The Iraq War is arguably among the most significant international events of the past decade, impacting the diplomatic landscape not only in the Middle East but the entire world. It involved multibillion-dollar defence spending that weakened the US economy, civilian casualties, and prisoner abuse scandals (including Abu Ghraib). The military campaign a decade ago had an impact on the lives of 30 million Iraqis, many of them initially welcoming the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, one of the most powerful contemporary authoritarian leaders.

Today, there is no shooting or kidnapping on the streets of the Iraqi capital. If it weren’t for the military checkpoints every hundred metres and the fortified Green Zone in the downtown area that encircles government buildings and embassies, life in the city of seven million would appear common, almost vibrant.

Yet, people are still killed today. Mohhamed Liami, 28, was preparing for his upcoming wedding when he was killed in a car bomb explosion at a market. His brother says that the family received no compensation at all. Such episodes are common in Baghdad.

However, neither security guards – a must for local politicians who are a primary terrorist target – nor the military, ubiquitous in the downtown area yet barely present in poorer districts, can safeguard average Iraqis from a terrorist attack. Meanwhile, the Iraqis have developed their own identification system: if a bomb is planted somewhere, the pro-Hussein Ba’athists are to blame; if a suicide bomber attacks, Al-Qaeda is the culprit.

LIBERATION OR OCCUPATION?

“Killings in terrorist attacks are very tricky. We’ve often seen family and friends rushing to help the injured, and the second bomb would go off,” sighs Abu Fatma, Mohhamed’s uncle. “Over these years, around sixty people have been killed in my block alone which is home to a thousand families. They were all neighbours whom I knew personally.” Abu Fatma’s unpretentious two-room home with a dovecote in the backyard sits in Sadr City – formerly Saddam City – one of the most populated districts. This Baghdad suburb is considered to be the outpost of Muqtadā al-Sadr, a radical Shia leader. From 2005 through 2008, it had been the heart of an exhaustive fight against US troops and the Iraqi Army. White-haired Abu Fatma claims that Sadr City has its ill fame only because it was inhabited by the oppressed poor both under Saddam and now. “Good people live here. I could easily walk you around in the middle of the night,” he comments. “Most of us are Shia Muslims, but Sunni families live next to us. The problems are between politicians, and because of Al-Qaeda for which no one is innocent.” Abu Fatma’s family lives on USD $320 a month – the pensions of two 1980-1988 Persian Gulf War veterans in the family. They say it’s enough and do not expect more government support. “Back then, in 2003, we did welcome the Americans, looking forward to liberation from Saddam who oppressed the Shias. But the way the occupational government treated civilians was unexpected. So was the fact that the Iraqi government began to work for personal enrichment rather than for the people. Everyone betrayed us.”

READ ALSO: Iraq: Turning into an Authoritarian State

Virtually all of the Iraqis I met – whether the poor inhabitants of Sadr City or the Sunni in Al Anbar Governorate where anti-discrimination protests have been going on for three months now, or progressive young people or politicians – seem to miss the Saddam Hussein era. Still, regardless of their social status, religion or ethnic origin, they say the overthrow of the regime and the beginning of the campaign were very different from the later actions of the U.S. military.

“Any occupation is unacceptable. We agreed to help from coalition forces, but then everything went wrong. The UN Security Council legitimized the US action in Iraq, and liberators turned into occupiers,” says Labid Abbawi, Chief Advisor and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Iraq. “Paul Bremer, the chief executive of the American occupational administration, did not know the region and set rules that provoked a slew of problems. The army and security service were disbanded. Hundreds of thousands of armed men ended up in the streets jobless. The process of removing mostly Sunni members of Ba’ath, the only party under Saddam, from the public domain ran counter to the idea of national reconciliation. Forced principles of governance have deepened and reinforced ethnic division. Unsurprisingly, people turned away from America,” he says.

READ ALSO: Former Enemies Find Common Ground on Kurdish Rebels

“I was 13 years old when the assault began,” recalls Ali, a 23-year old Iraqi Culture Ministry employee. “As a teenager, I thought that Baghdad would turn into Los Angeles once Saddam was ousted. What did I know about the US? We had no cell phones, or Internet, or satellite TV. It was fun at first: we practiced our English with US troops, played football and chess with them. But everything changed after the Americans blew up the first civilian car. They started to behave like masters after Saddam was captured. The insult was painful.”

CHILDHOOD IN BAGHDAD

Ali is working on a project to transform Baghdad from a city where armoured vehicles are often stuck in traffic jams alongside taxis into the region's cultural capital. “The war has made people forget what culture is,” he explains. “We will lose one more generation unless we start reviving it now. We must return to normal life.”

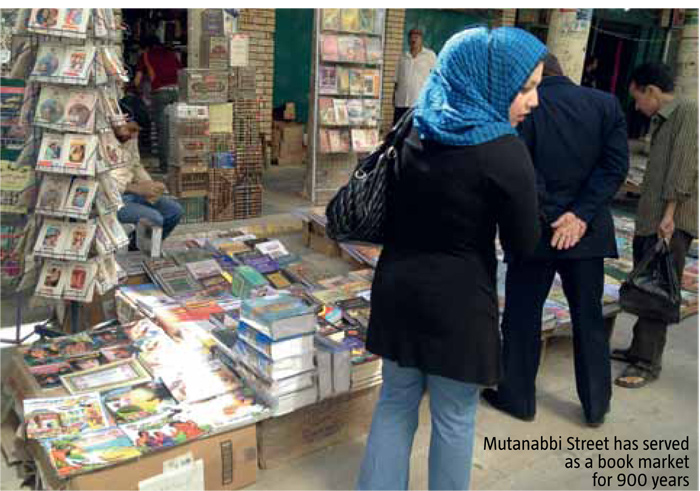

Ali can talk about the famous Mutanabbi Street book market for hours. In its 900 years of existence, the market only ceased to operate once – after a 2007 terrorist attack. He also tells me about his Facebook-organized tours to Babylon and the National Museum of Iraq, looted during the first months of the war and still closed. Ali is not going to leave Iraq. His mother will also stay because he is her only child now. Her daughter died of cancer caused by radioactive weaponry employed by the US army. Her older son was kidnapped in the bloody year of 2005. “We even paid ransom. They promised to return him in an hour. We waited. A day, a week, a month, a year. Childhood in Baghdad is not easy when bombs land on your home and there is no water or electricity. You can’t trust anyone and have to choose your friends extremely carefully. So many guys died only because they were friends with wrong people,” Ali says of his childhood.

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, CORRUPTION AND OIL

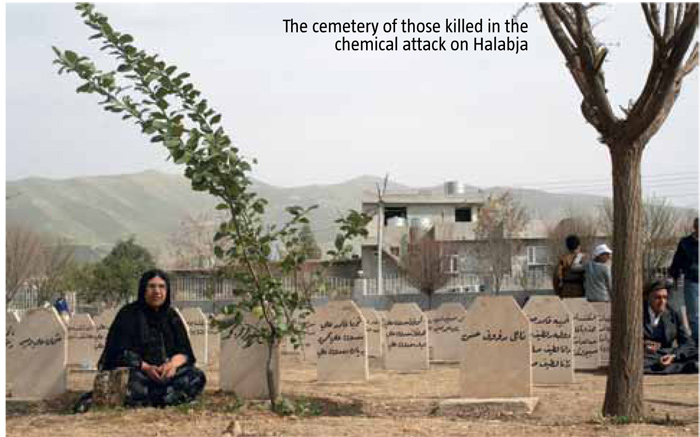

When we talk about the legitimacy of the military campaign, the locals mention that the weapons of mass destruction – the cause for the invasion – were never found, while the CIA intelligence reports George W. Bush referred to were incorrect. On the other hand, in Iraqi Kurdistan, they recall Halabja, a town on the Iranian border where Saddam Hussein used chemical weapons against local Kurds 25 years ago in spring 1988. It was the biggest gas attack in history, killing 5,000 people and injuring 20,000.

“I survived because the tobacco plant I worked at was in the suburbs,” Amina Ahmad, 80, recalls. “All survivors fled to the mountains and Iran. People died inhaling gas fumes that smelled like apples.” “Where was the international community? Where were the Arab leaders when Saddam was killing us – not just Kurds, but all Iraqis? International law is only remembered when someone can benefit from it,” Halabja locals add. A no-fly zone was introduced over Iraqi Kurdistan after the war in 1990-1991 and Baghdad stopped controlling three autonomous provinces. This also meant no more state funding for them.

READ ALSO: Relations Between Israel and the Iraqi Kurds Continued to Grow

“True, I didn’t go to school because there was none in this area when Saddam was in power. Now, life is better compared to the time when we had nothing and were absolutely poor,” says Jamal, yet another Halabja local pointing at restored streets. Kurdish human rights advocate Husha'ar Salam Malow recalls his visit to Estonia and wonders why Estonians were so unhappy with the Soviet Union after it had built most local buildings and roads. Then, he says: “The current parliament building was built under Hussein but does it really matter after he killed people? When my father went to work, we said goodbye as if we wouldn’t see each other again.”

Today, Iraqi politicians can freely ask questions about discrimination by the once pro-government Sunni minority, concentration of power in the hands of Premier Nuri al-Maliki, torture in prisons and police stations, impunity of law violators, the lack of guaranteed security, and rampant corruption.

According to international organizations, Iraq was one of the top ten most corrupt countries in the world. “Once, I was taking a local Al-Qaeda leader to hand him over to the Iraqi court,” says a former Iraqi-born soldier who served in the US special forces. “He offered me USD $40,000 for letting him escape, insisting that he would be released anyway. ‘How much did you pay them?’ I asked him when the terrorist called me three days later as he promised. He said he gave them USD $10,000.”

READ ALSO: Time Bomb

Meanwhile, Iraq owns some of the richest oil and gas deposits on the planet. Iraqi Kurdistan, a home to 6.5 million or 17% of Iraq’s population, sits on one of the richest oil deposits in the world, although these had barely been exploited before 2003 due to international sanctions. Now, oil giants like Exxon Mobile are transferring production northward and dropping contracts in the south despite Baghdad’s disapproval because it has become too expensive to protect their facilities there. “Once, a Western country sent its Foreign Affairs Ministry delegation. The armed escort from the airport to the Green Zone (in Baghdad – Ed.) cost them USD $7,500 for three hours,” says Hemin Hawrami, member of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (headed by the autonomous governorate Prime Minister) in charge of international relations.

Iraqi Kurdistan offers oil companies convenient working conditions, including the right to compensation for the exploration of new fields. The prospect of finding oil is 70%. Overall, China is one of Iraq’s biggest trade partners. The economic and cultural presence of the Far East is plain to see: cars on the streets are mostly Japanese and South Korean; the locals watch South Korean and Indian soap operas.

Despite the heavy imprint of the war and permanent threat of terrorist attacks, civilized life is gradually being revived in Iraq a decade after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. There is still a long way to go, however, to stable peace.