The latest opinion polls in Russia show rapidly increasingly support for Vladimir Putin’s actions and his improving chances of winning a hypothetical presidential election against the backdrop of Russia’s aggression in the Crimea. According to the Obshchestvennoye mnenie (Public Opinion) Foundation, 53% of Russians, up by five percentage points in just a week’s time between late February and early March, support him for president.

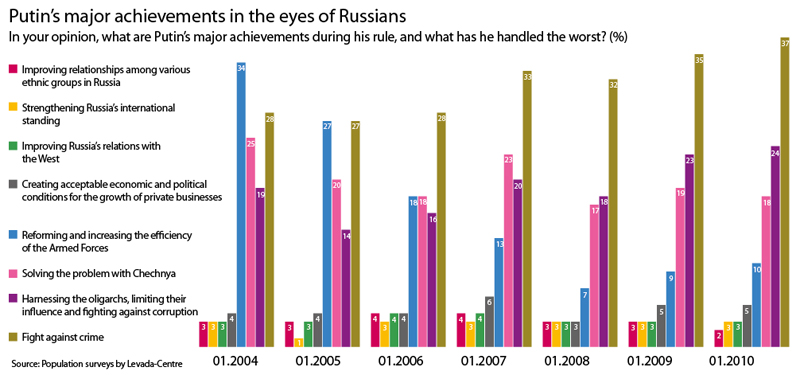

This fact again draws attention to a characteristic regularity in Putin’s Russia in the past 15 years. Over many years, population surveys have shown that the majority of Russian citizens view Putin precisely as a power imperialist capable of “rubbing them out in the outhouse”, meaning the Chechens, Georgians and now Ukrainians. Meanwhile, he has never been associated with any positive developments in the socioeconomic sphere, improving moral and psychological climate or easing interethnic relations in Russia’s multinational federation. Nor has he chalked up any special international successes (see Putin’s major achievements in the eyes of Russians).

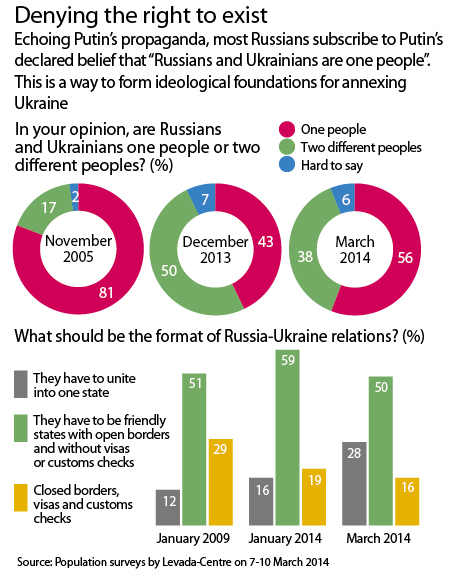

In order to win and maintain support among the Russians who have nostalgia for imperial might, Putin has shown his willingness to start bloody wars and constantly seek “external enemies” since he rose to power.

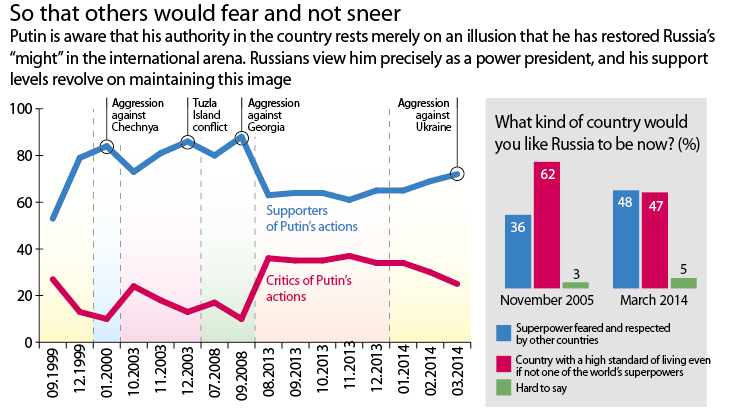

Poll data collected by Levada Centre since the late 1990s reveals that, starting from the Chechen campaign in 1999-2000, Putin’s support levels have always skyrocketed in conflict situations with the neighbouring post-Soviet countries: the Tuzla Island incident with Ukraine, the disruption of NATO action plans for Ukraine and Georgia in spring 2008, Russia’s aggression against Georgia in August 2008, the trade blockade of Ukraine in August 2013, the derailing of the Association Agreement with the EU for Ukraine in 2013 and, finally, invasion of the Crimea. Putin’s popularity ratings slumped between these crisis points (see So that others would fear and not sneer).

In March 2014, the proportion of the respondents who view contemporary Russia as a “superpower” has reached the highest value in the history of such surveys: 48% want to see Russia as a “superpower respected and feared”; two-thirds believe their country is already playing a decisive (11% ) or quite important (56% ) part in solving international problems.

It is in this context that the reasoning behind Putin’s actions in the Crimea should be interpreted. From a purely practical viewpoint, the annexation of the peninsula (or even keeping it in a condition similar to that of Transnistria) does not give Russia any significant advantages. On the contrary, it creates colossal problems, threatening financial and economic losses for the country and the elites close to the Kremlin, fuelling anti-Russian sentiments across the world, including in the European capitals which were loyal to Moscow until recently, and precipitating the confrontation with the USA. This is not to mention next-to-zero chances of any pro-Russian projects rising to power in Ukraine, which seems to be what Putin is fighting for. With the annexation of the Crimea by Russia, Ukraine’s electoral field has lost regions in which up to 80-90% of voters favoured pro-Russian forces.

Lightningrod.ua

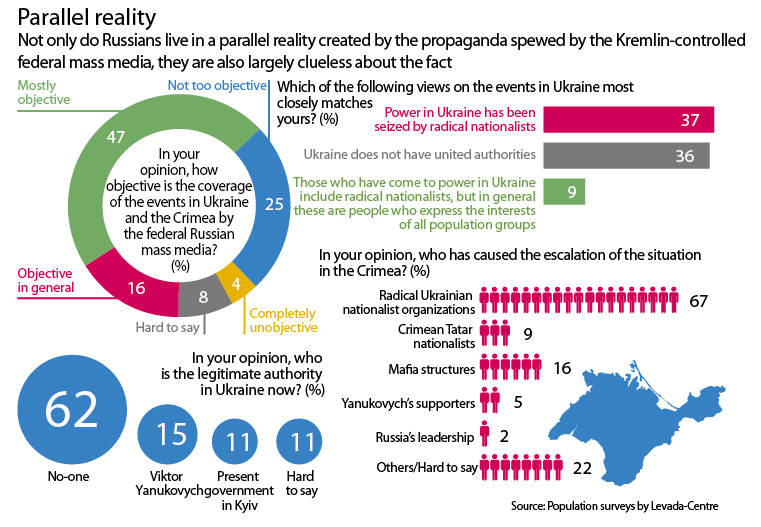

Even with the Russian mass media being completely controlled by the government, it is much harder to deceive Russians about the situation inside the Russian Federation, particularly with regard to corruption, slumping socioeconomic growth and the plummeting standard of living, than to lie about what happens abroad – people tend to follow stereotypical notions. This is what Putin’s propaganda exploits as it totally dominates the federal TV channels, which shape the attitudes of most Russians. Its extensive influence became vividly obvious when Russians sharply changed their attitude to Ukrainians in 2010. A Levada-Centre survey showed that after media coverage of the developments in Ukraine was modified, the proportion of sympathetic respondents grew from 29% in 2009 to 52% in 2010, while the share of negatively-minded Russians dropped from 62 to 36% . Russia’s aggression in Ukraine is indeed diverting Russians’ attention from the problems in their own country. This has been clearly demonstrated by recent population surveys. Levada-Centre has found that the share of Russians who are watching the events in Ukraine very or fairly closely has grown from 25% in December 2013 to 60% in March 2014, while the number of those who do not keep track or have not heard of the developments has fallen from 35 to 8% over the same period.

The war will be used as an excuse to explain the steep devaluation of the rouble, the falloff in the standard of living (Russians depend on imported consumer goods to a much greater extent than Ukrainians do) and the worsening economic crisis. For example, GDP growth rates fell from 4.3-4.5% in 2010-11 to 1.3% in 2013 and may hover around zero in 2014, even without factoring in the possible negative consequences of Western sanctions. Russia’s ex-Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin has said that the sanctions against Russia over the situation with Ukraine may affect Russia’s economy more seriously than the Russian government expects.

READ ALSO: Putin’s Expensive Victory

Putin’s aggressive policy seems to have an equally important goal of justifying a rapid increase in defence spending with the hope of boosting the economy, because the potential for energy-driven growth is essentially exhausted. Defence spending is growing by leaps and bounds. In November 2013, Putin dramatically announced: “The overall amount of allocations for defence contracts by the state has exceeded 1.3 trillion roubles in 2013. This is one and a half times more – not some per cent but one and a half times more – than in the previous year.” The total federal military expenses (2.1 trillion roubles in 2013) are already comparable to what Russia spends on education or medicine at all levels. You cannot increase defence spending so fast without a real picture of a “big war”.

The price of Putin’s rating-boosting games

However, Russia is paying a steep price for the Putin Administration’s bull-in-a-china-shop policy pursued for the sake of shoring up popular support –the country is losing allies, instead surrounding itself with a widening circle of enemies. This once again confirms a well-known truth: Russia can never have allies along its borders, only vassals or enemies. In the present crisis, even Russia’s partners in the Customs Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization are not acting like allies, for each of these countries understands thatit may be the next target after Ukraine. Belarus may be annexed, while Kazakhstan has a risk of losing, at the least, its northern and north-eastern regions, which are dominated by Russian-speaking descendants of settlers from the European part of Russia. Putin’s invasion was supported by the semi-overthrown Assad regime, which controls only a small part of its own country, and North Korea, humiliating and symbolic as it is. They were joined by the puppet regimes in Russia-occupied territories – Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria.

The West is highly likely to ratchet up its sanctions. In this case, Russia may be forced to cooperate with the rest of the world along the lines of “oil and gas in exchange for food”, as was the case with the Saddam Hussein regime at one point. According to the Russian Federal State Statistics Service, energy resources accounted for 70.6% (US $371.8bn) of Russia’s exports in 2013. Losing even a third of these revenues may give Russia’s economy and its federal budget a severe shock. Nearly 60% of Russia’s foreign trade is with the EU, US, other G7 countries (Canada and Japan) which have condemned Russia’s actions in the Crimea and Turkey.

By feeding its population dubious “circuses” via controlled mass media outlets in an artificially created information vacuum, the Russian government may be doing just enough to make people ignore increasing problems with “bread” provision, but this policy is unsustainable in the long term. This is especially true if what Russia is faced with is not a brief “express reaction” (something the Kremlin is hoping for) but truly prolonged, systemic opposition by the wealthiest powers. Naturally, sanctions may provoke the Kremlin into more aggression, such as an attempt to confiscate the assets of Western investors or direct aggression against Ukraine.

However, in the present situation this scenario may lead to truly catastrophic consequences for Russia, including US and NATO military intervention. According to some sources, US and NATO leaders are trying hard to avoid making direct public threats in order not to “humiliate Russia”. However, they have increasingly given to understand that they are not “ruling out any scenarios”. For example, Senior Advisor to the US President Dan Pfeiffer has said that supporting the new Ukrainian government “by all possible means” is a priority for the Obama Administration.

If Western pressure on Russia is consolidated and eventually reaches maximum intensity, this may well deliver a powerful blow against Putin and possibly even lead to a putsch in the Russian government. This brings to mind the Crimean War of 1853-56. Back then, the Russian Empire, the “gendarme of Europe”, looked to score a victory over the Ottoman Empire, an apparently much weaker enemy, but it turned into a shameful defeat when Russia was faced with a united front of Europe’s leading powers. This fiasco led to serious internal reform in Russia, something it also badly lacks today.

READ ALSO: Derussification

This time around, though, the war may continue without the use of military force. Moreover, the well-known cyclic nature of Russian history may thwart Putin’s plans. In Russia, cruel autocrats alternated with relatively liberal reformers: Stalin, then Khrushchev and Brezhnev; then, briefly, Andropov and Chernenko; and again liberal Gorbachev and Yeltsin. Now, Putin has been ruling the country for 15 years.