The collection of signatures to make Russian an official language in Latvia was started in the spring of 2011 by an organisation with an innocent-sounding name – the Native Language Society – led by Vladimir Linderman, former leader of the Latvian branch of the National Bolshevik Party. The campaign took place in November 2011 and brought in about 187,000 signatures, more than the necessary minimum of 154,000. The issue had to be either considered in parliament or put to a referendum. The Saeima refused to even put it on its agenda, so the organisers sought a referendum.

It was clear from the start that this issue was merely a tool to destabilise a country gripped by political crisis last year. A 25-27 October 2011 poll by TNS Latvia revealed that 29 per cent of citizens favoured the idea while 61 per cent opposed it.

That is why Nil Usakov, Riga Mayor and leader of Harmony Centre, the biggest political force in the Latvian parliament to represent the Russian-speaking minority, spoke out against the referendum and even accused radicals from Native Language Society of a provocative step which would end up being dangerous foremost to the minority itself while at the same time strengthening the popularity of nationalist Latvian forces. However, when his Harmony Centre failed to forge a coalition with the centre-right Unity and Zatlers’ Reform Party after the snap September election, his rhetoric changed abruptly – now he was suddenly in support of the referendum. Usakov rationalised his decision by saying that he did not believe in a positive outcome and did not even think Russian needed to have official status but said he wanted to attract attention to the problem of “political discrimination” against Russian-speaking citizens which he found in the ruling coalition's rejection of Harmony Centre.

NATIONAL IDENTITY

The Latvian leadership, most political forces and NGOs put in tremendous effort to rally society to defend Latvian as a primary marker of Latvian national identity. President Andris Berzins said he was ready to step down if Russian became the second state language and urged citizens to remember that Latvia was the only country in the world “where the Latvian language and all things Latvian can exist and where true patriots can be developed and united.”

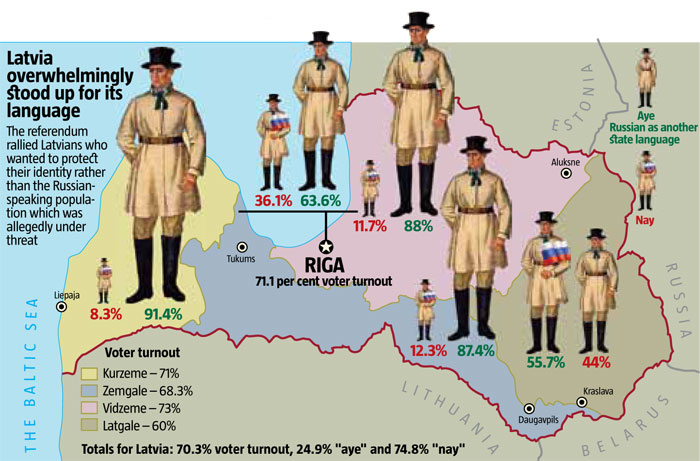

Consequently, Latvians, perceiving a threat to their national identity, became far more mobilised than the Russian-speaking population whose rights were allegedly being hurt. The average turnout across the country was 70.7 per cent with a mere 60 per cent in the Russian-speaking eastern region of Latgale and 73 per cent and 71 per cent respectively in the mostly Latvian Vidzeme and Kurzeme. Overall, voter turnout was higher than for the referendum on EU membership – 1.1 million compared to 1 million. Latgale, with a 57 per cent approval rate, was the only region that voted for amending the Constitution. Even in Riga, where Russian-speaking citizens dominate, only a mere 36 per cent voted yes.

THE RUSSIAN FACTOR

But Linderman said that “the referendum is not the end.” The Native Language Society plans to use its results, especially in the regional perspective, in European institutions to apply pressure on Latvia on the issue of language, at least in some regions. Moscow is certainly ready to help.

First Deputy Chairman for Foreign Affairs of the Russian Duma, Konstantin Kosachev, said that “the situation that has arisen now (in Latvia) is abnormal, and it must be demanded that Russian be used as an official language – if not across the country, then in cities and municipalities with Russian-speaking communities.” On 19 February , Russian Foreign Ministry spokesman Aleksandr Lukashevich emphasised that the outcome of the referendum showed “disagreement with the course to build a mono-ethnic society.” Meanwhile, Moscow continues to insist that the results do not reflect the real sentiments in Latvia, because 319,000 of the Baltic state's residents still do not have citizenship.

Remarkably, Russia tried various ways to exert pressure on Latvia before and during the referendum. Solvita Aboltina, Speaker of the Latvian parliament and a leader of the ruling coalition, expressed concern over the manoeuvres of a Russian supersonic bomber TU-22M along the edge of Latvia’s air space on the eve of the vote.

The Latvian referendum on language cannot be considered outside the context of Russia’s policy in the post-soviet landscape. On 12 June 2008, newly-elected Russian President Dmitry Medvedev approved a new version of Russia's foreign-policy doctrine which included the special feature of a clear declaration of Russia's expansionist plans regarding former soviet republics, which were viewed as “a sphere of special interests.” A key means to this goal is numerous Russian minorities and other Russian-speaking peoples whom the Russian leadership calls “compatriots.”

LATVIA WITHOUT LATVIANS?

Russian radicals in Latvia rely on the idea that the Russian-speaking population of the country is a state-forming force. The official site of the Native Language Society defined the goal of the referendum as follows: “The Russian-speaking residents of Latvia must show the world that there are hundreds of thousands of us and that we will never resign ourselves to the status of outcasts in our motherland.” By “outcasts” they mean their status of an ethnic and linguistic minority and the definition of Russian as a foreign language in Latvian legislation.

That the real goal of these champions of Russian in the post-soviet territory is not to defend the rights of Russian speakers against discrimination but to establish a dominant position is further corroborated by the actual prevalence of Russian in the economic life of the country.

Former Culture Minister Sarmite Elerte, who is now an advisor to the Prime Minister on national identity issues, said after the referendum that Latvian was still not the dominant language in the public sphere in large cities and that services were not always available in Latvian. So it is important for the government to develop a strategy to prevent Latvians from suffering discrimination on the labour market where they are required to have a command of Russian. The basic assumption must be that a job linked only to the domestic market should not require knowledge of this foreign language. For example, Aleksandr Gafin, a member of the board of directors at Pietumu Banka, told the Russian mass media that “employers normally refuse to hire those who have no command of Russian, while the reverse is much less frequent. Consequently, with all other circumstances being the same, a Russian-speaking person has more prospects in Latvia than one who only speaks Latvian.” This situation is explained by the high percentage of Russians among the urban population and the ties local oligarchs have with Russian business.

Former Latvian President Vaira Vike-Fraiberga, who was in emigration in Canada and returned to Latvia in the 1990s, was shocked by the changes that had taken place in Latvian society during the soviet occupation. “Latvians quite often instantly switch to another (Russian – Editor) language as soon as a person who does not speak Latvian joins their company, while the French would never do that,” she says.

In fact, Linderman does not conceal that the goal of his organization is to restore the dominant status Russian enjoyed in the USSR. Moreover, he is trying to present the prospects of Latvia's economic development as directly dependent on the need to reject Latvian identity: “The ideology of nationalism is absolutely incompatible with the economy. It makes Latvia a hamlet. The only goal of the hamlet is to preserve Latvians themselves…Conferences must be held here; people and commodities have to constantly move; and firms have to be registered. But this immediately ruins the ideology of a ‘Latvian Latvia’, because the value of Russian increases instantly.”

Latviais indeed more vulnerable to expansion than, for example, Estonia. Estonia has a slightly smaller Russian-speaking minority, but its economy has performed better in the past several years, so Russian speakers had a stronger stimulus to integrate. Estonian Foreign Minister Urmas Paet said during his visit to Latvia before the referendum that he ruled out a similar plebiscite being held in Estonia, because there are many more people in its Russian community that understand why a command of Estonian is important and see the advantages it gives them in education and on the labour market. In contrast, Latvia struggled during the transformation period because of its much greater dependence on industrial cooperation with and providing transportation services to Russia. Former Latvian Prime Minister Einars Repse said in his comment on the referendum: “The most complicated thing is to have Latvians themselves see their future, their secure future, and development. Then the rest will join in.”

AVOIDING A REPEAT

The referendum drove home to Latvian politicians that preventive measures had to be taken to rule out any repeated attempts of the kind. The president has already said that by calling the referendum he put one of the most dearly held foundations of the Latvian Constitution – the state language – in jeopardy. So now it is time for a meaningful discussion about fixing its foundations in order to thwart any future risks to Latvian statehood. Otherwise, Latvian society will remain vulnerable to manipulation.

Aleksey Loskutov, an ethnic Russian and one of the leaders of the ruling Unity bloc, says that the government needs to step up integration for non-Latvians. While most of them have some command of the state language, it is evidently not enough. In 1996-2010, 55,500 residents of Latvia took Latvian language courses in addition to young people who studied it in school. However, the efficiency of these measures remains low due to insufficient motivation among the population and destructive propaganda coming from pro-Russian organizations.

In 2011, a nationalistic alliance promoting accelerated integration of the Russian-speaking population began collecting signatures for a referendum that would decide whether it was necessary to gradually switch to Latvian as the language of instruction in schools by 2024. However, this initiative failed to gain support, and it was only recently that a new school subject, History of Latvia, was introduced in order to instil patriotism in students regardless of their ethnic background, promote the correct understanding of complicated history issues and respect for Latvian traditions.

CONTEXT FOR UKRAINE

The linguistic issue in Latvia is a realistic illustration of what Ukraine may face. Similar to such Latvian political forces as Harmony Centre, the Party of Regions has on numerous occasions exploited the language issue while in the opposition. And, again like Harmony Centre, it takes a softer stance when in power. All parties in countries like Latvia or Ukraine play the language card merely as a way to mobilise voters, dropping the subject once the desired result is achieved. Despite this fact, the Kremlin is still interested in pushing the Russian language through*. Destabilising the situation in regions that were once the “peripheral parts” of its empire is more than a convenient illustration that the events that happened two decades ago were a mistake. As long as an external player is interested in revising the geopolitical architecture of the post-soviet territory, the language issue in countries with large Russian-speaking minorities will not be limited to “civil rights” and will be used as a political tool, which will constantly threaten the smaller states' sovereignty and national identity.

*Read about the integration of Russian-speakers into the Ukrainian-speaking community and the status of Ukrainian in Ukraine in our next issue upcoming on 16 May 2012.