It’s been quite clear for some years now that the leadership of the Russian Federation dreams of reviving the Soviet Union. Moreover, it’s not just a matter of extending geographic boundaries, but also about its influence around the globe. And so the Kremlin is sparing no effort, cost or soldiers to restore the illusory glory of its one-time empire. This includes several simultaneous objectives: dependencies are being established with individual politicians and even governments in order to protect and promote its interests abroad; the unity of the western world is being undermined in order to weaken its capacity to counter Moscow politically, economically and militarily.

What’s more, the methods have hardly changed since soviet times. Odious African dictators are offered protection against colored revolutions that are supposedly inspired by the CIA, the Pentagon or Mossad. Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad keeps his seat in exchange for oil and Russian military bases. Meanwhile, the fate of “military advisors” or of local residents who suffer from “humanitarian” bombardment means nothing at all. Nor does distance: “Russkiy Mir” can appear wherever the military transports of the Russian Federation can fly.

But some games are far more sophisticated. For more civilized European countries, time-tested methods of bribery and blackmail or killer combinations of the two are used. For example, a particular politician can be semi-officially “bought” by offering an interesting post or business deals. One-time German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder lobbied Russian interests in Germany and the EU: his reward was being appointed chair of the shareholders’ committee of Nord Stream AG as soon as he left office and joining the board of directors of Gazprom.

Or a group of pliable MPs from the EU is offered a fully-paid junket to occupied Crimea – undoubtedly with a small “honorarium” of freely convertible Russian hospitality in exchange for keeping their eyes wide closed, saying nice things on television, and acting as though the “Russian” peninsula had official status. There’s no question that every step by these politicians on Russian territory is carefully recorded by the FSB, to be used, when necessary, for blackmail in Moscow’s interests. For a mere €70 million, Russia was recently indulged for its aggression in Ukraine and its delegation returned to PACE without any conditions or sanctions. Nor is money the only form of influence. Often we see convenient contracts, especially in the fuel and energy sector.

RELATED ARTICLE: Open letter to Vladimir Putin

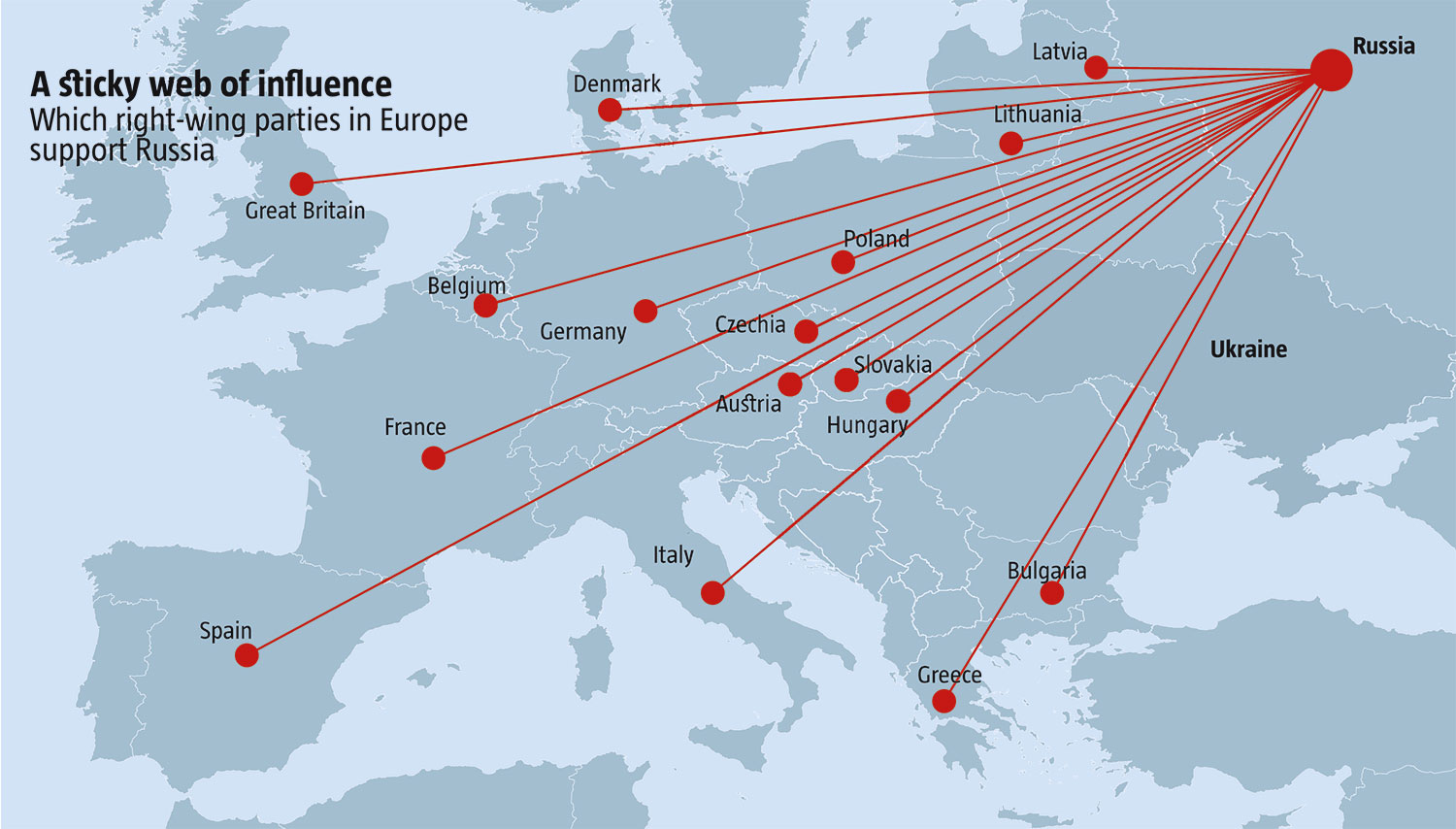

And when the need arises for a strong strike from within, Russia can always use its petrodollars to finance political parties that are willing to promote the right ideas among their domestic voters. Logically, Russia is trying to exploit the more right-wing and authoritarian segment of the political spectrum as a counterweight to the largely liberal established democracies of Europe. This means countering a unified Europe, NATO, multiculturalism, globalization, George Soros, and market economics. Some of these links were established back in soviet times, such as friendly relations with Austria, and some are based on the theory of pan Slavism, which are more typical of the Balkans and Eastern Europe. A 2014 report by the Hungarian think-tank Political Capital Institute, which came out at the beginning of the open phase of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, 15 right-wing parties in 13 EU countries reported a positive attitude towards the Russian Federation and only 3 were negative. One of the popular excuses of right-wingers in EU countries is the desire to restore former glory (see A sticky web of influence).

Following the principle of keeping its eggs in several baskets, Moscow simultaneously supports both right-wing and left-wing parties and extreme entities. In Germany, these include the Linke and AfD. The same happened in Greece. When the e-mails of one-time secretary of the Russian Embassy Georgiy Gavrysh were hacked, his efforts to set up a network of influence in that country under the tutelage of Russian chauvinist ideologist Aleksandr Dugin. Over 2008-2013, he established friendly relations with Greek intellectuals and business owners who supported opposite sides at the time – the right-wing Independent Greeks Party and the left-wing Syriza – while also provided support to ultra-right extremists in the Golden Dawn movement who have basically called for a military junta in Greece. In the 2019 election, this party was unable to meet the threshold, but until that time it had boasted nearly 20 seats in the national legislature. In addition, Greek neo-nazis managed to get two seats in the European Parliament. One of the two representatives of the party, Yannis Lagos, cannot leave Greek territory, as he is one of the suspects in the 2013 murder of anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas.

In the run-up to the 2017 presidential election in France, Moscow nearly officially provided a loan for the campaign of Marine Le Pen’s National Front. While there are no exact figures for the amount involved, most sources quote €40mn, even though Le Pen herself only admitted to €9mn. At the time, she was having serious financial problems because French banks were rejecting her loan applications, while the European Parliament required her to return nearly €340,000 that she had appropriated by claiming wages for fictive workers at her campaign headquarters. At this critical juncture, Russia came to her assistance and immediately Le Pen’s rhetoric began to promise to acknowledge Crimea as Russian and to lift sanctions if she were to win. During the recent Gilets Jaunes protests in France, well-trained men with Russian accents were noticed among the crowds.

Russia’s relations with Hungary’s Jobbik party are equally warm. Jobbik politicians both recognized the March 2014 pseudo-referendum in Crimea and travelled to ORDiLO as observers in equally-fake elections there. Under the leadership of this party, Hungary has continually played the minorities card in relations with Ukraine and used this to block Kyiv’s cooperation with NATO. Prime Minister Victor Orban boasts about his friendship with Vladimir Putin and was famously quoted as saying that sanctions against Russia were simply “shooting yourself in the foot.” Meanwhile, news has come out that Hungary was planning to buy gas bypassing Ukraine, the number of Russian joint ventures keeps growing, such as the building of the Paks NPP in central Hungary, as are investments and spies. Russia’s military intelligence arm, the GRU, has been linked to Magyar Nemzeti Arcvonalor the Hungarian National Front, an ultra-rightwing neo-nazi paramilitary organization.

Moscow has been equally active in Italy. Not long ago, Buzzfeed, an American online source, announced that it has recordings of negotiations between Russian businessmen and members of the radical right-wing Lega Nordor Northern League party that took place at the Metropole Hotel. Italy was represented by Gianluca Savoini, close ally and advisor to PM Matteo Salvini. “We want to change Europe,” was how Savoini began the meeting. “The new Europe should be closer to Russia, like it was in the past.” The Russians, in return, proposed a deal where money from the accounts of oil companies would go through a series of intermediary banks to the accounts of Italy’s right wing. The amount of financing was nearly US $65mn. The veracity of the exposure can be assessed variously, given Buzzfeed’s reputation, but the close relations between Salvini and his Lega and Moscow cannot be denied. His anti-European rhetoric completely coincides with the Kremlin narrative about “the end of a unified Europe” or the need to return to cooperation with the Russian Federation. The practical application of these policies can be see in the Italian government’s behavior at the international level in its vote to let Russia back into PACE and at the national level with the recent 24-year sentence handed down against National Guardsman Vitaliy Markiv. But unlike Austria, where the revelation of negotiations raised a wave of protests and led to the resignation of the chancellor and Government, Rome remained unmoved. Lega Nord denies that it has received money from Moscow, while Italy’s law enforcement agencies restricted themselves to calls for Savoini to be questioned.

RELATED ARTICLE: Brian Whitmore: “Putin wants to party like it is 1815”

In other countries, Moscow’s fingerprints can also be found. For instance, one of the main Brexit sponsors, Aaron Banks of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) offered an explanation for the real source of £8mn. Apparently, he was offered a number of lucrative deals for trading in gold and diamonds through the Russian embassy. According to Bild, a German weekly, the right-wing AfD was also paid to sell Russian gold, although the party denies this. Leaders of the Austrian radical right Freedom Party and Vice Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache were forced to resign after a recent scandal involving a video in which he was supposedly discussing with the niece of a Russian oligarch possible government contracts in exchange for Moscow’s support. Links to Russian businesses have been found between MPs in the ultra-right Bulgarian party Attack, the Slovak ultra-right National Party–Our Slovakia and the pro-Russian but central-left Harmony party. One way or another, humans have weaknesses and someone can always be found to take advantage of them. In the end, this is also just one dimension of Russia’s hybrid war against the West.

A sticky web of influence

Which right-wing parties in Europe support Russia

|

Country |

Party name |

Original name |

|

Austria |

Freedom Party of Austria |

Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) |

|

Belgium |

Flemish Interest |

Vlaams Belang |

|

Bulgaria |

Attack |

Атака |

|

Great Britain |

British National Party UK Iindependence Party |

British National Party (BNP) UK Independence Party (UKIP) |

|

Greece |

Golden Dawn |

Χρυσή Αυγή |

|

Hungary |

Jobbik (Movement for a better Hungary) |

Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom |

|

Lithuania |

Order and Justice |

Tvarka ir teisingumas, ТТ |

|

Germany |

Alternative for Germany National Democratic Party of Germany |

Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD) |

|

France |

National Front |

Front National |

|

Italy |

Northern League (The Northern League for the Independence of Padania) The New Force |

Lega Nord per l’Indipendenza della Padania Forza Nuova |

|

Latvia |

Russian Union of Latvia |

Latvijas Krievu savienība (LKS) |

|

Slovakia |

Kotleba Our Slovakia National Party |

Kotleba Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko Slovenská národná strana |

|

Spain |

National Democracy |

Democracia Nacional (DN) |

|

Denmark |

Danish People’s Party |

Dansk Folkeparti (DF) |

|

Czechia |

Workers’ Party for Social Justice |

Dělnická strana sociální spravedlnosti (DSSS) |

|

Poland |

Change Self-defense of the Polish Republic |

Samoobrona Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej Zmiana |

Sources: Alliance for Peace and Freedom, Political Capital, VoteWatch Europe

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook