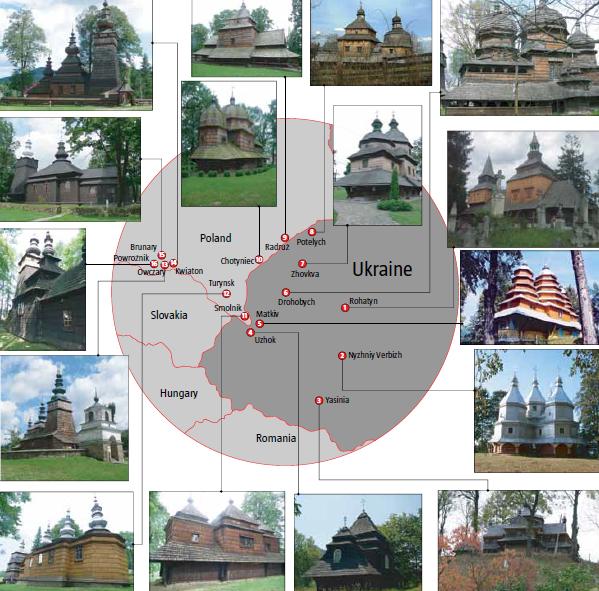

This year, UNESCO added 16 wooden churches to its List of World Heritage Sites—eight in Ukraine, eight in Poland. Lviv Oblast in Ukraine and Podkarpackie and Lublin provinces in Poland have four each; Ivano-Frankivsk and Zakarpattia Oblasts in Ukraine have two each. If you have enough time, you can see many other masterpieces of sacred wooden architecture along the way. Unfortunately, not all of Ukraine’s antique wooden churches made it onto UNESCO’s list.

Before applying to UNESCO, Ukrainian members of the initiative committee examined hundreds of wooden churches along the Ukrainian-Polish border, choosing eight that met UNESCO’s criteria: they are unique, well preserved, open to visitors, and their congregations support their addition to the list. Overall, most of the wooden churches designated as architectural heritage sites in Ukraine are located in the west of the country. Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk and Zakarpattia Oblasts alone are home to 1,089 of Ukraine’s 2,353 wooden churches.

Ivano-Frankivsk

We begin our tour in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast with its 462 wooden churches qualified as architectural heritage sites. The first town we suggest visiting is Rohatyn (1). It was the birthplace of Nastya Lisovska, the legendary Roxelana or Hürrem Haseki Sultan – the legal wife of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. The local church is one of the oldest preserved wooden churches in Ukraine, though its precise age is a matter of scientific controversy. According to popular opinion, it was built in the early 17th century. The official date, however, is 1598: the local priest Ipolyt Dzerovych found the date carved on the northern wall of the central zrub – a solid-timber section. The shrine has one of the oldest and most beautiful Renaissance-Baroque iconostases in Ukraine dating back to 1650. The church and its iconostasis attained their status as works of art at the time of Austro-Hungarian rule, when the shrine was first listed as an architectural heritage site. In 1963, it was added to a list of national historical sites for a second time. In the 1980s, it was restored by Ivan Mohytych, a top Ukrainian expert. Today, the church acts as a branch of the Ivano-Frankivsk art museum while also serving religious functions. The National Bank issued a memorial coin depicting the church in 2009.

The village of Nyzhniy Verbizh (2) in Kolomyia County is known as a crossroads of four mountain rivers, including the mighty and turbulent Prut. It is also the birthplace of Hryhoriy Semeniuk, an ally of legendary Carpathian outlaw Oleksa Dovbush – a folk hero often compared to Robin Hood. Local lore claims that Semeniuk began construction of the shrine in his village. It is unique for its five domes built in the traditional Hutsul[1] style and covered with engraved tin. The church was actually built in 1808 but the interior still contains icons from the late 18th century. Regular services are still held in the church today.

Zakarpattia

We move westward through Zakarpattia Oblast, home to 110 preserved wooden churches recognized as architectural heritage sites. One is the Church of Ascension or Strukiv Church in the village of Yasinia (3). Local lore claims that the village’s founder, Ivan Struk, built the church out of gratitude to God for saving his sheep in a storm. The modern Church of the Ascension, however, dates back to 1824. It is one of the best examples of sacred Hustul architecture. Inside, there is an iconostasis from the late 18th century and a number of 17th-century icons. Perhaps the local lore is true after all…

The village of Uzhok (4) in Velykyi Bereznyi County is on the border of Zakarpattia Oblast near the Uzhok Pass where the river Uzh begins. The local Church of St. Michael the Archangel is one of the county’s symbols and a popular subject for painters. It was built in 1745 in the Boyko[2] style. Similar churches are widespread in mountainous parts of Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts. The Uzhok shrine stands atop a hill and fits harmoniously with the surrounding landscape.

Lviv

Across the Uzhok Pass is Lviv Oblast, home to 517 of Ukraine’s wooden churches. The first one that we will visit is in the village of Matkiv (5) in Turka County, several kilometres from the border with Zakarpattia. The most beautiful element of this village at the source of the Stryi River is the wooden Church of the Holy Mother of God re-consecrated in honour of St. Demetrius. Like the church in Uzhok, it is in the Boyko style, although it differs from Zakarpattian Boyko architecture. Built in 1838, the church houses an iconostasis from the 1840s.

Drohobych (6) is the largest town in this list, hosting a few dozen architectural sites. St. George’s Church stands out in particular. In 1656, it was moved from the village of Nadiyiv, now in Dolyna County, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. The chapel of the Introduction of the Blessed Virgin Mary built over the choir balcony makes the shrine’s structure unique.

Zhovkva County (7) in Lviv Oblast has two churches on the UNESCO list. One is the Holy Trinity Church in Zhovkva. Once a residence of the Polish kings Sobieski, the town will probably end up on the UNESCO list someday as well. Its church was originally built in 1601 but was destroyed in a fire, so the modern building dates back to 1720. It contains 18th-century murals and a five-layer Baroque iconostasis created by the masters of the Zhovkva Painting and Carving School under Ivan Rutkovych. Today, the building acts as a church and museum.

Potelych, a village on the Ukrainian-Polish border, hosts several architectural sites and a German military cemetery. The most interesting building here is the Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit. Built in 1502 on the site of the former Church of Boris and Glib, its construction was financed with donations from local potters. In the 1970s, skilled Lviv masters Ivan Mohytych and Bohdan Kindzelskyi restored it.

POLAND

Once your tour of Ukrainian wooden churches is over in Potelyczi (8), cross the border at Rava-Ruska to the border village of Hrebenne. Very close to the border is the Polish village of Radruż (9) in Lubaczów Powiat (County), Podkarpackie (Subcarpathian) Voivodeship. Built in 1583, its interior still contains icons from the late 17th century. Some are at the museum in the Łańcut castle. The church now acts as a museum.

Another wooden shrine near the Krakovets-Korchova border crossing is the Church of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the village of Chotyniec (10). Until World War II it was a large village mostly inhabited by Ukrainians. Today it is part of Jaroslaw Powiat (County) in the Podkarpackie (Subcarpathian) Voivodeship. The main architectural site in this village is a church built in the Halychyna style in around 1600. The shrine still houses an 18th-century iconostasis probably dating back to 1671.

Smolnik (11), a village in Podkarpackie Voivodeship, was part of the Lemko-Rusyn Republic[3] in the years of the national liberation struggle. The Republic existed from November 4, 1918, through January 23, 1919, and ended up part of Poland after a swap of territories in 1951. The functional Church of St. Michael the Archangel located there was built in 1791. This is the only three-domed Boyko church preserved on the territory of Poland. It is also interesting for its unique icon of the Assumption of the Holy Mother of God dating back to 1748 and its 18th-century murals portraying prophets from the Old Testament.

The village of Turynsk (12), a bit west of Smolnik, in Sanok Powiat, is home to another Church of St. Michael the Archangel. It is in the Lemko style, since many Ukrainian Lemkos used to live in the neighbourhood. Built in the early 19th century, it was rebuilt and expanded many times. Today, it is a functioning Polish Autocephalous Orthodox church. It also hosts unique 19th-century icons by Joseph Bukowczyk.

READ ALSO: Newcomers to the UNESCO World Heritage List

Four more wooden churches are located near each other in the Malopolska Voivodeship near the Polish-Slovak border (13, 14, 15, 16). Gorlice Powiat has the St. Paraskevia Church built in 1811. It is considered to be the best-preserved church in the Western Lemko style. Inside is a 1904 iconostasis by Mykhailo Bohdanovskyi portraying saintly Kyivan Rus leaders Volodymyr and Olga.

Another piece of Western Lemko architecture is the Protection of the Blessed Virgin Church in the village of Owczary. Built in 1710, its style has many Baroque elements, including an iconostasis painted in 1712 by artist Ivan Medytskyi.

Our tour of wooden churches on the Polish-Ukrainian border ends in Powroźnik, a village in Malopolska (Lesser Poland) Voivodeship where the Church of St. James the Less towers. This Western Lemko church was built in 1600 but changed considerably after being relocated in 1814. It has unique murals by Pavlo Radynskyi dating back to 1607 – older than all other wooden churches in the region.

[1] Hutsuls are an ethno-cultural group of highlanders inhabiting the Ukrainian and Romanian Carpathians. They once spoke a distinct dialect of Ukrainian, but standardized education introduced by Stalin nearly wiped it out. All three Carpathian ethnic groups – Hutsuls, Boykos and Lemkos – have very distinct cultures and arts that are quite different from the rest of Ukraine. This has mostly survived in the Ukrainian Carpathians, especially in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. Typical Hutsul churches were built in the shape of the cross with three or five flat layered domes.

[2] Boykos are an ethnic group that traditionally lived in the Carpathians. Today, most register themselves as Ukrainians and live in Ukraine or Poland. The wooden church architecture of the Boyko region typically has a three-domed design with the domes arranged in one line, the middle one larger than the others.

[3] Lemkos are an ethnic group of Ukrainian highlanders who lived in the Carpathian regions that are now part of Poland. They spoke their own dialect of Ukrainian. The community was dispersed during forced resettlement in Operation Vistula in 1939. Their churches traditionally feature a dominating belfry tower over the western section, while the middle and eastern towers are each lower than the one preceding it, creating a dynamic composition.