The prospect of US missile defense deployments in Europe has urged Russian President Medvedev to warn the West that Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles will be equipped with “modern offensive weapons systems, ensuring our ability to take out … missile defense systems”. Moreover, Russia will discontinue the disarmament process and withdraw from the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START-1). As a result, many observers now lament the “end of the reset” and propose the opening of discussions as to whether Russia can substantiate its bold statements with action and what all this will mean for other countries, first and foremost, its neighbors.

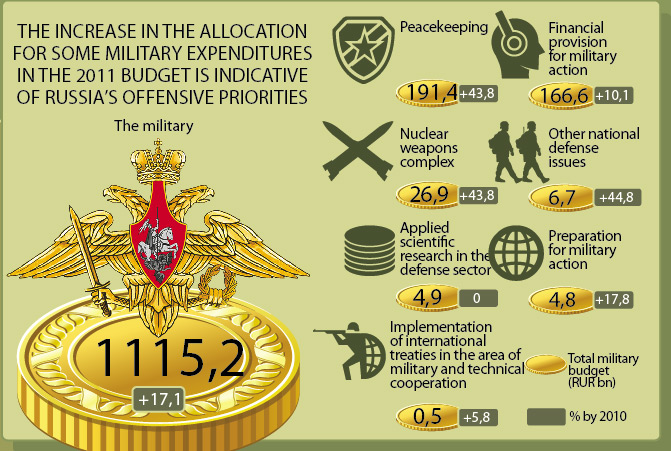

Over1994-2010, theshareofmilitaryspendingintheRussianbudgetshrankmorethantwofoldfrom28.2% to12.5% whilethe2010 globalfinancialcrisisforcedthecountrytocutevennominalmilitary expenditures. However, President Medvedev recently announced a significant increase in military spending in the nearest future, while parliament has already approved the relevant 2012 draft budget in the first reading.

The renewed priority of the military-industrial complex in the economy and the “surrounded fortress” rhetoric is completely in line with Vladimir Putin’s nostalgia for the loss of the state as a result of what he considers to be the “greatest catastrophe of the 20th century”. Thus, it would be a reasonable component of the program for its revival.

The 2011 military budget was nearly USD 50bn (RUR 1.52trln), i.e. almost 1.5 times more than total expenditures on education, health care and utility service combined. In 2013, the total defense budget should, at the current rate, amount to USD 70bn, which is USD 500 per Russian. The government has promised the military a threefold salary raise as of 2012.

IN PURSUIT OF ENEMIES

Due motivation of the nation by the government is required for a rapid increase in military expenditures. In Russia, the designation of an “external enemy” is on a high level. Over the past few years, it has been focusing on initiatives by its neighbors that seem more defensive than aggressive, such as the attempts of the Baltic States and Georgia to reinforce their security through integration with NATO and its program to build a system for protection against potential missile attacks.

Lately, Russian aircraft have flown much more often in Baltic airspace, each time escorted by NATO planes.

Georgiacontinues to be another irritant. The real purpose behind the Russian military assault against Georgia in 2008 and the establishment on its territory of the Abkhazia and South Ossetia “states”, recently recognized by Dmitri Medvedev, was to stop Georgia’s NATO integration. Any step Tbilisi takes towards Brussels is accompanied by hysterics on Russia’s part.

THE POST-SOVIET FRONTLINE

In 2004, the Russian Defense Ministry started to revise its previous decisions regarding the future of Russian military units located abroad. Russia is no longer going to withdraw them. On the contrary, their number remains intact or declines marginally while the overall size of the military is shrinking. Moreover, they are reinforced with air battalions and other elite military units including precision-guided artillery, intelligence units and the like.

In 2010, the Kremlin managed to impose a deal to extend its military presence in Sevastopol, Ukraine, until 2042; currently it is negotiating the extension of Russian presence at the base in Gabala, Azerbaijan, until 2025 in exchange for Moscow’s support of the Nagorno-Karabakh issue, and is preparing to sign a contract to rent a military base in Tajikistan for 49 years. The integration of Russian and Kazakh missile defense systems is in full swing.

Since its August 2008 assault against Georgia, Russia has drawn its Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) partners into a verbal confrontation with NATO. The declaration passed at the CSTO summit from September 5, 2008, supported “Russia’s proactive role in facilitating peace” in the CIS and called on “NATO states to take into account all the possible consequences of its expansion eastward and the dislocation of new missile defense facilities in territories bordering CSTO countries.” Six months later, on February 4, 2009, CSTO passed a resolution to create Collective Rapid Reaction Force (KSOR) to “repulse military aggression, conduct anti-terrorist operations”. All CSTO members had signed the treaty by October 20, 2009. The Central Asian regional force was the CSTO’s first combat brigade. Today, it is comprised of 10 battalions with nearly 4,000 troops, 10 planes and 14 helicopters at the Russian airbase in Kyrgyzstan. A specific feature of these units is the possibility, for example, to involve Belarussian and Armenian battalions in military operations far beyond their territories or national interests.

The powers of the CSTO are expanding, with the organization preparing amendments to its charter to move away from the consensus principle in the decision-making process. It is also a testing ground to find out how it can increase its membership with other countries, which are frustrated with NATO. On April 3, 2009, a CSTO Secretariat member said Iran could gain observer status in the future. This scenario is very possible, given the latest threats to review cooperation with Iran in response to the expansion of the missile defense system and the deepening of differences between the West and Teheran.

A COLOSSUS ON CLAY LEGS

Despite being in the top five armies, based on formal criteria, such as troops, numbering up to 1 mn, strategic assault weapons and space program, the Russian army is no longer able to dominate in the world, as it did during the Cold War.

An army’s combat capacity depends on the physical and psychological shape of its staff more than it does on weaponry. More than 200,000 potential troops avoided conscription, while the crime and suicide rate within the military continues to grow annually. Officers are now publicly showing their frustration at unfulfilled promises. In 2002, Vladimir Putin made a public commitment, stating that the problem of housing for current officers and army veterans would be resolved by 2010, and reaffirmed it in 2007.

According to most experts, the reform launched by Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdiukov after the five-day war against Georgia in 2008 failed to solve most of the tasks set before it. On the contrary, mass layoffs in the army when 200,000 officers were fired and 140,000 warrant officers were forced to take early retirement, and the planned reduction of military academies from 70 to 10, led to strong opposition from members of the military, including the resignation of a number of top commanders.

It appears that the military-political confrontation with NATO is just a play to the gallery that the Kremlin is trying to use for the purpose of consolidating the nation around itself while fuelling the image of an “external enemy”, which is standard for the Russian collective mind. Yet, this strategy is hopeless. The experience of the Warsaw Pact, much more powerful and numerous compared to the Russia of today and the CSTO, showed its economic inability to oppose NATO. Yet, for Russia’s neighbors, Ukraine first and foremost, the former’s militarization programs implemented against the backdrop of stated revival ambitions (the establishment of a Eurasian Union “on the ruins of the USSR”) during Putin’s new term in office, will likely be a very realistic threat. The only way for Ukraine to protect itself from it, is by rejecting the illusionary non-aligned status and activating a course towards integration into the Euro-atlantic collective security system.

The Kremlin is clearly trying to solve yet another task through militarization. The purpose of increasing defense funding is to soothe the military, which is becoming ever more frustrated. Of late, this frustration has even been seen at the highest level of the General Staff. A conflict with the army is extremely dangerous for any dictatorship, particularly in a crisis where public frustration threatens to express itself in the form of open protests.