In March 2012, Viktor Yanukovych promised that Ukrainians would be able to take out 10-15-year mortgages with a 2-3% interest rate. Commercial banks now charge an average of 20.5%, with the difference supposedly being compensated by the state. UAH 1bn has been allocated from the budget under relevant legislation. The programme is already working – on paper, that is. Cabinet of Ministers Regulation Nos. 343 and 465 determined “the procedure for reducing the cost of mortgages to provide affordable housing to citizens who need better housing conditions”. Recently, with a relevant PR campaign, officials even reported about the first lucky people who have received these preferential loans. Initially, the plans for resolving the housing problem were ambitious and specific: 30,000 people by the end of 2012, or 2.6% of the 1,138,000 officially registered on the housing list. However, this item was removed from the government regulation in late May. This and many other facts show that “a cheap mortgage from Yanukovych” is yet another empty project, designed to gain support. Another example is the PR on the programme to compensate the losses of the victims of the Elita Centre construction fraud, on behalf of Kyiv mayoral candidate Oleksandr Popov.

THE SCALE OF THE HOUSING PROBLEM

One in seven Ukrainian families have less than 7.5 m2 of living area per person, while a mere 50% of families live in more than the “sanitary norm” of 13.65 m2. Taking into account the salary level, the average Ukrainian has to work at least 20 years to buy a two-room flat, while Americans need only 2.7, Germans 4.4 and Brazilians 6.3 years. The absence of own housing is the main deterrent to marriage, causes divorce among young people, leads to the decline of the birth rate and adversely affects the overall demographic situation. About half of the surveyed young couple say that the main reason for putting off having children, or even not having any at all, is the absence of adequate housing conditions. Nearly 31% do not have a roof over their heads; 14% rent flats; 10% are crammed into hostels and 11% in communal flats. A mere 33% of young families and 56.3% of all families have separate apartments.

Periodically, youth organisations stage protests, demanding that the constitutional right to housing be realised in practice, reduced mortgage rates, increased budget spending on affordable and social housing, as well as a reduction in corruptive pressure on the construction industry. However, what these protests achieve at best, is the resolution of housing issues for their leaders and the activists of “public movements” associated with them, on the basis of which, the government is able to report that it is “listening to everyone” and in essence, indefinitely postponing any real resolution of the problem.

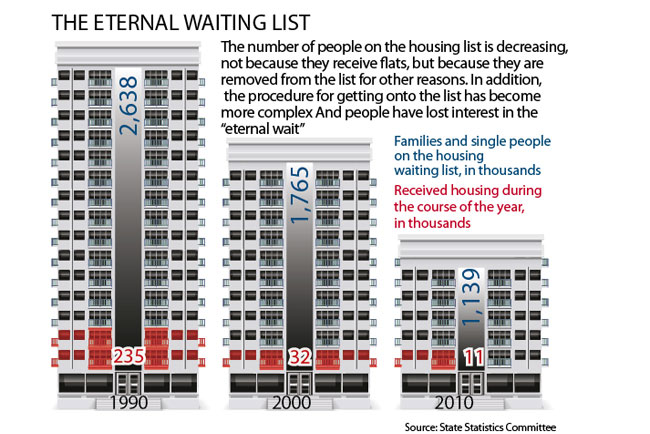

There are several programmes in Ukraine supporting the construction of affordable housing for young and underprivileged citizens, but they are independent of each other and often not coordinated among themselves. Their efficiency remains surprisingly low – less than one percent of those in need have experienced improvement. In recent times, various state programmes have provided housing for no more than 11,000 of the 1.1 million Ukrainians on the housing list. The majority of Ukrainians no longer believe in the efficiency of official “housing lists”, so the actual number of the “homeless” is at least five times higher. This situation creates unequal conditions, provokes corruption and favoritism and discredits the very idea of a housing policy. For example, according to the Audit Chamber which audited the Fund for the Promotion of the Construction of Housing for Young Families, only 12% of its housing construction quota was fulfilled. Loans were secured for less than three percent of young families that participated in the programme. In rural areas, only two (!) families received housing from this agency since the time that it was set up. Another example: in Kyiv, where there are approximately 130,000 people participating in the state affordable housing programme alone, in 2011, Kyivmiskbud, the municipal construction company, built only 355 at which, government aid did not exceed 30% in 1/3 of these cases.

MIRAGES

In essence, Yanukovych’s much touted mortgage programme contains mutually exclusive norms that disqualify the absolute majority of those in need of housing, and subsequently turns the initiative into yet another propaganda fiction.

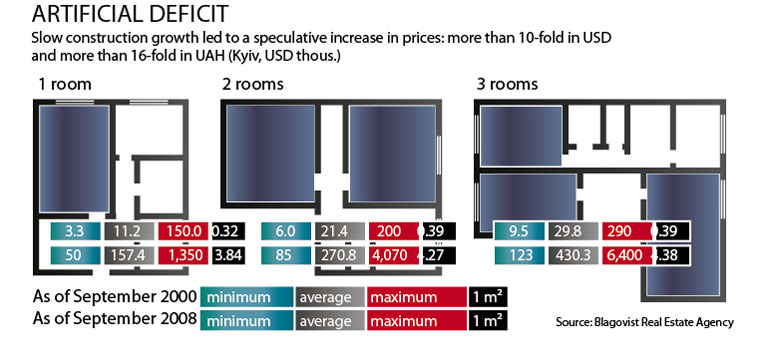

Within the limits of this initiative, the acceptable maximum cost of one square metre of housing is set at up to UAH 7,000 for Kyiv, up to UAH 5,000 for Kyiv Oblast and UAH 4,000 elsewhere. However, these prices are virtually nonexistent on the real estate market of Kyiv and in the regional centres of Kyiv Oblast. Moreover, the government is not proposing any mechanisms to cut prices, particularly the elimination of the price-inflating corruption component. And this is understandable, because these reforms in the construction sector would inevitably cut the flow of money to many officials who thrive on bribes from developers. Instead, the government is asking citizens to simply pay the “extra” cost out of their own pockets.

There are also many other nuances that discourage people from dealing with the state. Should a bank agree to grant a mortgage on preferential terms, the buyer must choose a flat in a building approved by a government commission of the Ministry of Regional Development, Construction and Housing and Communal Services of Ukraine, based on the proposals of local state administrations, then he/she would have to sign two contracts: one to purchase the flat (between the purchaser, the bank and the developer) and the other one to receive government compensation (between the purchaser, the bank and the local state administration). Thus, if the government refuses to make good on its essentially pre-election promise of compensation, it is unlikely that the citizen will be relieved of his/her previously assumed commitments. Meanwhile, the government will not be held responsible, because the compensation of part of the interest rate is transferred to the buyer’s personal account by local administration bodies. They, and not the central government, will be held accountable if things go wrong.

At the same time, an amendment to the Cabinet of Ministers’ Regulation now makes it possible for the buyer to sell the “affordable” flat to anyone (rather than a person who meets the programme’s criteria), thus facilitating corruption.

LOOKING OUT FOR NUMBER ONE

The government does not conceal the fact that housing programmes are aimed at solving not so much the problems of the population, as those faced by construction companies and enterprises in associated sectors. When presenting the initiative, Yanukovych said that it will drum up business for construction companies and building material manufacturers and will stimulate demand for Ukrainian metal products on the domestic market. These words may refer to a coterie of close associates, particularly in view of the currently existing budget distribution system. So nice-sounding declarations may only be a convenient excuse for allocating several hundred millions or even billions from the state budget to banks and developers closely linked to the government. These fears are already proving to be true. According to information obtained by The Ukrainian Week, small companies that would like to participate in the programme, cannot find a common language with the officials responsible for granting access to it. Rumours about demands for kickbacks are rife on the market.

That the government’s initiative may be aimed primarily at supporting large construction companies, indirectly linked to the country's leadership, is also corroborated by an array of measures taken to cut the cost of building affordable housing. The fact that supply and demand determines the price in a market economy is ignored. Thus, the way in which this problem can be resolved is by a significant increase of supply. Otherwise all efforts to cut the prime cost of construction and mortgage servicing will quickly translate into additional revenue for developers and the officials to whom they have connections. This conclusion is also confirmed by well-informed market participants.

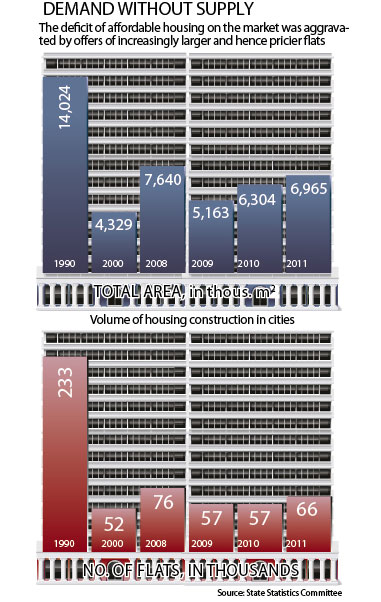

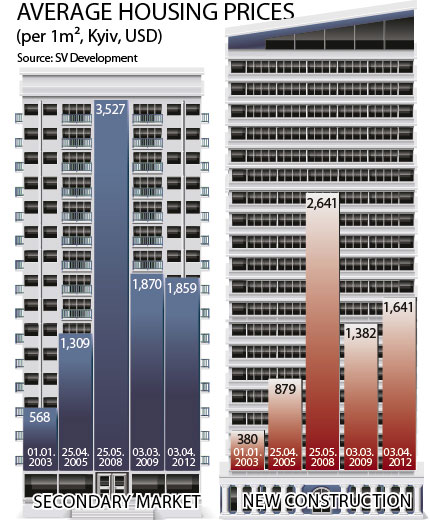

The experience of the 2000-2008 construction boom proves that the Ukrainian market was controlled by several large companies. They appear to have entered into a classic price-fixing agreement. As a result, instead of increasing supply under conditions of progressively increasing demand, they tried to check the construction growth rate in order to drive up prices. Thus, while dollar prices skyrocketed, construction volumes did not even double.

Another problem is the unwillingness of developers to build truly economy-class housing, whereby 40-50 m2 are used for a two-room, rather than one-room flat. Simple calculations show that it is more cost-efficient to build large flats. This factor was one of the key deterrents to solving the housing problem, because the number of flats commissioned during the construction boom of 2000-2008 increased by 46% (from 52,000 to 76,000), much more slowly than their total area (by 77%, from 4.3 m2 to 7.6 million m2). The average living area increased from 83 m2to 100 m2. Paradoxically, it continued to grow, even during the crisis, exceeding 110 m2 in 2010, while the number of flats declined to almost to 2000 levels (57,000). This trend in itself is a powerful factor in the aggravation of the housing problem, because Ukrainians need flats rather than square metres. Moreover, it is obvious that a city flat with an average area of more than 110 m2 cannot be affordable by definition. Meanwhile, state programmes often encourage this megalomania, which is at variance with the real capabilities of the state budget and the purchasing power of most citizens – even the middle class, to say nothing of the underprivileged. For example, under these state programmes, a flat for a family with two children should be at least close to 100 m2.

OVERCOMING POVERTY

Existing approaches to solving the housing problem under market economy conditions cannot be efficient, because a shortage of budget funds make it a priori impossible to secure equal access to relevant programmes for all citizens. At the same time, there is no pressure to demonopolise the construction sector and eliminate corruption within it. The sporadic allocation of flats to an indecently small number of people on the list (1-3% of the total), backfires, provoking abuse and stimulating a parasitic attitude within a large part of society. As a result, the housing problem remains unresolved, while social attitudes are deteriorating: a generation of citizens is emerging in Ukraine, who do not and cannot have a roof over their own heads. They have nothing to lose and easily succumb to manipulation and provocation.

In order to diffuse the acuteness of the housing problem in Ukraine, primarily among the most active population aged 40-45, mechanisms must be applied to stimulate construction. But financing from the budget and other sources and improving mortgage programmes should not lead to a galloping increase in prices. The solution requires not so much additional financial injections as organizational efforts to demonopolise the construction sector and overcome corruption.

The highly competitive construction market should be combined with access to it of foreign companies. Companies involved in the implementation of projects to build affordable housing would have to be in constant contact with a relevant government agency in order to ensure a rapid reaction to any blocking attempts by officials acting in the interests of large corporations. At the same time, criminal responsibility for bribery should be increased. It is necessary to create conditions, under which participants of the construction market would not be able to keep pointing to some hidden components of the prime cost. Otherwise state housing programmes and billions of taxpayer funds would only drive up real estate prices, as was the case in 2005-2008.

At the same time, state housing programmes for relatively prosperous citizens should be implemented jointly with developers, who will comply with clear-cut economy-class standards, particularly regarding area and auxiliary premises. Only projects that meet these criteria should be eligible for state financing. Access to relevant housing programmes must be equal for everyone, regardless of suchartificial,thus corruption-provoking and discriminatory,factors as the place of registration, being on one housing list or another, etc. There should only be one constraint – one-time participation in the programme.

However, there are citizens with income levels that are lower than those required by state housing programmes. Instead of giving them flats free of charge, which would require significant budget spending with no return, the best practice of European countries should be adopted – a model that is effective in a market economy for the provision of a category of social housing (flats and hostel rooms), that is rented out at a reduced rate and has a buy-out clause. The system is extremely flexible and has elements of self-sufficiency. For example, social housing is rented out in Great Britain, and the proceeds are immediately invested in new construction. The cycle is then repeated. In France, people who have lived in social flats for a certain period gain the right to purchase them at significantly reduced rates.

Finally, the policy of the government and the National Bank must ensure that financial risks are minimal and mortgage rates are accessible to most citizens (10-12% at most). If this were the case, budget funds would not be wasted on temporary programmes that cater to elections.

A solution to the housing problem based on European standards of area and housing quality will only be possible if overall increase in income levels driven by long-term economic growth, labour efficiency and changes in the household spending structure. Today the people of Ukraine are in essence, the poorest in Europe and spend most of their income on food. And this requires the elimination of the oligarchic-lumping model of the economy and the establishment of conditions for the realization of the potential of private initiative.

TRULY AFFORDABLE HOUSING

In early 2012, Oleksandr Rotov, First Deputy Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Builders Confederation of Ukraine, said that without the “hidden” elements, the prime cost of one square metre of housing in Kyiv in brick buildings that are up to nine storeys high, is USD 500-600 (UAH 4,000-4,800), while selling prices can start at UAH 6,000. In other words, classic affordable housing – a two-room economy-class flat, measuring 40-45 m2 – would cost UAH 240,000-270,000 at a price of UAH 6,000/m2. If a long-term (25-30 year) loan amounting to UAH 200,000-240,000 was available at an interest rate of 12-13%, monthly, the installments would not exceed UAH 2,500-3,000. This is a lot cheaper than renting a similar apartment in Kyiv (UAH 3,500-4,800 per month), which the potential buyers of affordable housing are now forced to pay anyway.

If implemented, such a project would have a large-scale multiplication effect. Among other things, rent and prices on the secondary real estate market would decline, because universally accessible programmes (for everyone except profiteers) would keep rent for economy-class flats in Kyiv below UAH 2,000, which is almost half the current level. Cumulatively, these measures could bring the price of housing on the secondary market down to USD 800-900/m2.

If as little as 3-4% of the total loan is compensated from the budget (with a maximum annual interest rate of 12-13%), the state will pay UAH 7,200-8,000 annually per flat. If one million flats are built at a cost of UAH 6,000/m2 under the “affordable housing” programme, the state will spend nearly two percent of its budget (at present – UAH 7.2 billion). At the same time, UAH 30-40 billion of private funds, which are never invested under the conditions that exist at present, will be attracted, and at least UAH 190-230 billion will come from other sources. This will lead to the relevant growth of the construction sector and thus increase deductions to the budget which could turn out to be much higher than all state expenses for the implementation of the housing programme.