Labor migration from Ukraine has changed cardinally in recent years and differs from previous waves both by its very nature and by its impact on the economic situation in the country. The massive scale of this new migration is only starting to be felt and it’s becoming obvious that, without the necessary rethink and adjustments to economic, tax and social policy, it will eventually threaten huge problem and imbalances.

Ukrainian migrant workers in the 1990s and early 2000s were much more driven than today by the need to simply survive for individuals who had lost their means of living during the transition period back home. Migrant flows went mostly to more distant countries in Western Europe and the vast majority of these illegals rarely came home before they managed to gain some form of official status in their new country of residence. Today’s migrant workers are mostly going officially, with more noticeable fluctuating and seasonal components, looking ever more like a natural extension of migrant flows within Ukraine itself, as individuals from depressed regions, rural areas and suburbs continue to move to larger and wealthier economic centers.

By comparison, the scale of migration across the border is not as big, but the potential for it to grow remains fairly high. Derzhstat figures show that, since 2012 alone, some 450-650,000 Ukrainians change their domicile within the country annually, for a variety of reasons, but mainly economic ones. An even larger number do so unofficially or are part of the fluctuating and seasonal migration from population centers where they reside to those where they find a job. While this internal migration of Ukrainians is not as noticeable as the cross-border version, its impact on the socio-economic situation and tax revenues not much less vital.

Lately, these internal movements between bedroom and employment communities and places in the middle of the countries have simply overflowed beyond it. Moreover, this is not just as the result of some critical worsening of the economic situation in Ukraine, as is popular to state these days, but mainly because of the liberalized visa regime and the improvement of opportunities to be officially employed in EU countries neighboring Ukraine that have a labor shortage. This was the natural outcome of the process of bringing Ukraine into a unified European economic and human space at the same time as the domestic labor market remained uncompetitive.

Not by Poland alone

The first and so far most powerful magnet for Ukrainians was the biggest neighboring EU economy, Poland. In 2017 alone, Warsaw issued new residency permits to over 585,000 Ukrainian citizens, while in QIII of 2018, the number of Ukrainians working there legally had grown to 426,000 according to the Polish Social Insurance Fund. However, the Polish labor market has lost some of its attractiveness for Ukraine’s migrant workers lately. The NBU prepared an analytical brief that registered a slowdown in the pace of issuing new permits, which suggests that the flow of Ukrainian migrants to Poland will slow down in 2019 and further. The number of applications for employment was already down in the first six months of the year to the level of the first half-year in 2016.

RELATED ARTICLE: Slaloming the risks

Having tested the waters in Poland, Ukrainians have more actively been checking out labor markets in other, so far mostly post-socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, where access to jobs has become much easier. Indeed, Ukrainians are the top group gaining residency or work permits in Lithuania, Estonia, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary. More recently, they joined the top three immigration group in Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, and Denmark. For instance, in 2016, the official Czech quota for workers from Ukraine was only 3,800, but it has grown more than tenfold, doubling every year: to 7,200 in 2017, 19,600 in 2018 and 40,000 for 2019 according to a recent decision by the Czech Government. Lithuania issued 18,000 working visas in 2016, of which nearly 10,000 went to Ukrainians, while in 2017, 20,000 Ukrainians received them and in 2018 19,000 permits were issued to Ukrainians in just the first seven months. Estonia, which is less than half the size, issued 12,000 permits to Ukrainians in the first three quarters of 2018, amounting to nearly 1% of the country’s entire, not just able-bodied, population. Among Baltic countries, the smallest number of Ukrainians goes to Latvia, which issued around 3,000 work permits. However, the growing trend of migration to other CEE countries could well bring the number of Ukrainians in Latvia up to the tens of thousands.

Next stop Germany

A dramatic increase in access to the relatively small countries in CEE could prove to have been just a prelude to a massive entrance to the largest economy in the European Union, with one of the highest salary levels on the continent, Germany. At the moment, Ukrainian migrant workers are a relatively small group there: official statistics put the number officially employed there at around 43,000, up 10% for 2018. These numbers are in the same ballpark as Czechia, Lithuania or Estonia, with their many times smaller populations, economies and wages.

However, the situation is about to change radically as Berlin has decided to liberalize access to the labor market for countries that are not EU members, just as it did for its eastern neighbors earlier. The new rules allow citizens of a non-EU country to easily get a six-month work permit. They will be able to not just to fill new vacancies but also compete with migrant workers from neighboring EU countries. Today, Germany reports over 420,000 officially registered employees from Poland and 350,000 from Romania. Predictions are that quite a few Ukrainian migrant workers will move from Poland to Germany. It’s quite likely that Ukrainians working in Czechia, Lithuania and Estonia will also begin to shift westwards, which will increase demand – and wages – on those labor markets to attract more Ukrainians, as they remain the largest and least expensive labor force among all other European countries.

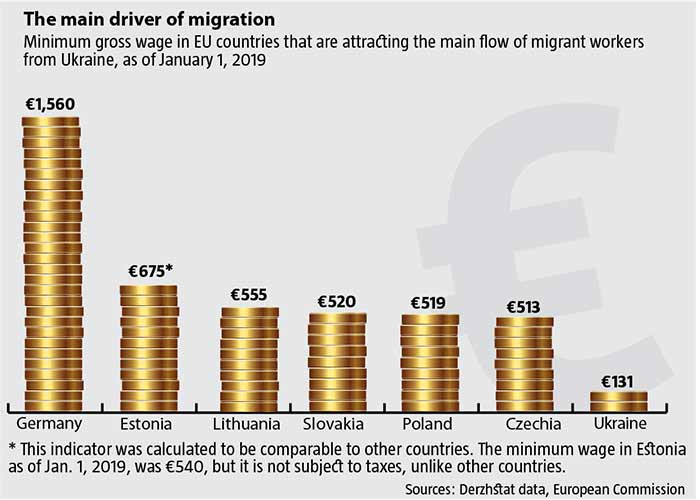

All these changes will spur an even larger outflow of new workers from Ukraine, as the difference in wages remains extremely high. For instance, based on available data, even the minimum wage in Poland has gone up to PLN 2,250 as of Jan. 1, 2019, or nearly UAH 16.400 at the current exchange rate, in Czechia it is CZK 13,350 or around UAH 16,300, and in Slovakia it’s €520, which is also close to the Polish level. In Lithuania, the minimum wage is now up to an even higher €555 or about UAH 17,500, in Estonia it’s €540, but this level of income is not taxed in Estonia, so in fact, it is the range of about €675 or UAH 21,300 at the current exchange rate compared to the other countries, all of whom tax this level of income. Meanwhile, the gross minimum wage in Ukraine has just gone up to nearly UAH 4,200, but in fact even the average wage in most parts of the country is well below than the minimum in neighboring EU countries.

Unquestionably, such an enormous difference in the value of labor has been drawing Ukrainians away from the domestic labor market and will continue to draw them to neighboring countries, not only on a permanent basis but also on a seasonal and fluctuating basis.

Those who stay behind

What’s more, in Ukraine itself, competition is growing for those workers who are in demand on other European markets. This is forcing wages up, a trend that should continue, and leading to inter-sectoral flows, especially from those branches and professions that were traditionally considered more qualified and complicated to simpler work, including manual labor. The extremely low salary levels in the government sector and public services, and in a slew of other sectors of the economy from which direct migration to the EU is not possible is forcing some part of those employed there to retrain and replace workers in fields Ukrainians are most actively leaving behind for the EU.

Meanwhile, this group is actively expanding thanks to those spheres where the European labor market was difficult to access or closed altogether until not long ago. Among others, in spring 2018, the Polish Health Ministry turned to Ukraine’s Ministry of Education and Science with a proposal to simplify the recognition of medical diplomas for those who gained them abroad. One of the main requirements was knowing the Polish language. Today, Poland is expecting a huge shortage of mid-level medical personal: of 220,000 nurses that are employed in that country, 73,000 are already of retirement age, while there are less than half as many doctors per 1,000 residents than the average for the EU. It’s obvious how this shortage will be covered: even given the existing barriers to this particular segment of the labor market, Ukrainians already constitute 36% of the foreigners who have the right to practice medicine in Poland.

If current trends continue, the difference in wages, compounded by the structural problems in Ukraine’s economy and the lack of proper government policy to modernize and expand industrialization, inertia will transform Ukraine into one huge bedroom community for the wealthier countries of the EU. This process will pick up pace, deepening the shortage of labor in many segments of Ukraine’s economy while increasing demand for goods and services on the part of the families of migrants and, depending on the season, the workers themselves.

These new realities will lead to changes in attitudes towards the problem of migrant labor and the position of migrant workers both in their communities and in relation to the government. They are getting rid of the label, “the most impoverished segment of Ukrainian society, which has to save itself from starvation because it could not find a job at home.” More and more, migrant workers from Ukraine are looking for higher salaries, not going for a job that they could just as easily have in Ukraine, but for much smaller pay.

Meanwhile, the burden of supporting the social sphere and infrastructure in Ukraine is borne by those who continue to work in their homeland for a much smaller wage. Aligning Ukraine’s prices and rates with world levels and raising rates of pay for the work of specialists in areas from which they are going abroad to European levels need to be extended to include raising the pay of those who stay behind in the other domestic spheres.

RELATED ARTICLE: Potential or lost souls?

In a situation where Ukraine is turning more and more to an EU suburb for migrant commuters, taxation systems also cannot stay the way they were in the past, as they were based on a post-soviet social model. This situation needs a mechanism to radically rebalance taxation and social contributions, the financing of education and medicine, and expanding the system to include contributions from migrant workers. Either that, or these spheres will start to degrade severely over time, with a growing shortage of resources to fund them, and worsening fiscal and quasi-fiscal pressure on those who continue to live and work in Ukraine. And this inevitably means that their real standard of living will decline.

The current model of centralized funding of such services as healthcare, education and welfare, which are enshrined in Ukraine’s Constitution, simply does not anticipate a situation where a growing segment of the able-bodied population will be making their livings outside the domestic economy. The question of how to get those who work abroad to contribute to the ever-growing burden of budget and social fund funding back home is about to become a major problem.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook