Iran has been in the international headlines constantly over the last couple of months, with the prospect of military action looming on the horizon with every belligerent statement made by President Donald Trump, and every Iranian threat to fight back any attempted US aggression. While the US and its allies in the region clearly enjoy a conventional superiority over Iran in terms of the quantities and quality of military assets they can bring to the potential fight, the Islamic Republic possesses multiple tools at its disposal through which it could retaliate asymmetrically across the entire Middle East and in Afghanistan. What is more, it has actually been using those for years across the entire arc of instability from the Arabian peninsula through Syria to Afghanistan, which, coupled with the suspicions of the “hawks” in Washington that Iran’s ultimate goal is to develop nuclear capabilities in violation of the nuclear deal, has triggered the ire of the current US administration.

Given its recognized inability to compete with the US in conventional warfare, Iran has resorted to its own version of Hybrid Warfare – ‘Soft War’ (‘jang-e-narm’) in response to its perceived challenge by Western and in particular American “soft power”. Just like Russia, Iran also views soft power as an existential threat to the stability of its regime, as it perceives it as an American hybrid tool to foment popular protests and potentially – an uprising within Iran against the theocratic regime. Therefore, the Iranian-style hybrid warfare has become an element of Iran’s strategic culture of gradual, but constant expansionism by dividing the adversaries surrounding Iran – the US as the guarantor of stability in the region, and its allies – the Arab monarchies in the Persian Gulf. In that regard, Iran’s hybrid warfare is structurally similar to the models of Russian hybrid warfare as practiced during the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, as it uses similar elements – from historical, socio-cultural, legal, diplomatic and economic to conventional military and covert ones.

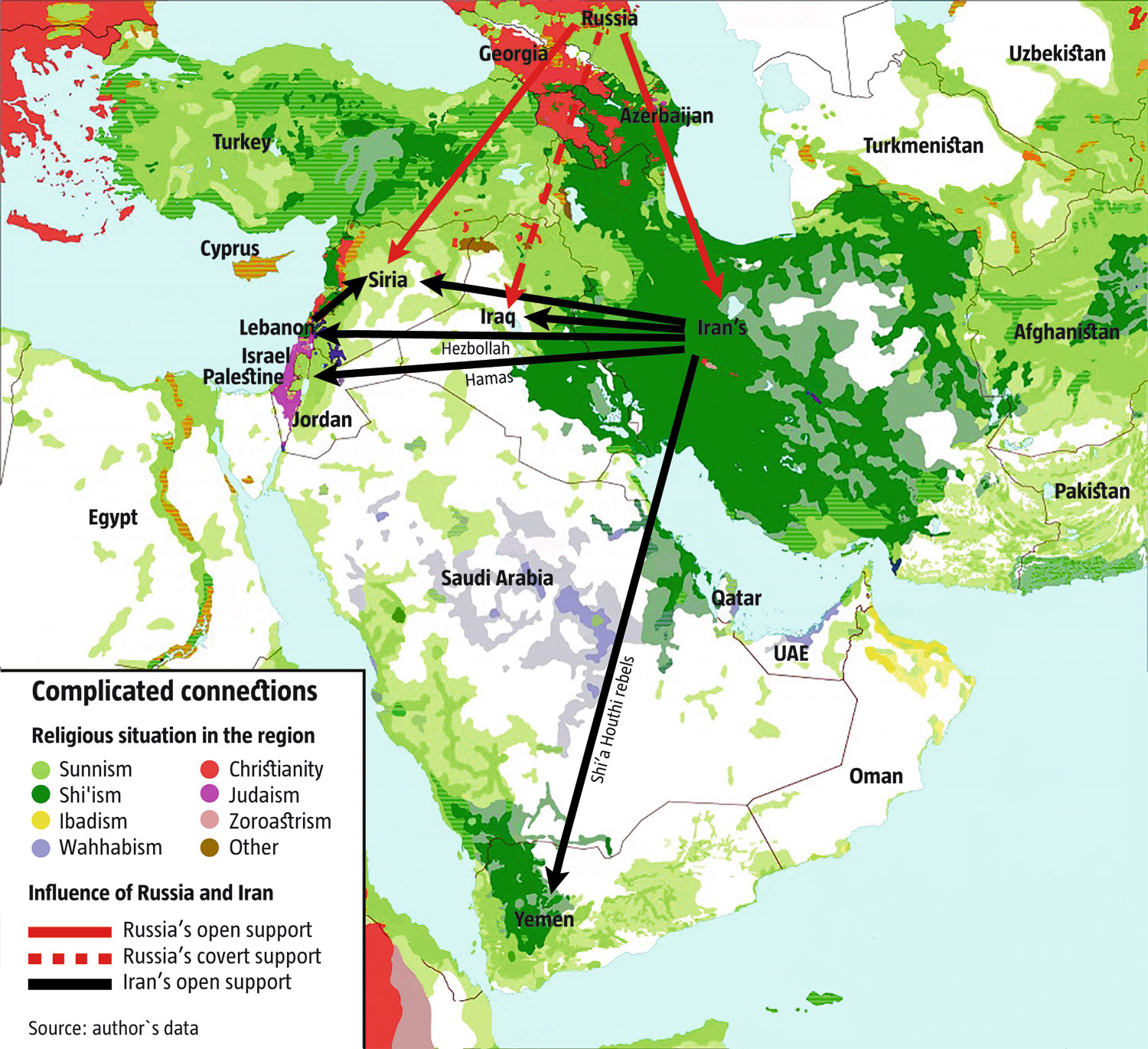

The strands of Iranian Hybrid Warfare can, therefore, be identified, as follows: historical – the past Iranian imperial domination of the Arab Middle East; religious – the exploitation of the Sunni-Shi’a sectarian divide in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrein, and Yemen; geopolitical – the threatening of strategic maritime chokepoints, such as the Straits of Hormuz and Bab-el-Mandeb; military – Iran’ nuclear ambitions and direct military support to its allies in Iraq and Syria; diplomatic – Iran’s support for the Shi’a-dominated political systems in Iraq, Lebanon and Syria; economic – the economic penetration of Iraq and the financial support for the embattled Syrian regime; and last, but not least – covert, the most prominent examples being the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) support and training of Shi’a militias in Iraq, the support for the Shi’a Houthi rebels in Yemen, and Iran’s sponsorship of Hezbollah in Lebanon, but also of Hamas in Palestine.

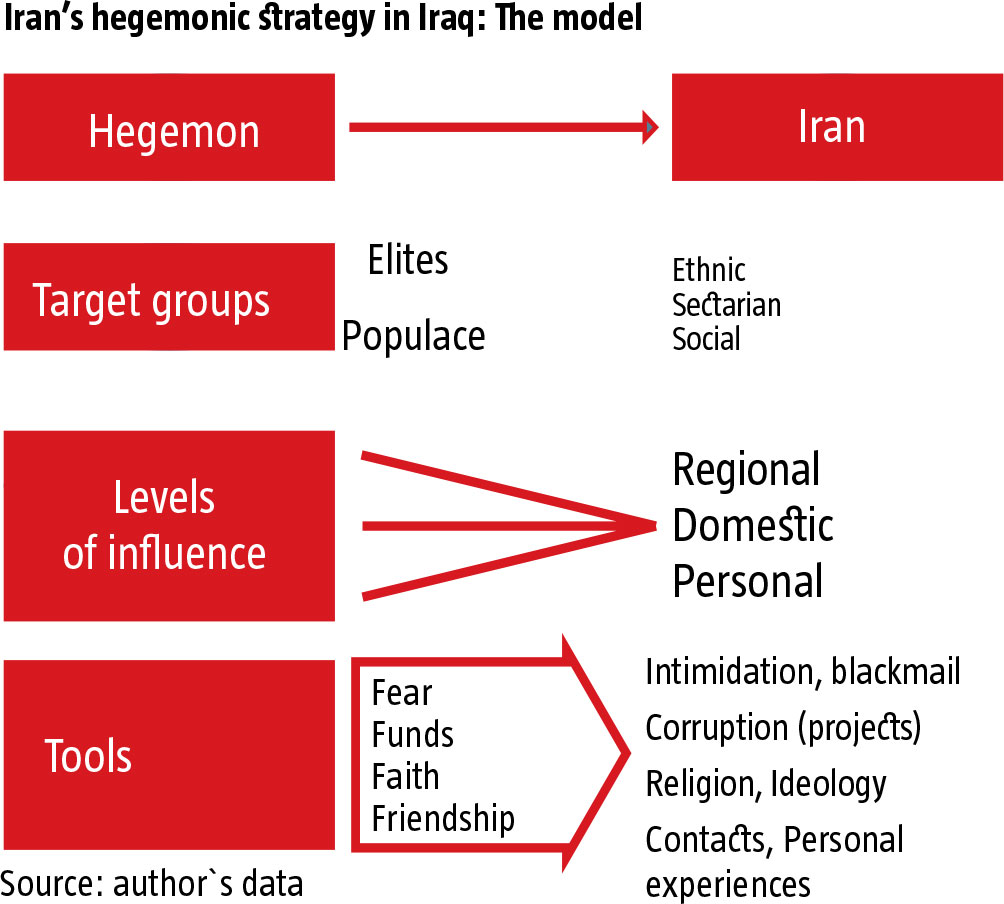

The patterns, by which Iran has established a hegemonic presence in Iraq, for example, offer a classical example of the Iranian penetration of a neighboring state that has historically been its primary strategic competitor in the Middle East. The featured model provides an analytical assessment of Iran’s domination of Iraq, that revolves around its ultimate objective of being the stronger actor in the neighborhood (the hegemon). Iran’s preferred target groups are both the elites and the population of Iraq, especially the ethnic, religious and social groups that could best promote its long-term interests. Iran influences those at the personal, domestic and regional levels through a hybrid toolbox that combines “Fear, Funds, Faith and Friendships”, and whose darker dimensions involve intimidation and assassinations, the corruption of government officials and community leaders, bound to Iran by sectarian linkages or personal bonds.

The ongoing Iranian attempts to achieve hegemony throughout the Arab Middle East seek to exploit, but also inevitably exacerbate the sectarian divide in the Middle East. Iran’s expansionism is defined by Iran’s cultural affiliations with the Shi’a populations in the region, and the sectarianism promoted by Iran ultimately has a strong destabilizing effect on the entire region, as it triggers strong opposition and push-back on the regional and international scenes by the dominant Sunni powers in the region represented by Saudi Arabia, the other Gulf Cooperation states, and the Arab League, as a whole.

Iran in Afghanistan: The Art of Playing Both Sides

In Afghanistan Iran is faced with a different “human terrain” compared to Iraq – one based on linguistic and cultural affiliations that also comprises the traditionally suppressed Shi’a sectarian element. While Iraq is dominated by Arab-speaking populations – both its Shi’a majority and Sunni minority, the groups in Afghanistan that share direct linkages with Iran’s ethno-religious characteristics are the predominantly Sunni Persian-speaking community (the Tajiks) and the Persian-speaking Shi’a minority (the Hazaras).

Iran’s long-term objectives in Afghanistan are defined by what it views as systemic threats posed by Sunni extremist groups – the Taliban and Al-Qaeda; but also by the long-term US and NATO presence in that country. Of course, deeply-rooted economic issues, such as the flow of drugs and migrants originating from Afghanistan are also of concern for Iran. Iran traditionally views itself as the dominant player in its relationship with Afghanistan, and inevitably tries to shape the future political and cultural outlook of that country, especially its future after the potential departure and disengagement of NATO there. In that regard, Iran is pursuing a set of short-term goals that run contrary to stability through its attempts to subvert the NATO coalition efforts in Afghanistan. Iran is playing both sides by maintaining friendly ties to officials in Kabul, and by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) clandestine supply of weapons to Taliban groups in order to undermine the NATO-led stabilization and speed up the NATO troops’ withdrawal. Afghan and US officials have long accused Iran of supporting the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, especially Iran’s Quds Force and its Ansar Corps, based out of the Iranian city of Mashhad. The fact that by doing so Iran is seemingly crossing the Shi’a-Sunni divide should not be viewed as a leap of faith, as Iran has proven through its support for Hamas and other radical and Jihadist groups in the Middle East, that it can successfully cooperate with radical Sunni groups who share its anti-Western agenda.

In Afghanistan Iran is able to apply extensive tools combining hard and soft power – both its “soft war” (“jang-e-narm”); and asymmetric warfare (“jang-e-na-monazzam”) across the entire military and non-military spectrum. Iran’s religious and socio-cultural influence is manifested by the promotion of Shi’a Islam along with Iranian culture, especially among the Shi’a Hazaras; by the numerous Afghan students in Iran; and by promoting the Persian language culture that both Iran and Afghanistan share. Cultural influence, just like in Iraq, often translates into political influence, as Iran uses corruption to influence Afghan politicians, along with exerting diplomatic pressure to have anti-NATO statements pushed through the Afghan Parliament. Iran also benefits from strong economic influence over Afghanistan based on Iranian investment and commercial engagement, which feature an imbalanced economic relationship in favor of Iran, and where the supply of Iranian oil and gas are used as political tools. Last, but not least, Iran uses extensively to its advantage the issue of Afghan migrants in Iran (over 2.5 million; of which nearly 1 million refugees) as a powerful tool for exerting pressure based on threats of mass deportations, that when followed on could trigger humanitarian and political crises in Afghanistan.

The Iranian hegemonic model that is used extensively in the Arab Middle East is, therefore partially replicated in Afghanistan, based on structurally similar tools and primary agents of influence. From the Iranian point of view its rationale is twofold – the protection of traditionally marginalized groups, such as the Shi’a in Afghanistan, and using them to promote and expand Iran’s interests. Iran, however, also plays a perilous opportunistic game that ultimately contributes to the destabilization of the country by supporting non-status quo actors, such as the Taliban, which can only trigger more conflicts and bring about stability in the long-run. Iran and Afghanistan, thus, share an uneasy relationship derived from Iran’s attempts to play a dominant role in their relationship.

The Russia-Shi’a Axis and the Logic of Russia’s Strategic Orientation in the Middle East

The ongoing Russia operations in Syria since 2015 have revealed the shaping of a de facto ‘axis’ between Russia and the main governments and non-state armed groups under the control of religious groups belonging to the Shi’a sect of Islam. Those include the regime in Tehran belonging to the most numerous branch of Shi’ism – Imamism, the government in Baghdad dominated by the Iraqi Shi’a, as well as the regime in Syria, whose top leadership and support base belong to the Gnostic sect of the Alawites, an offshoot of Shi’ism. The non-state actors in this ‘axis’ are the Shi’a militias in Iraq and Lebanon (Hezbollah). They are traditionally supported by Iran, but they also fight alongside Russian forces in Syria as part of the Russia-controlled “integrated forces groupings”, the Russian military’s hybrid expeditionary formations.

Each of the elements of this alliance has diverse identities – socio-cultural and ideological, and their interests do not always overlap completely. Russia is a Christian Orthodox country with a Russian-speaking majority, but it is also the legal successor of the Soviet Union with its militant secularist transnational ideology of Communism. Iran is a multi-national state with an ethnic Persian linguistic and cultural majority, and dominated by the Imami (‘Twelvers’) branch of Shi’ism. The Shi’a in Iraq are ethnically and linguistically Arabs, as are the Lebanese Shi’a. The Syrian Alawite sect also comprises speakers of Arabic who are viewed within Islam as a distant offshoot of Shi’sm, or even as heretics by Sunni radicals and traditionalist alike. They are largely secular, and form the power base of the ruling Syrian Ba’athist regime, which combines elements of Arab socialism and pan-Arabism. Three major relationship nodes can be identified within this complex set of alliances: Russia-Syria (with Syria as a regional ally and client-state of Russia); the Russia-Iran strategic partnership; as well as the node comprising the linkages joining Iran with 1) the Iraqi Shi’a politicians and militias; 2) the Hezbollah Shi’a militia in Lebanon, and 3) the client relationship Iran has developed with the Alawite-dominated Baathist regime in Syria during the course of the ongoing civil war; 4) Hamas in Palestine, and 5) the Shi’a Houthi militias in Yemen that are supported and armed by Iran and used as proxies against Saudi Arabia.

Regardless of the Alawites’ traditional secular orientation and Ba’athist pan-Arabist ideology, at the strategic level the Iran – Syria alliance has become possible for a) historical reasons – namely, the shared hostility (Iran) and rivalry (Syria) with the former Sunni-dominated Baathist regime in Iraq; and b) more contemporary ones, ranging from their joint opposition to the traditional Sunni regimes in the Arabian peninsula; their perception of Jihadist extremists claiming affiliation with Sunni Islam as one of their primary existential threats; their historical hostility toward Israel; and their support for Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

Russia’s long-term objectives should be analyzed within the larger context of Russia’s strategy in the Middle East to replace the US as the hegemonic power in the region, which every nation-state or ethnic group in the region would be forced to talk to, regardless of the Soviet history of supporting mainly non-status quo powers and groups in the Middle East. Russia clearly has its preferences, and it has taken sides in the ongoing Sunni-Shi'a divide by joining the Shi’a forces since the fall of 2015. Prior to the launching of Russia’s campaign in Syria in September of 2015, leading Russian military analysts argued that, "It is perfectly obvious that in the Sunni-Shi'a confrontation that is taking shape in the Middle East, Russia must take the side of the Shi'a due to natural pragmatic reasons. In the first place, at least 90 percent of Islamic terrorism is Sunni. Secondly, 95 percent of the Russian Muslims are Sunnis. Correspondingly, the most serious threat for us is exactly Sunni terrorism. The enemy of my enemy is my friend, as in this case the logic of it is self-evident. In the future the situation might change, but currently the situation is exactly like that.” (Hramchihin, Military-Industrial Courier, 7 September 2015).

This view provides the rationale for Russia to join what is a de facto ‘Shi'a axis’ from Tehran through Damascus to Lebanon to isolate the West and counter both Jihadist extremists, such as al-Qaeda and Da’esh, as well as the moderate Sunni states – the Arab monarchies in the Mideast, as well as Turkey. Russia’s participation in Syria was initially perceived by the Sunni Arab powers as taking sides in the Sunni-Shi’a sectarian war, and in late 2015 the Saudi Sunni clerics issued a fatwa against both Iran and Russia calling for jihad against them. Ultimately, through the combination of its diplomatic efforts, economic (energy) projects, and military victories on the ground in Syria, Russia has achieved the impossible, namely, forcing all players in the region to work with it – the Arabs and Israelis, Turks and Kurds, Shi’a and Sunni, the Taliban and the Afghan government, India and Pakistan, etc. Paradoxically, instead of ruining its relationship with the Sunni powers in the region, Russia’s active military support for Assad's regime has so far resulted in positioning Russia as one of the “king-makers” in that turbulent region.

The Alignment of the Strategic Objectives of Russia and Iran in the Region and the Limits of US Options

As matters stand now in the Middle East, the Shi'a world is largely dominated by anti-Western forces led by Iran, with even moderate Shi'a groups and leaders across the region not being particularly pro-Western. This continues to bring benefits to both Russia and Iran by exploiting the ongoing political and sectarian divides in the region in order to reduce the threat to the Syrian regime, decrease the US and Western influence and destabilize the US Sunni Arab allies in the Gulf region. Ultimately, however, the brutal Russian campaign in Syria, combined with the ongoing Iranian attempts to achieve hegemony by destabilizing the Arab Middle East through the use of Shi’a radical groups as Iranian proxies, can only exacerbate the overall tensions in the Middle East, with a strong destabilizing effect on the entire region.

Given the global scope of Russia’s Hybrid Warfare as the 21st century style of warfare favored by the current Russian political and military leadership, and Iran’s own hegemonic ambitions in the region, the “arc of instability” across the Middle East to Afghanistan should be regarded as one of the primary theaters of both Russian and Iranian hybrid warfare, where both states apply political, diplomatic, legal, economic, socio-cultural and information pressure against the US and NATO, together with overt cooperation with, and covert support for militant groups, Shi’a and Sunni alike. In this regard, the current Iranian confrontation with the US serves the Russian strategic objectives perfectly, as the United States is portrayed as an irrational and aggressive superpower that prefers conflict to diplomatic deals and dialogue, and positions Russia as the “responsible” status-quo power. A potential military conflict with Iran also threatens to disrupt the flow of oil and gas from the Persian Gulf, thus making the supply of energy resources from Russia to the West and China indispensable in the future. Iran will also inevitably activate its network of proxies across the region to target US, Saudi and UAE military facilities and civilian infrastructure.

Currently, the Trump Administration’s reluctance to respond in kind to Iranian provocations such as the magnetic mines attack against oil tankers in the Straits of Hormuz and the downing of the US reconnaissance drone over what the US claims were international waters, sends a strong message to both Iran and the US allies in the Gulf, that the US is hesitant and inconsistent in its proclaimed firm approach toward Iran. This has the potential to deal a strong blow to the image of the United States as the superpower that has traditionally provided stability to the entire region by protecting its allies there (Saudi Arabia and Kuwait), and punishing the perpetrators who have dared to challenge the status-quo (Saddam Hussein’s Iraq). This is the adverse strategic environment in which the United States will be forced to operate should President Trump decide to choose military strikes as the US primary tools of subduing and punishing Iran. So far, despite all his belligerent rhetoric, he has shown unusual restraint by abstaining from launching conventional military strikes, opting instead for information, economic and diplomatic pressure, targeted economic sanctions and cyberattacks against Iran’s military. The coming weeks will show if this strategy will be sufficient to force Iran to back down (likely not), or whether both sides will inexorably go down a spiral of confrontation, as Iran tries to save face and prove to its regional allies and its population that it will not yield to American pressure, and that the United States is still a global superpower capable of imposing its will on a rogue power in the Middle East by punishing it for its alleged non-compliance of the nuclear regime, and its continuous conventional and hybrid attacks against US forces and US allies, and other provocations across the region.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook