The Price of Sex, a documentary by Bulgarian-born American journalist Mimi Chakarova, is based on a decade-long investigation of human trafficking and forced prostitution in Eastern Europe. Prolonged exhaustive efforts, including the undercover infiltration of human trafficking and illegal sex industries resulted in this shocking film.

UW: What difficulties did you face while investigating the people involved in this underground business, including pimps and victims of coerced prostitution? How much of a challenge was it to get the information you wanted?

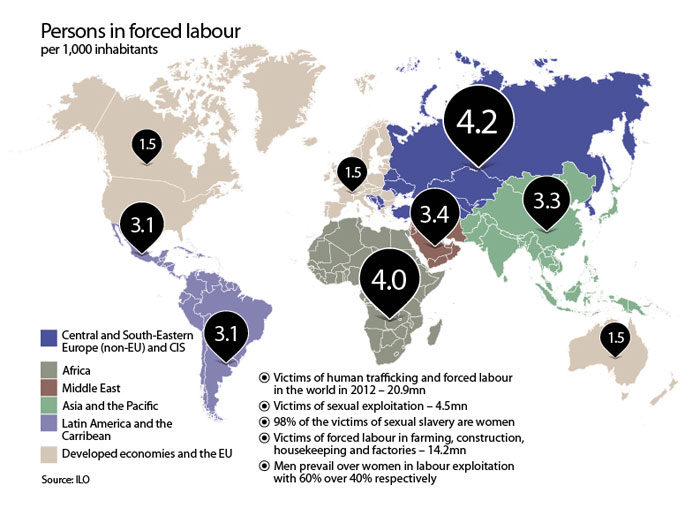

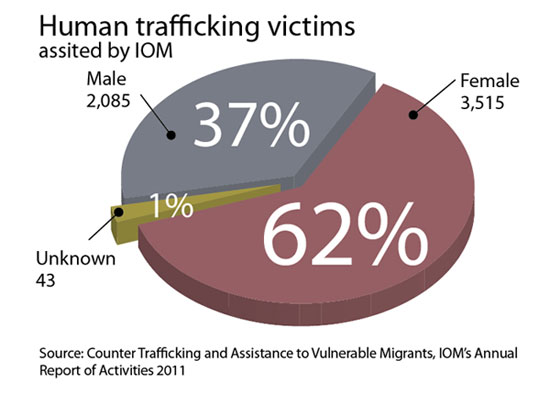

Sometimes I thought it was next to impossible to get the information I needed for my investigation. Initially, I had to act without having any idea about how difficult it would be to find the victims of human trafficking and sex exploitation. This sort of investigation deals with an underground, shadowy business. Often, people are not willing to talk about the issue. The girls don’t like to tell people what they have been through. Those who sold and supervised them refuse to talk about what they do. Whenever you ask about the trafficking of women, you have to realize that the criminals transporting and selling people are also involved in other businesses, such as drug and arms trafficking. Drugs, weapons, people – you can buy and sell it all. It’s not just women. Men are also sold as slave labour. All information about this business and everything that surrounds it is well hidden.

Remember, this involves huge sums of money. The local officials who benefit from the trafficking of women in one way or another also prefer to keep their mouths shut for as long as possible. The victims of coerced prostitution are often psychologically crushed when they realize they will have to work as prostitutes, not as cleaning ladies, waitresses or plant employees as they were promised. Pimps take photos or videos of them, sometimes being gang raped, to control and blackmail the women, promising to send the photos or videos to their families if they try to run away. So videotaping was not always the best way to collect the material: as soon as I took my camera out, most girls refused to continue the conversation. I realized that I would never manage to take any photos that way. When I started asking for permission to take pictures, the answer depended on how painful the girls’ individual experience was.

I asked the victims many times why they did not go to the police for help. But the police often turn out to be working with the criminals despite their duty to protect the victims, so they are not willing to speak either. In fact, police officers themselves often rape trafficked girls. And the girls often saw permanent clients of local brothels at police stations. They called the pimps to come and get the runaway girls back.

The media rarely cover all this. If you asked me what journalistic investigations I would do if I had the time and money, my priority would be corruption within the NGOs that deal with trafficked women. My second priority would be to show how weapons, drugs, women and men are trafficked to destination countries as forced labourers. This is the labour slavery of the 21st century.

READ ALSO: Elusive Slave Owners

UW: What is the common public opinion of human trafficking and sex slavery in the Eastern European states you covered in your investigation? How intolerant are people toward the victims – especially female – of the illegal sex industry?

I’ve noticed negative stereotypes about women who were in slave trafficking or coercive prostitution. They are often scolded as whores after they return home. Sometimes girls feel pressure from neighbours or even parents for not earning any income while prostitution seems like something that can make them somewhat more helpful. I’ve seen this many times. I can’t tell you how relatives insult these girls and how they treat them. Do you think this attitude encourages them to stay at home?

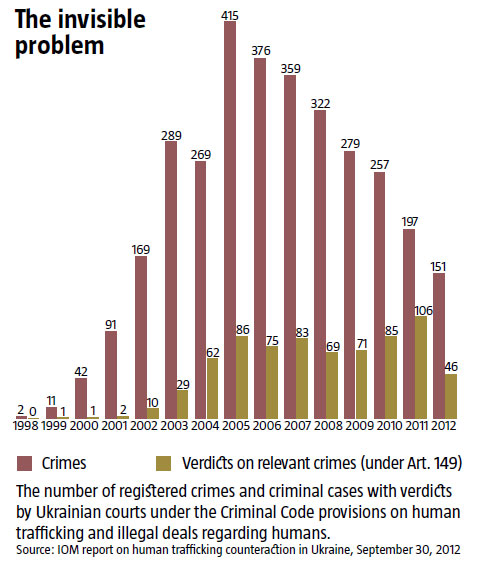

Human trafficking is mostly the case in a corrupt judiciary where slave traffickers can bribe judges, get out of jail quickly and continue their dirty business. As a result, the girls end up stuck in the system; they have nowhere to run or hide.

UW: What does it mean to be sold into slavery today? How difficult is it for the victims of labour and sex slavery to return to normal lives in society?

The fastest way to crush the human spirit is to sell a person into slavery. It destroys the identity and undermines every value the person used to have and believe in. This is especially true with girls. Say, a girl is sold at the age of 12, and she is 23-24 now. Prostitution is all she knows. So, what kind of relationship can she build with the world and the people surrounding her? Her entire life experience is that of a slave. Deprived of freedom, girls become psychological wrecks. Watching them means seeing how they are coerced into doing things on a daily basis as if this is something as normal as making your bed in the morning. Prostitution is devastating. Some think the victims can be rehabilitated but that’s just another stereotype. The more time people spend in conditions of slavery, physical and mental abuse and coercive labour, the more difficult it is for them to return to normal lives.

UW: Could you expand on human trafficking and sexual slavery crimes?

Slave trafficking from one country to another is an intricate system built on corruption, stigma, embarrassment, fear and abuse. Unfortunately, most people have no idea how much psychological damage this causes in societies. The system is designed to make the victims look like dirty laundry repulsive to anyone. A related problem is the lack of accountability in NGOs and funds dealing with the issue, and there is plenty of corruption there too, just like in border patrols and other authorities in victim destination countries. They all want to wash their hands, just get rid of the victims and send them home. But the saddest part is that this is not the end. The women coerced into the sex industry are often killed, found dead at landfills or in uninhabited areas, and a week later five or six more women end up as sex slaves in the countries where brothels are in high demand.

UW: NGOs helping the victims of human trafficking to rehabilitate and return to social life receive significant international funding. However, reports of non-transparent allocation of funds are frequent, signalling possible corruption. What is the scale of corruption in reality?

NGOs dealing with the victims have certain agendas for the funding. The figures they report that we as journalists rely on are often exaggerated. Yet, the more we mention them in our articles, the more funding they receive. And reports of 20,000 women sold into slavery will get them more feedback than reports of 10,000. However, no one really checks the statistics. If worse comes to worst, they may be asked how many cities their figures cover. I want to give you an example of an NGO involved in fundraising from the US, Sweden, Norway and other countries that dedicate a lot of efforts to the anti-human trafficking campaign. I was once invited to a reception at the NGO president’s house. He had heated floors, 30 people waiting on us and drivers taking the guests home. Just think about how much that party cost. The contrast to what I saw at the NGO’s shelter centres was striking. They looked underfunded; the women lived in really poor conditions, while the man running the NGO was throwing costly and extravagant parties.

READ ALSO: Dark Matter

UW: An investigation like your Price of Sex typically draws a lot of attention and often leads to repercussions, including criminal prosecution. What was the reaction to the film in different countries?

Very different. The reaction in Washington where we presented the film after London really surprised me. People from the US State Department came to the screening; they wanted to talk to me. One woman I had talked to earlier about getting approval from US embassies to show the film all over the world told me that it had helped them to change laws regarding human trafficking and slavery in Greece. So, something did change. What matters to me is not just to make the film, but to reach out to decision makers who can change a given country’s policies on human rights, including human trafficking. Another important issue is to change social stereotypes and attitudes toward human trafficking and sexual exploitation. I am presenting my film in Eastern Europe, including Ukraine, to help people get over the social stigma surrounding sexual slavery. Another important objective is to reveal corruption, one of the most difficult issues for a journalist to report on. I’m doing my best to show people as much as possible about how the system operates and raise public awareness on related issues. My number one priority is to change the way people perceive the problem.

UW: The issue of sexual slavery you cover is shocking. What is your preferred target audience? Should it be policy makers, civil activists, or the general public in order to achieve the greatest results with this investigation?

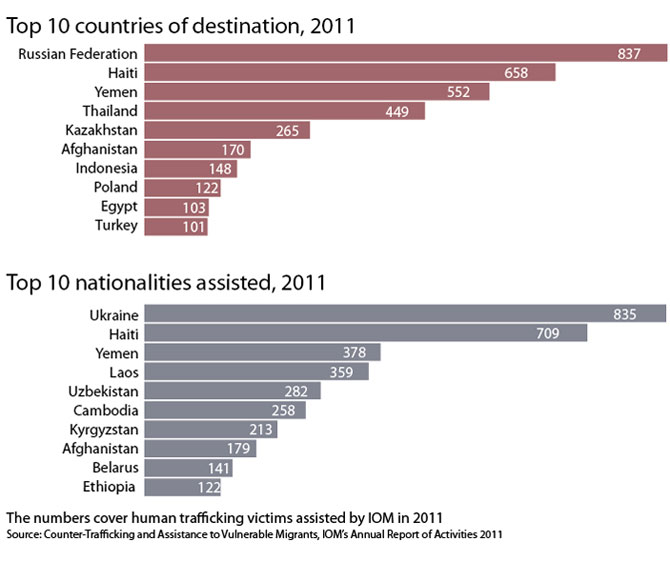

Apart from Eastern European countries as suppliers of slaves, destination countries should see it, too. I mentioned earlier that Greece was among the first destination countries to admit responsibility and take at least some steps to solve the issues of sexual exploitation and slave trafficking. Two other countries that The Price of Sex focuses on are Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. Unfortunately, I’ve been put on the black list in the UAE and my film was even banned from the relevant festivals there. I failed to show it at the annual Human Rights Film Festival in Abu Dhabi, too, and I faced the same attitude in Turkey. My film did not get into a single festival or special screening there.

UKRAINIAN SLAVES FOR EXPORT

According to estimates by the International Organization for Migration, over 120,000 Ukrainian men, women, and children have been victims of human trafficking since 1991. This makes Ukraine one of the leading suppliers in Eastern Europe, yet it is used as a transit or destination country more and more often in recent years. Domestic human trafficking has also been increasing as the victims are coerced into prostitution, farming, begging and other labour. The number of foreigners as victims has grown, too. The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court qualifies human trafficking as a crime against humanity. Ukraine ratified the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons Especially Women and Children, supplementing the Convention. This was followed by the ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings in 2011. Ukraine’s laws define human trafficking as a grave crime. According to Art. 149 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code, the penalty for human trafficking-related crimes carries a jail sentence of 3 to 15 years (see The Invisible Problem). On September 20, 2011, the Verkhovna Rada passed the Law on Counteraction of Human Trafficking. In 2012, a series of laws was passed to set up a comprehensive public system of interaction and assistance involving government authorities, NGOs and international organizations.

BIO

Mimi (Miroslava) Chakarova is a photographer and documentary filmmaker with experience in military conflict zones. For 10 years, Chakarova has been lecturing at the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. She is the recipient of the 2003 Dorothea Lange Fellowship for outstanding work in documentary photography. In 2005, she received the Magnum Photos Inge Morath Award for her documentary photography focusing on slave trafficking in Eastern Europe. Chakarova has directed several documentary films, including Tread Softly: Kashmir and The Price of Sex.