The major TV channel in Ukraine had retransmitted content from Ostankino, Russia’s public broadcaster, up until 1996 when Inter, a private TV channel infamous for pro-Russian sentiments, took over. The post-colonial tradition did not evolved uninterrupted in Ukraine’s media space since the soviet time. In the 1990s, Ukraine had media that were fairly resilient to any Russian influences.

Private broadcasters of the independent Ukraine, such as 1+1 channel, shaped a generation of celebrity journalists who spoke Ukrainian on air, did not work under the management of Moscow expats and have  become household names. Radio Lux played good quality music from Ukraine and around the world without focusing almost entirely on low quality Russian pop music. Dubbed into Ukrainian and screened at ICTV, Alf remains a legendary TV series. Ukrainian products were offered in other niches, from an MTV-like pop music shows like Terytoria A to erotic magazines like Lel or Mister + Miss. Regardless of their aesthetics, the fact was that Ukraine had its information independence with a focus on itself. The likes of Inter with their cheesy New Year concerts broadcasted from Russia did not have a decisive presence or influence in it.

become household names. Radio Lux played good quality music from Ukraine and around the world without focusing almost entirely on low quality Russian pop music. Dubbed into Ukrainian and screened at ICTV, Alf remains a legendary TV series. Ukrainian products were offered in other niches, from an MTV-like pop music shows like Terytoria A to erotic magazines like Lel or Mister + Miss. Regardless of their aesthetics, the fact was that Ukraine had its information independence with a focus on itself. The likes of Inter with their cheesy New Year concerts broadcasted from Russia did not have a decisive presence or influence in it.

Russia’s new information invasion began in the 2000s with oligarchs entering the scene as the owners of the biggest media holdings in Ukraine and foreign investment coming into the media market from Russia primarily. The process looked like a distorted version of colonial globalization. This environment cultivated a message portraying Ukraine’s media market as outdated and underdeveloped, and professional expats were seen as its only chance for transformation. The Russians seemed to naturally fit into the role of these expats as representatives of the region’s metropolis. It was then that a number of myths were born: “nobody will buy your content in Ukrainian”, “nobody reads in Ukrainian”, “Ukrainian is for the countryside and Western Ukraine”, “business doesn’t speak Ukrainian.”

RELATED ARTICLE: One-sided bans. Why are Ukrainian users more and more often finding themselves banned by Facebook?

While Ukrainian journalists vehemently opposed the temnyks, the unofficial instructions with messages for the media, in the era of Leonid Kuchma’s presidency, they failed to respond to these colonial messages. When the branch of Kommersant, a Russian business magazine, opened up in Ukraine, journalists hailed the arrival of a professional business media with decent salaries. That’s how the professional crowd perceived the opening of Russia’s No1 business newspaper in Ukraine. More smaller outlets, including Expert or Profile, followed suit.

The new generation of journalists from the 2010s barely remembers these brands today. Back in the day, however, each of these outlets saw itself as a civilizer that was bringing high Russian standards to the aboriginals.

As Vladimir Putin gradually cracked down on media freedom in Russia, more and more experts, consultants, spin doctors, media managers and journalists moved to Ukraine. Paradoxically, they were leaving a country where democratic elections and freedom of speech had been long gone and moving to Ukraine to preach their “success stories”. Surprisingly, Ukrainian political and business establishments embraced these white émigrés as top professionals capable of triggering the development of their own projects.

It is unacceptably chauvinistic to accuse people of anything based on his or her country of origin. The problem, however, was that many Russian journalists and media managers blended their declared liberal and democratic values with promoting the standards of common information space for Russia and Ukraine. Talk shows after the Orange Revolution often had guests like notorious Russian politicians Vladimir Zhyrinovski or Konstantin Zatulin. Svoboda’s Andriy Illenko battled on air with Nikita Mikhalkov, Russian film director and a fan of Vladimir Putin. Russian guests used prime time air in Ukraine to voice all their messages and get access to the multimillion audience. That format was not dictated by anyone to the media bosses. They filled Ukraine’s media space with Russian celebrity guests because they thought that Ukrainian television needed that.

RELATED ARTICLE: Studio sleight of hand. How Ukraine’s talk shows work

It is fair to say that the residents of Crimea and parts of the Donbas lost their loyalty to Ukraine while watching Russian television. It is equally fair to say that most Ukrainian TV channels had conveniently integrated into the common information space with Russia. Broadcasting within that space did not help their audience develop antidotes to the Kremlin’s influence.

Political talk shows were not the only culprits. In the early 2000s, a sort of “little Russian vaudevilles” became trendy in Ukraine. These were New Year musical films coproduced with the Russians. They featured the likes of Oleh Skrypka, a headliner of Ukrainian rock music, alongside the likes of Philip Kirkorov, Russia’s king of pop. When talent shows became trendier later, the jury always included at least one guest start from Russia. This looked like any trivial post-colonial situation where the country just didn’t feel right without the cultural context of its former empire. The infamous Kivalov-Kolesnichenko language law that discriminated the position of the Ukrainian language was passed in 2012, but information preparation for it had started way before. It proved quite successful, too. Even the generation born after 1991 consistently fit into the Russian cultural context, from pop music to fashion magazines and business press. Young Ukrainians studied in Ukrainian schools and universities in an environment where Ukrainian was often seen as a language of official documents and procedures while all truly successful people were actually Russian-speakers. The media played the key role in the construction of this myth.

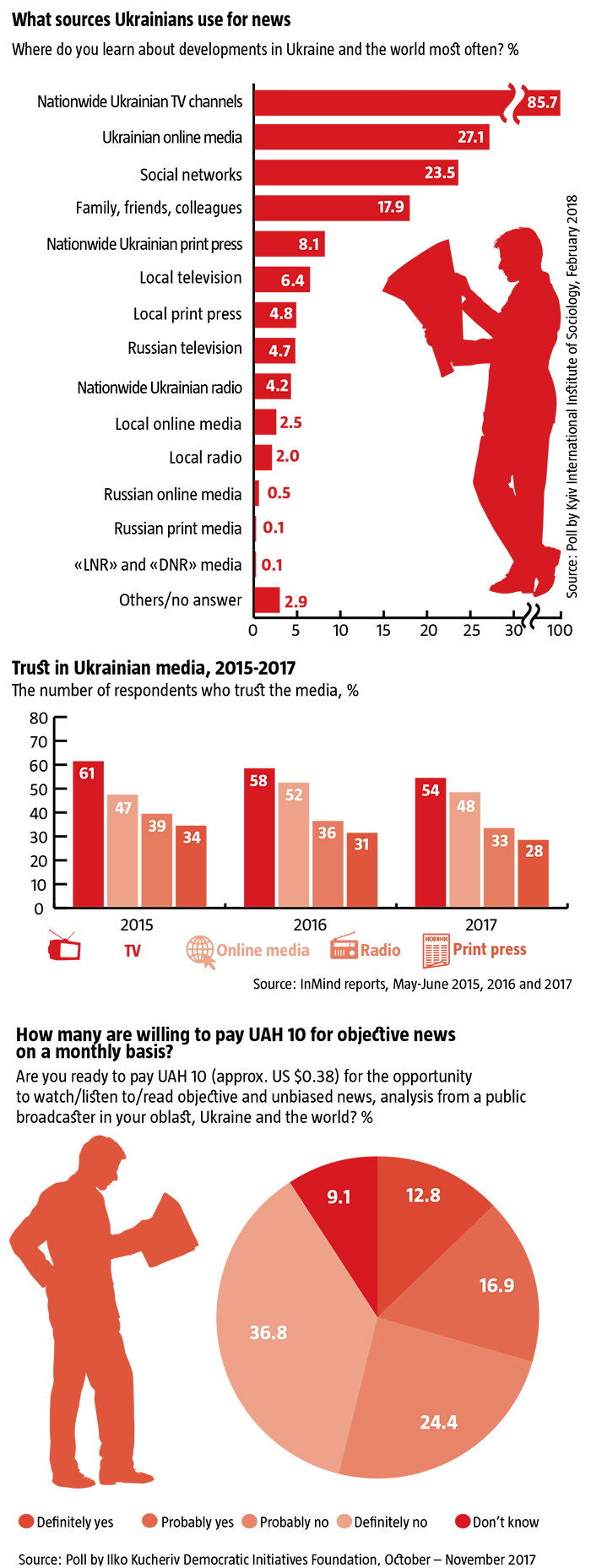

Polls, such as a recent one by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology revealing that 37% of Ukrainians perceive Russia positively, cause waves of popular frustration. Many of these respondents were probably not affected by the Maidan and tend to be naturally passive or indifferent as citizens, spending a lot of time watching TV. While they will quickly forget a brief appearance of a military press secretary reporting on the frequency of shelling or number of victims, the common cultural context shaped over the years is far harder to shed.

It would be wrong to claim that Ukrainian media community has learned its past mistakes and decolonized its information space. It does have a new playing field and rules. But white émigrés are still trendy. Many Russian liberals in Ukraine seem to be less willing to assimilate here and more willing to use Ukraine as a platform for building “a different Russia”. Journalists still tend to use Russian media as a source of international news. A journalist from a top online outlet mentioned the Russian Meduza online outlet as an example to follow at a recent media forum. “They are gods” was her comment. Such faith will hardly help Ukrainians disentangle from the web of Russkiy Mir. Recipes for treating such chronic diseases lie inside, not outside. It is wrong to blame Ukraine’s government, however flawed, for this. The solution lies in medice cura te ipsum – Physician, heal thyself!

One other professional disease stands in the way: many in Ukrainian journalism are unable to recognize their own mistakes, say that they were wrong and apologize. Just like politicians, they prefer to count on the short memory span of their co-citizens. Still, they also have good situational awareness. Hopefully, they won’t rush to construct a common information space with Russia ever again.

Infographics by Maksym Vikhrov

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook