Most migrant workers are people who have shed their soviet paternalist illusions about any possibility that the state, or any other organization, is able to solve their problems and realized that they should build their own lives. A comment on a migrant forum says: “It’s better to show your child that parents want to gain something in life and work should be paid and appreciated better than it is here (in Ukraine – ed.)! Surviving on subsidies and raising a kid as a miserable person with a slave mentality is the easiest way.” People go abroad because they have no way to support their families with the salaries offered at home; education is uncompetitive in their homeland and gives no foundation for successful self-expression; they cannot accumulate initial capital to start their own business; and there is no well-paid demand for professionals, which makes personal fulfilment next to impossible.

In one way or another, all these factors stem from the tycoon-controlled model of Ukraine’s economy where oligarchs and the government closely tied to them are interested in keeping the labour force cheap and prefer to develop export-oriented raw material industries, such as steelworks, the chemical industry and lately to a greater extent, farming.

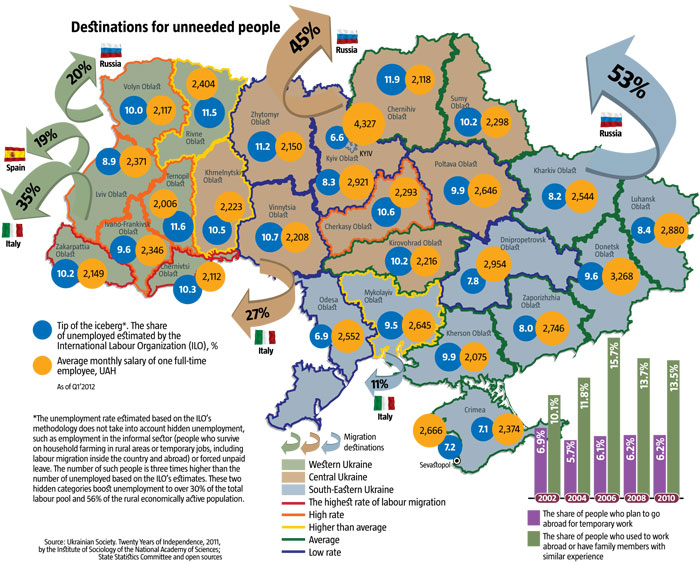

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), people employed in the informal sector such as household farming or seasonal work, as well as those on unpaid leave, Ukraine has nearly 6.6mn unemployed, including people emlpoyed in the informal sector such as houshold farming or seasonal work, as well as those on unpain leave, which is 30% of all the economically active population in the country and over 56% of that in rural areas. With the addition of the 0.9mn people forced to work part-time, unemployment hits 7.5mn. For most of them, as well as some of those who work full-time, yet have monthly wages that are close to minimum, their formal ‘employment’ does not fulfil its key function. They cannot support their family. As a result, nearly 1/3 of the Ukrainian population, rather than 2-2.5% by official statistics or 8-9% according to the ILO, have no work that can keep them above the brink of poverty. This pushes Ukrainians to go abroad to work en masse.

Under the current tycoon-controlled economic model, 13-15mn people, including families of people who have no decent earnings, are essentially unneeded in Ukraine. This is because the servicing of export-oriented raw material monopolies does not take much human labour and remains cheap. Any development of new industries might offer better salaries yet it is blocked by the ruling oligarchs and the government that depends on them. Both parties simply prefer this status quo to any other. As to the government, it prefers it this way because millions are forced to seek employment in the public sector where salaries are way lower than the real subsistence level.

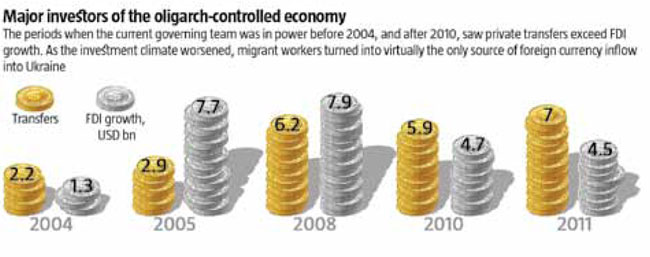

In 2011, private money transfers from abroad exceeded USD 7bn, or 4.3% of GDP. This was much higher than the growth of FDI which was only USD 4.55bn over the same year. Interestingly, the periods when the current governing team was in power before 2004, and after 2010, saw private transfers exceed FDI growth. As the investment climate worsened, migrant workers turned into virtually the only source of foreign currency inflow into Ukraine. In reality, their true contribution to the support of the state’s finances could be much more significant.

HIDDEN BILLIONS

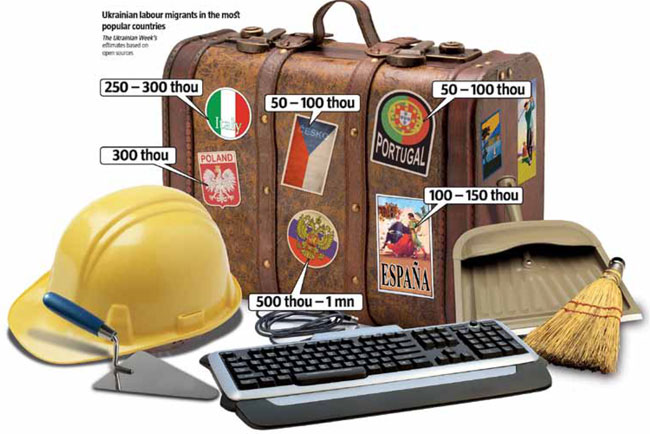

The most popular destinations for Ukrainian migrants in the EU include Poland, Czech Republic, Italy, Spain and Portugal. France, Benelux countries or Northern Europe are less popular while South-Eastern Europe, except for Greece, is hardly of any interest at all. Germany, the biggest and so far the most stable economy, is also no longer a priority destination as a result of its proactive campaign against illegal migrants.

Based on open sources and conversations with migrant workers, The Ukrainian Week has found that average migrant workers with families still in Ukraine, except for those who go to do seasonal work for two to three months a year, typically try to transfer an average of EUR 4,000-6,000 back home annually. Those who have no family or have their family with them abroad often do not transfer anything or a mere EUR 1,000 per year. People who go for seasonal work abroad usually save up to EUR 2,000-3,000 over three or four months and also bring it back home.

Counting exactly how many Ukrainians are working abroad is a challenge. Estimated numbers can range from 4.5 to 7mn people. In 2008, Caritas International estimated the number of Ukrainian migrant workers in the EU at 1.7mn and 2mn in Russia. In fact, however, all these numbers are often overestimated. Perhaps, they include Ukrainians who work abroad at present and those who have worked abroad in the past. According to the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Sociology, only 13.5% of those polled in 2010 said some of their family members had worked abroad and this number peaked in 2006 at 15.7%. The total number of households in Ukraine is approximately 16.6mn.

It is known, however, that labour migration has been massive in rural Western Ukraine. Estimates there show that more than 10-15% or 0.6-0.9mn of the local economically active population work abroad. With a similar number in Central Ukraine, except Kyiv and its suburbs, it has fewer labour migrants who travel to work abroad rather than move to Kyiv to work. Thus, from 0.9 to 1.3mn people from Central and Western Ukraine work abroad on a permanent basis. Despite high numbers of labour migrants in some depressed areas of South-Eastern Ukraine, Russia being the most popular destination for them, labour migration is less widespread there compared to other parts of Ukraine.

Thus, the total number of migrant workers who permanently work abroad is currently estimated at up to 1.4-1.8mn people.

FOREIGNERS AMONG HOMEBOYS

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), most Ukrainian migrant workers abroad are employed in construction (54%), housekeeping and caretaking for children and old people (17%), agriculture and trade (9% each) and industry (6%). This structure of employment made them particularly vulnerable to the crisis trends the EU has been experiencing. Ukrainian labour migration to Portugal, one of the most migrant-friendly EU member-states, peaked on the break of the 1990s and 2000s, but almost halved by 2009, going down from 70,000 to 38,000 according to official data.

A similar scenario occurred in Spain where most Ukrainians looked for work in construction which had been developing rapidly before the 2008 crisis, yet plunged to almost the lowest in Europe after it. Clearly, not all Ukrainians left the Pyrenees but the Ukrainian labour migrant community there shrank considerably. Recession caused the same process in Greece.

The gap between nominal salaries in Ukraine and Western Europe has shrunk over the past decade. As a result, fewer people feel the need to go abroad in search of a well-paid job, while some migrant workers have returned home for one reason or another. An average monthly salary in Ukraine in 2000 was USD 43 and that has gone up to USD 350 today. It has not become much easier to survive on that money in Ukraine because prices, especially for food, good education and accommodation have also escalated. Meanwhile, the purchasing capacity of salaries paid abroad has shrunk greatly. What had cost one euro in Ukraine in the early 2000s is often at least EUR 5-10 now, yet nominal earnings of migrant workers in the EU have not increased that significantly. Thus, some of them who have returned home see no sense in going back, while young people know the cost of life in Ukraine and prefer migration for permanent residence to developed countries as the income/price ratio is much better in Europe compared to Ukraine.

Experts observe that migrant workers who return home from the West go through strong emotional stress caused by the sharp contrast between their life abroad and at home, as well as the low level of culture in Ukraine. They are appalled by the way the government in Ukraine treats its people after having been treated with more respect in the EU, and by the disproportionate salary/price ratio here. Actually, they once again encounter all the factors that had once encouraged them to leave the country. As a result, most of them eventually start searching for work abroad again.

NEGLECTED POTENTIAL

In reality, the partnership of the state and one-time migrant workers should be one of the drivers of Ukraine’s modernization and European integration. Migrant workers nearly always return home with some benefits, such as knowledge of foreign languages and market psychology, self-reliance and contacts in Western countries, familiarity with European culture, including business, and many other things. If provided with the proper business environment and incentives from the state, they could invest the money earned abroad into their own small businesses at home.

For this, the government needs to unblock and facilitate Ukraine’s European integration, as well as ratify the Association Agreement and seal agreements to legalize Ukrainian migrants with European states where they work. It should create a comfortable environment for these people to come home to. In the first place, this includes the simple legalization of funds earned abroad and advice on investment options for former migrant workers. Today, many of them literally dig their money into the ground building huge houses – currently the key investment for Ukrainian migrant workers – which will be extremely costly to maintain after the government cancels subsidies for utilities and gas and electricity rates go up. As a result, they are unlikely to live in their mansions.

Migrant workers should be encouraged to invest their earnings into their own businesses with low interest loans worth, for instance, 1:1 to the amount of the earnings invested. The regions that are the major suppliers of migrant workers to European markets should be allowed to temporarily exempt all new businesses from taxes.

Meanwhile, the government is largely trying to fill the budget deficit caused by abuse of public funds through public procurements, the reluctance to stop tax evasion by Ukrainian oligarchs and big business, and the obvious and hidden subsidizing of industries or enterprises they control.

Authorities expect migrant workers to voluntarily report and pay flat tax and contributions to the Pension Fund which will cost them several hundred Euros a year, eating up a large chunk of their transfers home. No wonder that only 614 people volunteered to contribute to mandatory state pension insurance in June 2012, according to Maria Plaksiy, Head of the Pension Fund’s International Cooperation Department.

Meanwhile, the most powerful oligarchs seem to be quite cynical about this. “I think it will all come once we have accomplished the main thing…” said Dmytro Firtash, President of the Employers’ Federation of Ukraine, at its meeting on March 27th in Lviv. “It’s important to prevent things like MMM[1] in Ukraine where a man worked hard all his life, earned USD 15,000, returned to Ukraine, invested it – and lost it all. We should create the proper environment here.” However, the problem is that people have no trust in this government. Its approach to small and medium-sized business only makes it more distant from civilized standards.

Even private investors from the EU are cautious about investing in Ukraine as they fear that their embassies will fail to protect their interests. In that case, how can Ukrainian migrant workers, who have no protection from whatever the government may prefer to do to them, risk investing all their earnings into a business in Ukraine? Obviously, Ukraine’s huge investment and modernization potential can open through cooperation of the authorities and migrant workers only when the current government is replaced by a new one interested in Ukraine’s real integration with the EU and the import of European business and legal practice into Ukraine. When that happens, most Ukrainians who now work abroad will have a chance to play a significant role in the process.

[1] MMM was one of the largest Russian Ponzi schemes of the 1990s organized by Sergei Mavrodi