Historically, this region is located very far from any centers of gravity that could have immense forces of attraction. ‘This was always a distant provincial area, whether you look at it from Kyiv, Budapest, Prague or Vienna’ – is a statement often heard with regard to transcarpathian affairs. Isolation could be seen both as a strength and weakness for this region.

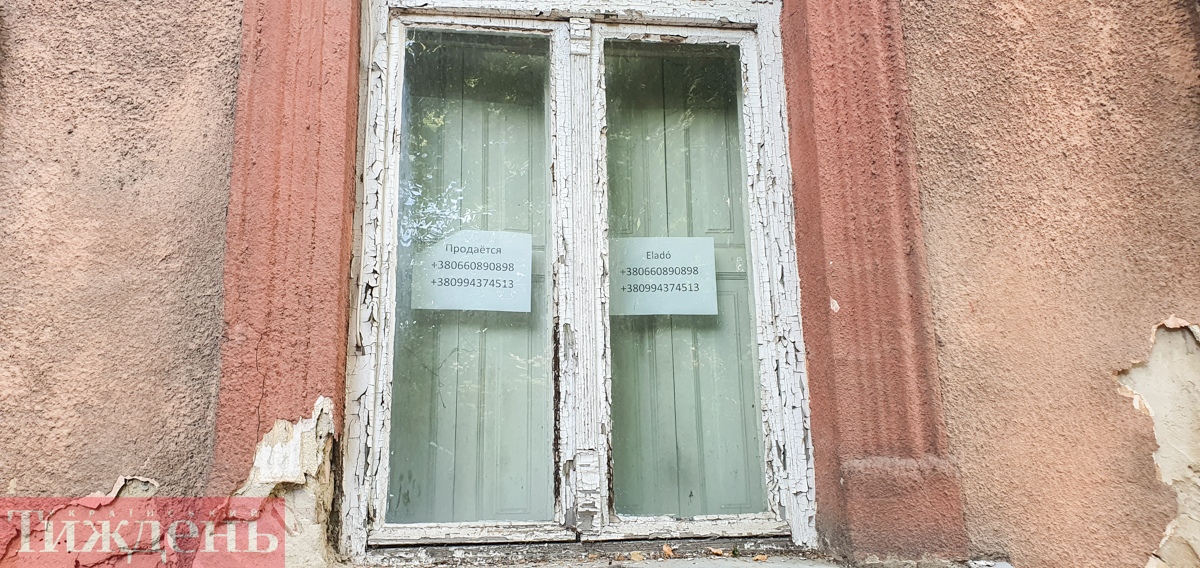

On the windows of houses in Berehove, one can often see stickers with ‘elató’ (Hungarian) written on them. Next to that, one can see a translation in Ukrainian in Russia: ‘For Sale’. Demand for housing in the local market has skyrocketed for one simple reason – war.

From the start of the Russian invasion, a large number of local Hungarian passport holders left Ukraine. For the most part (but not always), these were people from the minority-ethnic Hungarian community which populated some of these lands from way back. The Berehove administrative district is one of the few places in Ukraine where ethnic Hungarians still constitute a majority of the population. The distance to the Luzhanka border checkpoint is only 7 kilometers. Now, the inhabitants of Berehove not only leave Ukraine to wait the war out, but also intend to leave the country permanently – hence the sale of properties.

Demand for housing properties is generated by migrants from other regions of Ukraine which are present here in high numbers. By the end of May, according to the regional administration, there were already 200 businesses operating in Transcarpathia which moved from elsewhere. Berehove, along with two of the largest cities in Transcarpathia Mukacheve and Uzhhorod, is a highly demanded location. Approximately half of the relocated businesses are those of the IT sector, where income is considered to be far above the national average.

In his most recent address to the locals, the mayor of Berehove, Zoltan Babyak, said that the city has registered more than 4100 newcomers. In order to optimize the registration process and the subsequent distribution of social benefits, they are given a social benefit card by the local council. Despite this, not everyone chooses to register with the local authorities. Nevertheless, even the declared number of newcomers is over one sixth of the entire population of the town (23.4 thousand).

Transcarpathia, like the rest of Ukraine, is changing, even though one cannot hear explosions here. This region, being in the rear, is quite difficult for Russian missiles to reach: from one side you have the Carpathian mountains, and from another – NATO territory. For the duration of the big war, the region of Transcarpathia was only hit once. It happened in the east of the Carpathian mountain range.

The Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Peter Siarto has his own version of events as to why Russian missiles do not hit Transcaprathia. ‘150 thousand Hungarians live in western Ukraine. In the scenario of weapons deliveries by our side, the supply routes would become targets for the Russians. We do not want them to target the regions populated by Hungarians. We must take into account the safety of Hungary and Hungarians’ – he stated in an interview with CNN in early July.

Siarto’s statement caused an uproar in Ukraine, not for the first time. Exchanges of accusations between Budapest and Kyiv over the past five years were frequent. However, after the 24th of February, this was all the more painful for Kyiv. Siarto’s statement underlines a few issues at hand: the separation of Hungarians and Ukrainians, and the lack of will of Budapest to not only supply weapons but also transport them to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian side was quick to respond with its own staggering response. The secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, Oleksiy Danilov, in early May, stated that Hungary was not only aware of Russia’s incoming invasion but also thought that ‘it was ready to take land for itself’. After this, political tensions were somewhat able to be de-escalated: Hungary’s agreement to aid Ukraine its path to EU-integration and Ukraine’s less sharp rhetoric from then on. Behind the spotlight of such political quarrels, the situation in Transcarpathia is often left unnoticed.

After February

The Head of the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs reports rather optimistic numbers regarding the population of the Hungarian ethnic minority in Ukraine. The figure given is similar to that which was observed in a national census over 20 years ago. Even though a lot of these figures are speculative, none of the interviewees of the Ukrainian Week report numbers greater than 100,000 that live in the region at the moment. Following the start of the war, it has been often hinted that even this number is rather overestimated.

This estimation is guided both by talking with locals as well as observing the situation in the region. Natalia Myroniuk – is a representative of the Hungarian community, even though she has a very common Ukrainian name and last name. When asked about her name, she reiterates that Natalia is also a Hungarian name. She works in a local library and takes her time, excitingly, talking about her work. At the end of the excursion, she allows us to take a look at the main pride of the library’s collection: folios of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with a librarian embossing in the three common languages (at the time) in Transcarpathia: Hungarian, Slovak, and Ruthenian.

Natlia Myroniuk

These books are not given into any bystander’s hands, even though they are quite plentiful. ‘Here we have books in Ukrainian’, says Myroniuk, and then points to the next shelf and says ‘Here, we have around half of the content from Hungarian authors and further, foreign Hungarian literature in Hungarian. We have a lot of Hungarian schools and hence a lot of people who speak Hungarian’.

Bookshelf containing local authors’ works

When asked about whether such people constituted the majority here, Myroniuk said ‘Before February – yes’. Now, according to her knowledge, the situation has changed. ‘A lot of them left. A lot of people came – mostly Russian speakers. There was a moment when you would walk in town and only recognize a few familiar faces’.

Even from this discussion, one can get the sense that it’s not only the war that causes changes here. Myroniuk then says that the bulk of the library’s visitors are children and elderly people. Middle-aged people are far less common. They also have significantly less time and the majority of them moved abroad to find a better income before February 2022 anyways.

Ofcourse, it is not just Hungarians who emigrate. However, it is with the Hungarians that a rather paradoxical situation has come into place. The tendency contradicts the many statements made by Orban’s government over the past few years, aimed at the preservation of the Hungarian community in Transcarpathia.

In the very heart of Berehove, one can find the main building of the Ferenc Rakoczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian College of Higher Education. A 5-minute walk away, one can find a Roman-Catholic church. It is on the 8th of July that graduation ceremonies from the institute take place there, as students receive their diplomas. The entire event is entirely run in Hungarian. Ukrainian can only be heard a few times – when greeting guests and partner universities. The only representative of the Ukrainian government is the mayor of Berehove Zoltan Babyak, who himself is a representative of the Hungarian community. In fact, there are a few representatives of Hungarian consulates – yes, there is more than one of them in Transcarpathia. Somewhere during the middle of the ceremony, the Hungarian national anthem echoes through the walls. As per usual, similar situations cause suspicions with regard to Budapest’s strategy in Transcarpathia – moreover when a slip of the tongue leads to coverage by national TV in Ukraine.

The subsequent speech by Siladi is quite restrained. He recalls that Budapest supported Ukraine in its plight for obtaining EU candidate status and reiterates his will of Ukraine being a ‘sovereign, balanced, democratic and law-bound state, where ethnic minorities, including the Hungarians, can live in their fatherland in peace’. This is achievable after the establishment of peace as Hungary Ukraine ‘within reason’. He then recalls the need for ‘the restoration of the rights of the Hungarian ethnic minority in Transcarpathia’, but after the war and using a method ‘that is satisfactory to both sides’.

His speech also contained a rather different part. Siladi continues to talk about the century-long struggle of the Hungarians of Transcarpathia, which forced the community to fight for its survival. In the end the struggle was successful and ‘thanks to the support of the Hungarian government’, further development has been facilitated, especially after the introduction of the so-called new national policies from 2010. It was in 2010 that Viktor Orban came back to power and remains so today.

‘The century-long struggle’ is not merely a tool of rhetoric as it may seem at first. It is about a specific reference to a historical event, which is never omitted from any speech in the Hungarian community in Transcarpathia, as well as Hungarian politics in general. The recollection of events usually unravels as such: on the 4th of June, 1920, near Paris, the Treaty of Trianon is signed between Hungary and the countries of the Entente, which established new borders after the First World War. Given that Hungary lost the war, nothing good from such a treaty would ever come. The country lost two thirds of its ethnic territories. This became a national tragedy, and even a key component of the political process of modern Hungary. These events were a crucial internal political phenomena that still play a key role for Hungarians living abroad.

‘Uniting the Hungarian people within the borders of one state is impossible, but it is important to unify Hungarians mentally and culturally, in order to preserve our values’ – laconically states his ideas Dmytro Tuzhanskyi, the director of The Institute for Central European Strategy, a center for analytics based in Uzhhorod. He emphasizes that this rhetoric is the basis of all political discourse in Hungarian political circles. Tuzhanskyi states that this is the right context for seeing and conceiving the Hungarian ethnic autonomy, which was often led by the government in Budapest itself.

Ukrainians have their own traumatic historical associations with the word ‘autonomy’. It is associated with the long-standing Russian attempts to divide the nation from within in order to take over territory. The main propagator of the federalization of Ukraine was Viktor Medvedchuk, Putin’s key political ally in Kyiv. Now, this association is augmented by the war. The war hence does not add any trust or understanding to the belligerents of the stand-off in Transcarpathia.

Dmytro Tuzhanskyi

The Hungarian institute Berehove, which awards its diplomas in the nearby catholic church in the presence of Budapest officials, is not a strange occurrence from the perspective of the Hungarians. For them, this is the symbol of their ethnic autonomy, which has to reach all domains of their life. Another example could be the Kárpátaljai Magyar Kulturális Szövetség (KMKS) – all being a Hungarian cultural organization, political party and a charitable fund. For many Ukrainians, this raises suspicion: Russian expansionism also started from the combination of politics, culture, religion and money.

As soon as the official ceremony in the church is over, Berehove starts to resemble a regular town on graduation day. The girls do not hold back on their makeup, ‘white top, black bottom’ for boys, a lot of bouquets – and all of this holds to all age categories. Freshly graduated students, along with their parents, start to disperse. At the moment, it is difficult to estimate how many of them will pursue their careers in their hometown.

The entirety of the Hungarian education system in Transcarpathia – starting from kindergarten all the way up to universities, became the main reason as to the difficult relations between Ukraine and Hungary. From the perspective of many Hungarians, Ukraine’s education bill introduced in 2017 violates the rights of the Hungarian ethnic community. The bill entails the gradual switch to Ukrainian for most subjects in school. The alternative view here argues that it is the very fact that the Hungarian education system here was the reason as to why so many ethnic Hungarians were leaving.

Paint and Flags

Across the road from the catholic church, one can find another local landmark: the palace of Count István Bethlen, which has been converted into a local history museum. In a nearby structure, one can find one of the local volunteer centers providing aid. Next to the entrance, a red-black flag is seen waving, which in Berehove instantly stands out in contrast to the numerous Hungarian flags on display.

During the visit to the center, the person in charge was Tetyana Vovkunovych, as it could be taken note that the center was rather disorderly at that moment. Children were playing ping-pong and running around in the yard non-stop, while further on, someone arranged a relaxation zone with bean bags. The zone does not really fit the environment but nevertheless, looks very cozy. Nearby, there is also a place where torn-down communist monuments and symbols are stored. As became clear later on, the basement of the palace has been converted into a bomb shelter, with an improvised cinema and theater hall. Even though the interior of the palace does not come across as a unitary conception, it still gives the impression of a united and pulsating organism.

Bomb shelter in the palace

– Greetings. Where have you come from?

– Hello. From Lyman (a city in the Donetsk region, occupied by the Russian army in late-May).

– Ohh. So you will be staying here for a while…

The dialogue is held between Vovkunovych and a young woman with a child, who is trying to figure out her housing situation in her new place. Vovkunovych tells us that the center here started to operate after Russia’s invasion in February, at which point volunteers were allowed to use public buildings. Betlen’s palace, sometimes called ‘the oldest building in Berehove’ and other old relics in town are fairly easy to find. The palace itself is overdue for repairs and the volunteers themselves have started to fix the roof.

Decommunised symbols/monuments

This contrasts the rest of the city, which often resembles a museum under open air. One can see many statues of Hungarian historical figures around the place, covered with wreaths containing ribbons with Hungarian flag colors. Buildings that belong to Hungarian cultural communities are for the most part, well looked after – for example, the cultural center where a prominent Ukrainian-based Hungarian theater would perform. The issue here is that the hall is closed and no theatrical performances take place anymore.

The statue of Francis II Rákóczi in Berehove, the leader of the Hungarian national liberation movement in the 18th century

Well looked after cultural centers with Hungarian flags on display is another controversial matter. Budapest, with its system of financial grants, provides the Hungarians with financial aid at the individual level – teachers, doctors, parents of Hungarian schoolchildren, farmers, business owners as well as funds for the reconstruction and repairs for civilian infrastructure. The very same institute of Ferenc Rakoczi II looked as if it was on the frontline of a war. Now, it looks like a flawless and phenomenal building. In a similar manner, the former Austro-Hungarian bank building was refurbished in Mukacheve and was converted into a Hungarian cultural center. The Hungarian flag is always hung up afterwards.

– It is useful for everyone, but there’s an issue with the politicization of this matter, says Dmytro Tuzhanskyi. According to him, there was always a concern that the region had lost interest of the government in Kyiv and would have been bankrupt without the money coming in. This, however, is manipulation. Basic funds from the government are received by the Hungarian schools as well. As a result, this reminds one of ribbon cutting ceremonies that candidates resort to in their districts before elections, even though the ribbon envils something that is state funded and has nothing to do with them.

School with Ukrainian and Hungarian flags on its facade

As an example, according to the data of Ukrainian officials, Ukraine spent 160 million EUR on roads in the region in 2020 alone. Hungary reports to have spent a few hundred million Euros in the region through different funds, but as a total from 2010.

The ‘Big Hungarian construction’, which is often seen decorated with flags and other signs of Budapest’s presence here, causes anxiety from the ethnic Ukrainian population. In fact, in the past, the city may even penalize those who display the red-black flag as it is associated only with Ukrainian nationalists. Now, this flag is a symbol of resistance against Russian aggression.

– When the war began, we hung up a bunch of Ukrainian flags here on the bridge, as you might have noticed. There was an idea to hang one red-black flag for every yellow-blue one. The guys were taken by the police and were told ‘Do not hang those, don’t antagonize the Hungarians’. ‘And I tell them – don’t worry, we will hang them up on independence day anyways’ – says Tetyana Vovkunovych.

This story is supported by the available materials from the court registry of a case labeled as ‘petty hooliganism’. There were actually two proceedings from the initial engagement. The story happened on the 9th of March, at the very early stage of the big war. ‘Being on the Petefi street in Berehove he swapped the Ukrainian national flag to the red-black flag, and then hung the Ukrainian national flag next to it. The actions of the person in question took place in a public place, in the eyes of bystander citizens’ – is stated in the text from the verdict of one of the proceedings. The court returned the verdict to the police through improper registration. The second person involved was given a fine of 51 UAH and an additional 500 UAH court fee.

‘One must live here to truly understand’

When talks of risks of Hungarian separatism in Transcarpathia and alleged plans of Budapest to take advantage of the prospect of Kyiv’s early fall following the invasion in February arise, the interviewees only smirk. They do however think if Hungary was to show up, a certain amount of people would be satisfied with such a turn of events. The overall attitude among the people is described as ‘it is hard to explain, one must live here in order to understand’. Although, the interviewees are more keen to speak about this topic when the microphones are off.

– Talks of unification of this part of Transcarpathia with Hungary can be heard on a daily basis from those who are often called as ‘armchair experts’. Such people are from the countryside, they are unhappy with their lives. And they are not only Hungarians. It is those who live in an isolated or remote environment. There is no such thing that it is en masse, that it is a key idea, aim, or desire – says Dmytro Tuzhanskyi.

One of the more direct collocutors talking with us was Tetyana Vovkunovych, but even from her words, one can understand that soon, there would be no one to label as a seperatist in Transcarpathia:

– If I was the central government, I would close these [Hungarian] schools and introduce a sunday school. As it stands, Ukraine is preparing specialists for Hungary. They don’t know a single word of Ukrainian. What next? They make diploma duplicates and head for Hungary.

This expression holds a hidden message, which is also promoted by the central government in Kyiv, although a little more softly. The notion is based on the fact that Hungary itself pushes ethnic Hungarians to leave Ukraine. Without knowing the language, they are unable to pursue their desired professions in Ukraine. It could be said that the future here is more powerful than the past with its ‘good-looking statues’ (i.e. repairs made for Hungarian centers). A second problem which has long been outlined, the lack of Ukrainian speaking skills, which is very common in Hungarian villages, separates the community from the rest of the Ukraine politically. Hence, the Hungarian community ends up in self-isolation, while raising suspicions from Ukrainians. After the Russian invasion, Hungarian leaders started to avoid these sensitive issues even more. For example, the Ukrainian Week tried to reach Laslo Zubanych, one of the leaders of a Hungarian political party in Transcarpathia – the Democratic Union of Hungarians of Ukraine, but after three attempted calls and a text message, he did not reply.

Maria Zhylenko offers excursions in the Archeological Museum of the University of Uzhhorod. She is originally from a Hungarian village in Transcarpathia, even though she emphasizes that she is from a mixed family and was also raised by her grandmother who was Ukrainian: ‘I am not really a typical Hungarian, I am in a mixed marriage and family. Perhaps 100% Hungarians will be able to tell you more’.

However, the discussion that ensued gave us a possibility to encapsulate life in the community at least a bit. According to Maria, the local Hungarian population watches Hungarian TV, lives in the Hungarian timezone, and is fully oriented towards Hungary. However, this isn’t something new. This was already the case during the Soviet era. Zhylenko tells us that she herself lived under such circumstances. The only difference back then was that all men knew Russian at the time, as serving in the army was a necessity. ‘This isn’t a current ongoing policy, this has developed beforehand, traditionally’ – she says. Zhylenko herself learned basic Ukrainian thanks to her grandmother, but then became fluent in literary Ukrainian in university, even though it may seem hard to believe at the moment. When asked about what Ukraine can do to improve the integration of the Hungarian minority, she replies:

– The Hungarian community does not really wish to integrate, so doing it by force would be wrong. They do not know the official language, and hence, cannot get admitted to any prominent Ukrainian universities and pursue a decent job. In other words, they mingle with their own. They are enclosed, so to say. There was one good example. A fund once requested for a church to be refurbished. It was a Hungarian village, and we met the head of the local community associated with the church. He complained about how things were going. His daughter was lucky, she had a good job, she became the director of a school in a neighboring village. His son though, was poor, is not being taken for work anywhere, and has to work on his father’s farm. As we figured, his daughter knew Ukrainian but his son didn’t.

Maria Zhylenko

She further adds that after the formation of separate Hungarian faculties and colleges, they started to resemble ghettos. As a result, young people who wish to develop themselves, have no option but to leave for Hungary. In Hungary, a new beginning awaits them, however, the Hungarian government’s depiction does not always exactly match reality, and the locals in Hungary may treat them as Ukrainians who are competing for their income: ‘Hungarians perceive it as sort of a sledgehammer – “Trianon, they took away the land.” There is a similar concern when it comes to the distribution of pensions. Suddenly, the patriotism disappears’

Natalia Myroniuk, from the Berehove library denies the existence of any problems: ‘Perhaps people in remote villages, who do not see anything besides their cattle and do not know any Ukrainian. This is not common, however. It may be the case that people simply do not want to speak, so for them it is easy just to pretend that they don’t know Ukrainian’. She also does not agree with the notion that the Hungarian community is separate from the rest of society. ‘We are very open. We organize a lot of food festivals, wine and cultural events. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, everything stopped. And now, how can we drink wine and reopen everything knowing that our guys are dying on the frontline?’.

As for the view of the war, many in Transcarpathia emphasize that one should not confuse the tensions between Kyiv and Budapest and the attitudes of the Hungarian community in Transcarpathia regarding the war. In fact, there are numerous examples of ethnic Hungarians which are currently on the frontlines, as well as civilians, providing aid.

– A guy from Hungary donated a washing machine as well as 10,000$. I asked him ‘Are you one of the Orbanites, or not? He said no, he is one of those who are against Orban, one of the ‘conscious’ ones so to say. He came and distributed the funds among the different volunteer organizations and we received 1,200$. There are also some of our own, locals, Hungarians that provide a lot of help, those who love Ukraine and have strong associations with it. Those who do not, were rather restrained – says Tetyana Vovkunovych, from a volunteer center in Berehove.

The last interviewee of the Ukrainian Week in Transcarpathia was Dmytro Korbynskyi. Being a native of Kyiv, who sold his property in Kyiv 12 years ago and moved to Berehove and bought a house there – a house that was built in the first half of the 20th century, when the region was under the control of Czechoslovakia. From then on, Korbynskyi has been repairing and refurbishing it and became rather a well known personality among the locals due to the style which he chose for the building. One of the local papers has even labeled the house as a ‘fairytale house’.

– One cannot look at Transcarpathia as a regular Ukrainian region, – says Korbynskyi. – The problems and the long-standing traditions of the locals, which date back centuries, should not be disregarded. As for the language bill, I was on the Hungarians’ side, it is just simply wrong to force them to do so. They say that their education has been in Hungarian since the days of the Austro-Hungarian empire, during the Czechoslovak and Soviet rule as well, but now it is different? I want them to learn Ukrainian and it would make sense for them to take the relevant exams, but one cannot see it as straightforward as that. Perhaps, they should be taught more of a Ukrainian-vision of things in Hungarian. Conditions must be made, – he says.

Dmytro Korbynskyi.

One of the long-standing traditions of the region became the relative ease with which the region receives newcomers. The cultural diversity here helps with that. With this in mind, it can be said that Transcarpathia is more ready to adapt to wartime than many other regions in Ukraine. For this, it is important for Ukraine to preserve its own.