Inca Empires. In the recent history, the construction of railways followed by automobile roads contributed to the consolidation of the huge United States and the integration of Germany hitherto divided for centuries. Meanwhile, a lack of proper communication infrastructure ruined many states as their different parts developed as semi-isolated corners of empires, alienated from the rest of the country. Quite often, these alienated corners were better connected to the neighboring countries than their own state and drifted apart from it gradually but inexorably, unless they were reconnected by newer transport arteries in the process of industrial upheavals.

Stitching the fabric

Today’s Ukraine is heading to a point where it has to choose the path it will take into the future. Technical degradation and obsolescence of its two major transport communication systems that used to connect different parts of the country has gained a dangerous pace in the past few decades, even by comparison to the poor situation in which they had been in the late years of the soviet occupation.

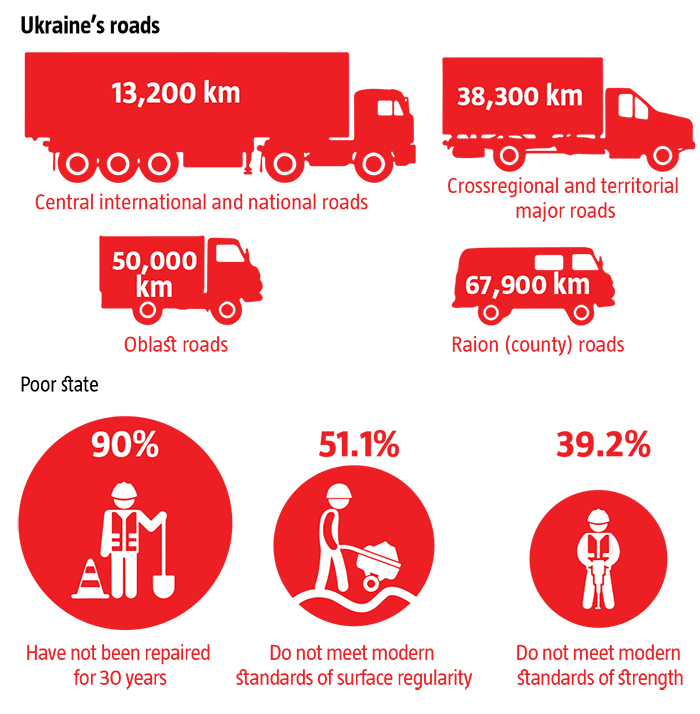

Ukraine has nearly half a million kilometers of automobile roads. This includes nearly 250,000km of urban and rural streets managed by local authorities. Some roads in Ukraine are privately owned or are part of the territory of enterprises. State roads of all categories account for 170,000km. On one hand, their density is 6.6 times lower than in France, a country comparable to Ukraine size-wise. On the other hand, this amount of road surface creates a big problem of maintenance, let alone upgrade. Given the deficit of funding, 91% of automobile roads in Ukraine have not been repaired for the past 30 years. Therefore, 39.2% of them do not meet modern standards of strength, and 51.5% — of surface regularity.

RELATED ARTICLE: Russia’s Azov blockade. How the Kerch bridge built by Russia blocks and threatens the ports in Mariupol and Berdiansk

There are only a few hundred kilometers of highways in Ukraine compared to 12,500km of autobahns in Germany which is 1.5 times smaller than Ukraine, and 7,100km in France. Also, Ukraine has a mere 2,200km or 1.3% of category I roads – these must have a divide line and two-four lanes in one direction – and they are still far from European standards. As a result, the average speed of movement on Ukrainian roads is 2-3 times lower than it is in Western Europe. This makes long distances between different parts of the country even longer. Moreover, these roads are concentrated unevenly, mainly in Kyiv, Zhytomyr, Dnipro and Kharkiv oblasts, while a number of other regions barely have any.

In the last decade, the amount of funding for road construction and repair never exceed a third of what was minimally needed to maintain and fix Ukraine’s network of automobile roads. The funding situation for local roads has been even worse. Their gradual shift to be managed by local authorities and local communities following decentralization will not necessarily improve the situation. Problematic and depressed regions may see continued degradation while decentralization of corruption in road construction can make struggle against it more difficult by increasing the ranks of potential kickback receivers. Stitching the country back together and stimulating more equal economic development that could fully reveal the potential of the entire nation and all of its territory means that all automobile roads across the country must be developed, not just the most important ones.

On the bandwagon of the past

As automobile roads in Ukraine are of poorer quality compared to roads in the EU and fewer people own cars, railways still dominate the transport sector. They carry 58-60% of freight and over 40% of passengers.  The major role of railways in a nation’s transport system reflects the potential it had in a distant past – cars replaced railways in freight and passenger traffic in developed countries in the second half of the 20th century. Meanwhile, the quality of railway infrastructure in Ukraine is moving farther away from the needs of both the industry and the passengers every year.

The major role of railways in a nation’s transport system reflects the potential it had in a distant past – cars replaced railways in freight and passenger traffic in developed countries in the second half of the 20th century. Meanwhile, the quality of railway infrastructure in Ukraine is moving farther away from the needs of both the industry and the passengers every year.

On one hand, Ukraine’s railway network is still unparalleled in Europe (excluding Russia) in terms of rail freight traffic. With 340mn t in 2017, it carried over 25% more cargo than Deutsche Bahn, another major railway carrier in Europe. Exports, imports and transit account for most of this traffic but the share of domestic traffic is growing slowly: it was hardly over 1/3 of UkrZaliznytsia’s total traffic several years ago and has climbed up to nearly 50% now. The rates for domestic transportation within Ukraine are among the cheapest in Europe and the world. Still, they generate revenues for Ukraine’s railway operator. The main source of income, however, is the downplaying of depreciation and investment costs which hampers the sector’s modernization and development.

UkrZaliznytsia’s passenger traffic is 12 times lower than that of Deutsche Bahn. It has been reporting losses consistently for many years. Ukraine’s population is half of that in Germany but the distance between different parts of the country is far longer. One would expect this to encourage people to travel in trains more. Moreover, the state of roads and underdeveloped air transport create far less competition to the railway transport in Ukraine compared to the wealthier Germany.

In fact, lower rail passenger traffic in Ukraine reflects the critical state in which this transport sector has found itself. The key problem is the insufficient use of railway potential by Ukrainians. This is because of the flaws of Ukraine’s train services, poor quality of many passenger trains and slow movement in most directions. These aspects are less important in freight traffic but very important for passengers.

Given the scale of investment in Ukrainian railway transport in 2017-2018, it is too optimistic too expect the implementation of even the modest plans to invest UAH 150bn (approx. EUR 4.7bn) into its development over a five-year term by 2021. This is less than half of over EUR 10bn invested in Deutsche Bahn annually. Ukraine’s investment program of EUR 4.7bn allocates a mere EUR 0.9bn to buy new locomotives, EUR 300mn to modernize and repair the available ones, and less than that to buy 400 new passenger cars. At this pace, new trains will not replace the vehicles to be written off over this period, let alone the obsolete trains. As a result, the deficit of proper passenger trains will increase.

Over the years of independence, state rail transport in Ukraine has been a donor for private and mostly oligarch-owned business, allowing it to save on freight rates. Its representatives insist that their business will start having losses if the rates are raised. Also, they claim that the current freight traffic is highly profitable, although they speak of the purely operational part without mentioning investment into the upgrade of railways and trains. Until recently, Ukraine had a deficit of freight train cars. It often undermined output and export plans of agriculture and steelwork businesses.

The purchase of new train cars – by UkrZaliznytsia and private freight owners that use them – has somewhat shifted the problem in the past years towards the deficit of locomotives. Meanwhile, the major clients of rail freight traffic are proactively elbowing UkrZaliznytsia out of the freight traffic sector by using their own train cars and locomotives.

Access of more private players to rail transportation can encourage competition in this industry and spur business development in Ukraine. Still, such steps must be fitted to the wider strategy for developing rail transport in Ukraine. One thing that needs to be done is a radical change of the share of funds allocated for the development, upgrade and electrification of railways at the expense of the companies that want to work on them. The old policy allowing them to do cherry picking while not investing in long-term development of Ukraine’s transport potential has been a key factor of the past 25 years that delivered windfall profits to offshore shell companies owned by oligarch businesses as the railway system degraded at the same pace.

Another practice to be stopped is the subsidizing of passenger traffic by railway companies. This social function should be fulfilled by the national and local budgets, while ticket prices – especially for local traffic – should be raised to a level where they will fund the development of quality passenger services. Stopping cross subsidization and shifting revenues from freight traffic to investment can create conditions for Ukraine’s railway system to turn into a modern and effective instrument for bringing different parts of the country closer together, and spur economic development. More investment can also create more domestic demand for materials and equipment necessary to meet this growing demand.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Kremlin's gas pipelines bypassing Ukraine are a threat to the country's energy security. What can it do to protect itself from upcoming risks

The realistic scale

This highlights yet another problem that stands in the way of rail growth in Ukraine. The political leadership and companies responsible for shaping the demand for its services have a very shortsighted vision of how this transport can develop in Ukraine. The development of both railways and roads should be accompanied by a dynamic growth of small and medium-sized businesses that will service these railways and roads, the flow of freight and passengers, as well as the construction and maintenance of roads and vehicles. A trend whereby a lion’s share of investment in the transport infrastructure flows out of Ukraine to import components, maintenance or installation services, is unacceptable.

This does not mean that Ukraine can do without purchasing foreign-developed designs, technology or components. For now, Ukrainian companies are often unable to offer a competitive product that meets the best standards. Still, imported technologies should be bought indirectly via Ukrainian business. Ukraine cannot afford to just reject an opportunity to produce most components needed to maintain its roads and railways domestically.

This requires a state strategy aimed at replacing owners and managers at the current enterprises unless they can adapt to the needs of the present day, or at creating new facilities where there aren’t any. The  share of localization in the production linked to the construction of roads and anything else it takes to carry and service freight and passengers should be 50% at the very least. An import-oriented model should not be the goal. Transport network development should become one of the key instruments in upgrading and improving the country’s economy.

share of localization in the production linked to the construction of roads and anything else it takes to carry and service freight and passengers should be 50% at the very least. An import-oriented model should not be the goal. Transport network development should become one of the key instruments in upgrading and improving the country’s economy.

The choice today is not just between triggering an active development of roads and railways or letting them degrade further. It is also between letting Ukraine develop in a colonial or neo-colonial vector – when a handful of crossborder transit arteries develops while domestic infrastructure slips into further degradation and the already weak network of domestic connection gets even looser – or turning the development and reconstruction of the road network into a priority, putting an accent on strengthening links between different parts of the country and making intense movement of passengers and goods between the country’s center and remote parts more accessible. In the latter case, Ukraine’s transit potential and communication with the world – an undeniable crucial component as well – will be the continuation and result of a widespread and quality system of transport channels created with an initial focus on domestic development.

Otherwise, Ukraine risks aggravating a situation where it is easier to travel or carry goods between some parts of the country than between its remote areas and the center. That could lead to a situation where Ukraine or some of its regions turn into a supplement for the transport systems of other countries.

While in the soviet time all of Ukraine’s roads led to Moscow or from Moscow to the key points at the borders or in seaports, the past few decades have seen investment into the construction and maintenance of roads and railways for international transit corridors, even if this funding comes from foreign loans guaranteed by the Ukrainian government. Internal financial resources of UkrAvtoDor [Ukrainian Road Operator] and UkrZalisnytsia are also channeled for these purposes. These transport corridors are indeed very important for Ukraine and its economic development. Yet, as the domestic network of roads is deteriorating, the gap deepens. It should be overcome by cutting investment into international transport corridors while maintaining or increasing investment into the development of the domestic transport infrastructure.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook