The pens were on the table in Minsk, Belarus’s capital, for the leaders of France, Germany, Russia and Ukraine to sign a deal to end a year-long war fuelled by Russia and fought by its proxies. But on February 12th, after all-night talks, they were put away. “No good news,” said Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine’s president. Instead there will be a ceasefire from February 15th. A tentative agreement has been reached to withdraw heavy weaponry.

But Russia looks sure to be able to keep open its border with Ukraine and sustain the flow of arms and people. The siege of Debaltseve, a strategic transport hub held by Ukrainian forces, continues. Russia is holding military exercises on its side of the border. Crimea was not even mentioned.

Nearly a quarter-century after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the West faces a greater threat from the East than at any point during the cold war. Even during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, Soviet leaders were constrained by the Politburo and memories of the second world war. Now, according to Russia’s chief propagandist, Dmitry Kiselev, even a decision about the use of nuclear arms “will be taken personally by Mr Putin, who has the undoubted support of the Russian people”. Bluff or not, this reflects the Russian elite’s perception of the West as a threat to the very existence of the Russian state.Meanwhile the IMF has said it will lend Ukraine $17.5 billion to prop up its economy. But Mr Putin seems to be relying on a familiar Russian tactic of exhausting his negotiating counterparts and taking two steps forward, one step back. He is counting on time and endurance to bring the collapse and division of Ukraine and a revision of the post-cold war world order.

In this view Russia did not start the war in Ukraine, but responded to Western aggression. The Maidan uprising and ousting of Viktor Yanukovych as Ukraine’s president were engineered by American special services to move NATO closer to Russia’s borders. Once Mr Yanukovych had gone, American envoys offered Ukraine’s interim government $25 billion to place missile defences on the Russian border, in order to shift the balance of nuclear power towards America. Russia had no choice but to act.

RELATED ARTICLE: How Russian Troops Entered Donbas on August 23

Even without Ukraine, Mr Putin has said, America would have found some other excuse to contain Russia. Ukraine, therefore, was not the cause of Russia’s conflict with the West, but its consequence. Mr Putin’s purpose is not to rebuild the Soviet empire—he knows this is impossible—but to protect Russia’s sovereignty. By this he means its values, the most important of which is a monopoly on state power.

Behind Russia’s confrontation with the West lies a clash of ideas. On one side are human rights, an accountable bureaucracy and democratic elections; on the other an unconstrained state that can sacrifice its citizens’ interests to further its destiny or satisfy its rulers’ greed. Both under communism and before it, the Russian state acquired religious attributes. It is this sacred state which is under threat.

Mr Putin sits at its apex. “No Putin—no Russia,” a deputy chief of staff said recently. His former KGB colleagues—the Committee of State Security—are its guardians, servants and priests, and entitled to its riches. Theirs is not a job, but an elite and hereditary calling. Expropriating a private firm’s assets to benefit a state firm is therefore not an act of corruption.

When thousands of Ukrainians took to the streets demanding a Western-European way of life, the Kremlin saw this as a threat to its model of governance. Alexander Prokhanov, a nationalist writer who backs Russia’s war in Ukraine, compares European civilisation to a magnet attracting Ukraine and Russia. Destabilising Ukraine is not enough to counter that force: the magnet itself must be neutralised.

Russia feels threatened not by any individual European state, but by the European Union and NATO, which it regards as expansionist. It sees them as “occupied” by America, which seeks to exploit Western values to gain influence over the rest of the world. America “wants to freeze the order established after the Soviet collapse and remain an absolute leader, thinking it can do whatever it likes, while others can do only what is in that leader’s interests,” Mr Putin said recently. “Maybe some want to live in a semi-occupied state, but we do not.”

Russia has taken to arguing that it is not fighting Ukraine, but America in Ukraine. The Ukrainian army is just a foreign legion of NATO, and American soldiers are killing Russian proxies in the Donbas. Anti-Americanism is not only the reason for war and the main pillar of state power, but also an ideology that Russia is trying to export to Europe, as it once exported communism.

Anti-Westernism has been dressed not in communist clothes, but in imperial and even clerical ones (see article). “We see how many Euro-Atlantic countries are in effect turning away from their roots, including their Christian values,” said Mr Putin in 2013. Russia, by contrast, “has always been a state civilisation held together by the Russian people, the Russian language, Russian culture and the Russian Orthodox church.” The Donbas rebels are fighting not only the Ukrainian army, but against a corrupt Western way of life in order to defend Russia’s distinct world view.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Origins of Donetsk Separatism

Mistaken hopes

Many in the West equate the end of communism with the end of the cold war. In fact, by the time the Soviet Union fell apart, Marxism-Leninism was long dead. Stalin replaced the ideals of internationalism, equality and social justice that the Bolsheviks had proclaimed in 1917 with imperialism and state dominance over all spheres of life. Mikhail Gorbachev’s revolution consisted not in damping down Marxism but in proclaiming the supremacy of universal human values over the state, opening up Russia to the West.

Nationalists, Stalinists, communists and monarchists united against Mr Gorbachev. Anti-Americanism had brought Stalinists and nationalists within the Communist Party closer together. When communism collapsed they united against Boris Yeltsin and his attempts to make Russia “normal”, by which he meant a Western-style free-market democracy.

By 1993, when members of this coalition were ejected by pro-Yeltsin forces from the parliament building they had occupied in Moscow, they seemed defeated. Yet nationalism has resurfaced. Those who fought Yeltsin and his ideas were active in the annexation of Crimea and are involved in the war in south-east Ukraine. Alexander Borodai, the first “prime minister” of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic, who fought with anti-Yeltsin forces, hails Mr Putin as the leader of the nationalist movement in Russia today.

Yet for a few years after Mr Putin came to power he built close relations with NATO. In his first two presidential terms, rising living standards helped buy acceptance of his monopoly on state power and reliance on ex-KGB men; now that the economy is shrinking, the threat of war is needed to legitimise his rule. He forged his alliance with Orthodox nationalists only during mass street protests by Westernised liberals in 2012, when he returned to the Kremlin. Instead of tear gas, he has used nationalist, imperialist ideas, culminating in the annexation of Crimea and the slow subjugation of south-east Ukraine.

Hard power and soft

Mr Putin’s preferred method is “hybrid warfare”: a blend of hard and soft power. A combination of instruments, some military and some non-military, choreographed to surprise, confuse and wear down an opponent, hybrid warfare is ambiguous in both source and intent, making it hard for multinational bodies such as NATO and the EU to craft a response. But without the ability to apply hard power, Russia’s version of soft power would achieve little. Russia “has invested heavily in defence,” says NATO’s new secretary-general, a former Norwegian prime minister, Jens Stoltenberg. “It has shown it can deploy forces at very short notice…above all, it has shown a willingness to use force.”

Mr Putin drew two lessons from his brief war in Georgia in 2008. The first was that Russia could deploy hard power in countries that had been in the Soviet Union and were outside NATO with little risk of the West responding with force. The second, after a slapdash campaign, was that Russia’s armed forces needed to be reformed. Military modernisation became a personal mission to redress “humiliations” visited by an “overweening” West on Russia since the cold war ended.

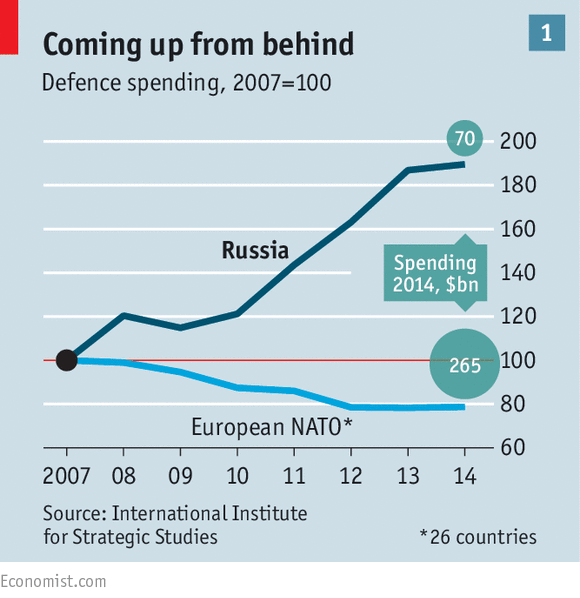

According to IHS Jane’s, a defence consultancy, by next year Russia’s defence spending will have tripled in nominal terms since 2007, and it will be halfway through a ten-year, 20 trillion rouble ($300 billion) programme to modernise its weapons. New types of missiles, bombers and submarines are being readied for deployment over the next few years. Spending on defence and security is expected to climb by 30% this year and swallow more than a third of the federal budget.

As well as money for combat aircraft, helicopters, armoured vehicles and air-defence systems, about a third of the budget has been earmarked to overhaul Russia’s nuclear forces. A revised military doctrine signed by Mr Putin in December identified “reinforcement of NATO’s offensive capacities directly on Russia’s borders, and measures taken to deploy a global anti-missile defence system” in central Europe as the greatest threats Russia faces.

In itself, that may not be cause for alarm in the West. Russian nuclear doctrine has changed little since 2010, when the bar for first use was slightly raised to situations in which “the very existence of the state is under threat”. That may reflect growing confidence in Russia’s conventional forces. But Mr Putin is fond of saying that nobody should try to shove Russia around when it has one of the world’s biggest nuclear arsenals. Mr Kiselev puts it even more bluntly: “During the years of romanticism [ie, detente], the Soviet Union undertook not to use nuclear weapons first. Modern Russian doctrine does not. The illusions are gone.”

Mr Putin still appears wedded to a strategy he conceived in 2000: threatening a limited nuclear strike to force an opponent (ie, America and its NATO allies) to withdraw from a conflict in which Russia has an important stake, such as in Georgia or Ukraine. Nearly all its large-scale military exercises in the past decade have featured simulations of limited nuclear strikes, including one on Warsaw.

Mr Putin has also been streamlining his armed forces, with the army recruiting 60,000 contract soldiers each year. Professionals now make up 30% of the force. Conscripts may bulk up the numbers, but for the kind of complex, limited wars Mr Putin wants to be able to win, they are pretty useless. Ordinary contract soldiers are also still a long way behind special forces such as the GRU Spetsnaz (the “little green men” who went into Crimea without military insignia) and the elite airborne VDV troops, but they are catching up.

RELATED ARTICLE: Crimean Anchor: The rationale behind transferring the peninsula to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954

Boots on the ground

South-east Ukraine shows the new model army at work. Spetsnaz units first trained the Kremlin-backed separatist rebels in tactics and the handling of sophisticated Russian weapons. But when the Ukrainian government began to make headway in early summer, Russia had regular forces near the border to provide a calibrated (and still relatively covert) response.

It is hard to tell how many Russian troops have seen action in Ukraine, as their vehicles and uniforms carry no identifiers. But around 4,000 were sent to relieve Luhansk and Donetsk while threatening the coastal city of Mariupol—enough to convince Mr Poroshenko to draw his troops back. Since November a new build-up of Russian forces has been under way. Ukrainian military intelligence reckons there may be 9,000 in their country (NATO has given no estimate). Another 50,000 are on the Russian side of the border.

Despite Mr Putin’s claim last year that he could “take Kiev in two weeks” if he wanted, a full-scale invasion and subsequent occupation is beyond Russia. But a Russian-controlled mini-state, Novorossiya, similar to Abkhazia and Transdniestria, could be more or less economically sustainable. And it would end Ukraine’s hopes of ever regaining sovereignty over its territory other than on Russian terms, which would undoubtedly include staying out of the EU and NATO. Not a bad outcome for Mr Putin, and within reach with the hard power he controls.

The big fear for NATO is that Mr Putin turns his hybrid warfare against a member country. Particularly at risk are the Baltic states—Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania—two of which have large Russian-speaking minorities. In January Anders Fogh Rasmussen, NATO’s previous secretary-general, said there was a “high probability” that Mr Putin would test NATO’s Article 5, which regards an attack on any member as an attack on all—though “he will be defeated” if he does so.

RELATED ARTICLE: Russian Military Bases around NATO borders and in Central Asia

A pattern of provocation has been established that includes a big increase in the number of close encounters involving Russian aircraft and naval vessels, and snap exercises by Russian forces close to NATO’s northern and eastern borders. Last year NATO planes carried out more than 400 intercepts of Russian aircraft. More than 150 were by the alliance’s beefed-up Baltic air-policing mission—four times as many as in 2013. In the first nine months of the year, 68 “hot” identifications and interdictions occurred along the Lithuanian border alone. Latvia recorded more than 150 incidents of Russian planes entering its airspace.

There have also been at least two near-misses between Russian military aircraft and Swedish airliners. This is dangerous stuff: Russian pilots do not file flight plans. They fly with transponders switched off, which makes them invisible to civil radar. On January 28th two Russian, possibly nuclear-armed, strategic bombers flew down the English Channel, causing havoc to commercial aviation. Such behaviour is intended to test Western air defences, and was last seen in the cold war. Mr Stoltenberg calls it “risky and unjustified”.

Since 2013, when Russia restarted large-scale snap military exercises, at least eight have been held. In December the Kremlin ordered one in Kaliningrad, an exclave that borders Lithuania and Poland, both NATO members. It mobilised 9,000 soldiers, more than 55 navy ships and every type of military aircraft. “This pattern of behaviour can be used to hide intent,” says General Philip Breedlove, NATO’s most senior commander. “What is it masking? What is it conditioning us for?”

A huge problem for NATO is that most of what Russia might attempt will be below the radar of traditional collective defence. According to Mr Stoltenberg, deciding whether an Article 5 attack has taken place means both recognising what is going on and knowing who is behind it. “We need more intelligence and better situational awareness,” he says; but adds that NATO allies accept that if the arrival of little green men can be attributed “to an aggressor nation, it is an Article 5 action and then all the assets of NATO come to bear.”

For all the rhetoric of the cold war, the Soviet Union and America had been allies and winners in the second world war and felt a certain respect for each other. The Politburo suffered from no feelings of inferiority. In contrast, Mr Putin and his KGB men came out of the cold war as losers. What troubles Mr Stoltenberg greatly about Mr Putin’s new, angry Russia is that it is harder to deal with than the old Soviet Union. As a Norwegian, used to sharing an Arctic border with Russia, he says that “even during the coldest period of the cold war we were able to have a pragmatic conversation with them on many security issues”. Russia had “an interest in stability” then, “but not now”.

Meddling and perverting

Destabilisation is also being achieved in less military ways. Wielding power or gaining influence abroad—through antiestablishment political parties, disgruntled minority groups, media outlets, environmental activists, supporters in business, propagandist “think-tanks”, and others—has become part of the Kremlin’s hybrid-war strategy. This perversion of “soft power” is seen by Moscow as a vital complement to military engagement.

Certainly Russia is not alone in abusing soft power. The American government’s aid agency, USAID, has planted tweets in Cuba and the Middle East to foster dissent. And Mr Putin has hinted that Russia needs to fight this way because America and others are already doing so, through “pseudo-NGOs”, CNN and human-rights groups.

At home Russian media, which are mostly state-controlled, churn out lies and conspiracy theories. Abroad, the main conduit for the Kremlin’s world view is RT, a TV channel set up in 2005 to promote a positive view of Russia that now focuses on making the West look bad. It uses Western voices: far-left anti-globalists, far-right nationalists and disillusioned individuals. It broadcasts in English, Arabic and Spanish and is planning German- and French-language channels. It claims to reach 700m people worldwide and 2.7m hotel rooms. Though it is not a complete farce, it has broadcast a string of false stories, such as one speculating that America was behind the Ebola epidemic in west Africa.

RELATED ARTICLE: Donetsk-born historian and sociologist Oksana Mikheyeva:“We must drag people out of the media coma”

The West’s willingness to shelter Russian money, some of it gained corruptly, demoralises the Russian opposition while making the West more dependent on the Kremlin. Russian money has had a poisonous effect closer to home, too. Russia wields soft power in the Baltics partly through its “compatriots policy”, which entails financial support for Russian-speaking minorities abroad.The Kremlin is also a sophisticated user of the internet and social media. It employs hundreds of “trolls” to garrison the comment sections and Twitter feeds of the West. The point is not so much to promote the Kremlin’s views, but to denigrate opposition figures, and foreign governments and institutions, and to sow fear and confusion. Vast sums have been thrown at public-relations and lobbying firms to improve Russia’s image abroad—among them Ketchum, based in New York, which helped place an op-ed by Mr Putin in the New York Times. And it can rely on some of its corporate partners to lobby against policies that would hurt Russian business.

Mr Putin’s most devious strategy, however, is to destabilise the EU through fringe political parties. Russia’s approach to ideology is fluid: it supports both far-left and far-right groups. As Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss put it in “The menace of unreality”, a paper on Russian soft power: “The aim is to exacerbate divides [in the West] and create an echo-chamber of Kremlin support.”

Disruptive politics

Far-right groups are seduced by the idea of Moscow as a counterweight to the EU, and by its law-and-order policies. Its stance on homosexuality and promotion of “traditional” moral values appeal to religious conservatives. The far left likes the talk of fighting American hegemony. Russia’s most surprising allies, however, are probably Europe’s Greens. They are opposed to shale-gas fracking and nuclear power—as is Moscow, because both promise to lessen Europe’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels. Mr Rasmussen has accused Russia of “sophisticated” manipulation of information to hobble fracking in Europe, though without producing concrete evidence.

There is circumstantial evidence in Bulgaria, which in 2012 cancelled a permit for Chevron to explore for shale gas after anti-fracking protests. Some saw Russia’s hand in these, possibly to punish the pro-European government of the time, which sought to reduce its reliance on Russian energy (Gazprom, Russia’s state-controlled gas giant, supplies 90% of Bulgaria’s gas).

RELATED ARTICLE: New Energy Addiction

Previously, Bulgaria had been expected to transport Russian oil through its planned South Stream pipeline, and its parliament had approved a bill that would have exempted the project from awkward EU rules. Much of it had been written by Gazprom, and the construction contract was to go to a firm owned by Gennady Timchenko, an oligarch now under Western sanctions. Gazprom offered to finance the pipeline and to sponsor a Bulgarian football team. The energy minister at the time later claimed he had been offered bribes by a Russian envoy to smooth the project’s passage. Though European opposition means it has now been scrapped, the episode shows the methods Moscow uses to protect its economic interests.

In all this Mr Putin is evidently acting not only for Russia’s sake, but for his own. Mr Borodai, the rebel ideologue in Donetsk, says that if necessary the Russian volunteers who are fighting today in Donbas will tomorrow defend their president on the streets of Moscow. Yet, although Mr Putin may believe he is using nationalists, the nationalists believe they are using him to consolidate their power. What they aspire to, with or without Mr Putin, is that Russians rally behind the nationalist state and their leader to take on Western liberalism. This is not a conflict that could have been resolved in Minsk.

© 2011 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved